The CB500 was a good looker from any angle.

Straddle a Honda CB750 today and it seems like a nice compact package, certainly not overly large by current standards. Yet when it was released in 1969, the media applied descriptions like “huge”, “bulky”, “massive” and “formidable”. And compared to the comparable tackle of the day – British twins, BMWs and the like, the CB750 probably was a bit on the porky side – wider at least than we were used to. It made no difference to sales, as the CB750 went out dealers’ doors by the truckload, but Honda listened to the few detractors and came up with an almost immediate solution – the CB500.

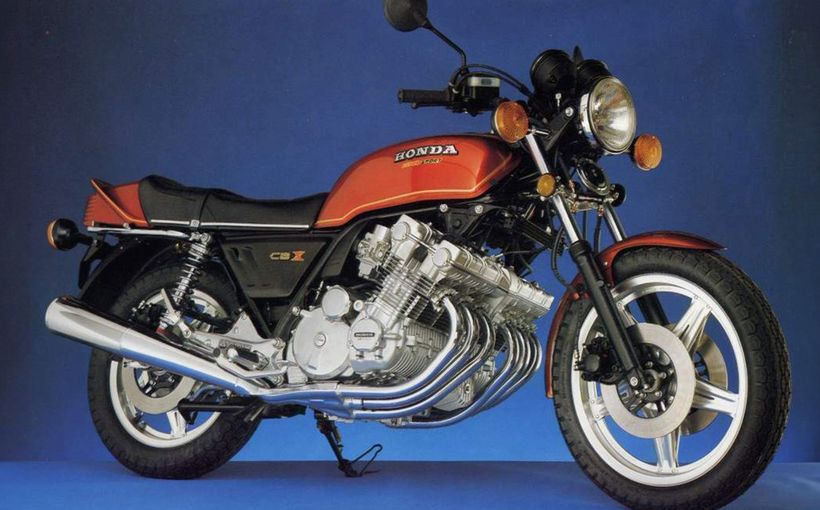

The Big H already had a 500-class contender in the DOHC CB450 twin, which was more than capable of staying with its Caucasian rivals, but the world wanted four cylinders, nothing less. Rather than produce a scaled-down, and thus overweight CB750, Honda started with a clean sheet of paper. Of course, the refinements that had made the CB750 such a hit were all there: a 100% reliable electric starter, disc front brake, powerful lights, big turn signals and superb finish, but one important thing was missing – weight. At 194 kg, the CB500 was over 50 kg lighter than the 750, and it felt it.

Outwardly straightforward, the CB500 engine was all-new and inside it contained some innovative features. With almost vertically mounted cylinders rather than the forward-inclined cylinders of big brother, the 500 had a more pedestrian look about it. Four 22mm Keihin carburettors controlled by a single cross shaft removed some of the bugbears of the original CB750 multi-cable set up, although a common complaint was that the return spring was overly strong and made prolonged full throttle riding a chore. Nevertheless, the system made carburettor synchronisation decidedly easier.

Honda had set out to make the 500 a quieter engine than the 750, and one change was to replace the 750s front cam chain roller with a rubber slipper cradle. A relatively high 9:1 compression ratio was achieved with shallow combustion chambers in the two-valve head and fairly flat-topped pistons, resulting in a cleaner burn and lower exhaust emission levels – an issue that was beginning to raise its head in the US market. Downstairs, the five-main bearing crankshaft assembly mirrored that of the 750, with the two outer throws at 180-degrees to the two inner. An alternator hung from the left end of the crankshaft, with twin contact breaker points on the right. To connect the crankshaft to the five-speed transmission, a Morse chain driven by tiny sprockets with rectangular teeth set in rows of six and five provided an almost silent assembly with high load carrying characteristics. Inside the sprocket on the gearbox end, rubber shock absorbers further smoothed out the engine’s firing loads. A major variation from the 750 was the employment of a wet sump instead of a separate oil tank, which was claimed to keep the oil cooler and eliminated the external oil lines of its big brother. At a quoted 50 bhp at 9,000 rpm, the CB500 was, on paper at least, no rocket ship, but it was a willing revver and when stoked, covered the ground quite quickly.

With all the attention to detail in the transmission, the CB500’s gearbox is not exactly the smoothest to come out of Japan. Down changes, particularly when pressing on a bit, were stiff and clunky, with a very solid pedal action. The clutch too, would slip when pushed hard.

The oversquare (56.0mm x 50.6mm) dimensions kept the overall engine height low compared to the 61 x 63 750, meaning that the cylinder head could be removed with the engine still in the frame. This proved rather handy, because as CB500s racked up a few miles they tended to weep oil from between the head and cylinder block. The cure, facing both surfaces, was relatively straightforward, and sometimes had to be performed under warranty, so not having to remove the entire engine/transmission unit was a blessing. Another thing that showed up after a bit of use was the tendency for the mufflers to rust out around the rather ornate fluted ends and where the small balance pipe linked the two ‘trumpets’. It created a flourishing turnover in after-market, usually four-into-one, exhaust systems, which in turn has made original pipes in good condition rare and expensive for restorations.

When new, the front disc brake, which at 260mm was 20mm smaller than the 750, worked very well, but as time went on its efficiency seemed to dissipate due to the combination of the stainless steel rotor and the pad compound. The rear drum, sourced from the CB450, was an excellent fade-free unit, which was just as well, as it was called upon to do quite a bit of work.

Just like on the CB750, the standard CB500 handlebars were generally considered to be too high, and dealers did a roaring trade in swapping these for the genuine Honda ‘touring bars’ which looked like the traditional British one-inch rise style. This modification also required fitting a shorter clutch and throttle cable, and preferably a shorter top hydraulic hose to the master cylinder. It did however, transform the riding position and hence, comfort of the CB500 as a tourer as the rider no longer had to sit bolt upright and exposed to the wind. The wide, flat seat was well padded and comfortable for rider and passenger alike.

The chassis package is something Honda definitely got right on the CB500, which could be flicked around effortlessly, thanks partially to the 55.3 inch wheelbase – 2 inches shorter than the 750. The all-new front fork had well chosen spring and damping characteristics and the rear shocks coped well, at least when new. Once again, a few miles on the clock seemed to prematurely age the rear end. Winding the springs up to the maximum preload worked for a while, but a set of Koni shocks was the real answer. The biggest difficult was in carrying a pillion passenger, when the rear shocks would bottom repeatedly. The sweet handling was undoubtedly mainly due to the frame geometry and stiffness, although the swinging arm, fabricated from two pressings and welded together, was no lightweight item.

For those who had graduated from British tackle, the standard of refinement on the CB500 was sublime. Each of the big instruments emitted a soft glow at night, while a panel of four different coloured lights indicated turn signals, oil pressure, neutral and high-beam.

Honda tantalised the world with a sneak preview of the new CB500 at the San Diego Motorcycle Show in April 1971. In Australia, the first CB500s arrived around September, just in time for the second running of the Castrol Six Hour Race at Amaroo Park.

Although not touted as a sports machine in the 500cc class that contained rapid two strokes from Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki, the Honda had a big advantage in fuel consumption – around 50 mpg even when pushed hard. Four CB500s entered the race, finishing first and second in the 500cc class.

The CB500 stayed in production for four years and sold well, particularly in the UK. Itv was replaced by the CB550; basically an identical motorcycle with capacity incred to 544cc by increasing the cylinder bore from 56mm to 58.5 mm. This gave slightly more torque,; a feature demanded by the all-powerful US market, which finally got what it really wanted with the introduction of the 626cc CB650 in 1979.

Protect your Honda. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.