The motorcycle you see here can lay claim to being the one of the most significant bikes ever produced. When the CB750 Honda first appeared in significant numbers in 1969 it drew – at first – shock, amazement, suspicion and scepticism. But all of this disappeared almost immediately the road tests started to roll out, as journalists the world over salivated and scrabbled for new superlatives. It was that good. In Australia, the very first CB750 to arrive did not even hit the street – it was air-freighted in and dismantled by owner Jack Walters to provide the motive power for Victorian ace Lindsay Urquhart’s latest racing sidecar. And very successfully too – it won first time out at Phillip Island on New Year’s Day 1970, and again at Bathurst at Easter.

The original model CB750 is these days, often erroneously referred to as the ‘KO’ model. K stands for the Japanese word ‘kairyo’ which means updated or improved. The second model, released in 1971, became the K1, or the first improvement of the original CB750. As soon as CB750s began to appear, they were an instant status symbol. No-one could miss the four cylinders and four separate exhausts. Everyone who rode a CB750 knew they had something very special. Winning the big race at Daytona in early 1970 went a huge way towards putting the CB750 on the map. The all-new bike had beaten the bigger line-up from BSA-Triumph and Norton to prove its performance at one of the world’s most influential events.

Not that the CB750 was without its faults. When ridden hard, the rear chain could cry enough, and once separated, fire itself into the left side crankcase. Nasty. Fortunately rear chain technology was accelerating as well to cope with the new wave of super bikes that included the GT750 Suzuki and the Z1 Kawasaki. The original single cable throttle required a gorilla grip to operate the twistgrip. This was quickly corrected on the K1 which used twin cables operating on a barrel roller to lift the carburettor slides. Balancing the carbs was vital for a sweet running motor and only an expensive 4 vacuum gauge set-up kept everything right. Exhausts rusted and needed frequent replacement, especially when used daily around the city. The after-market sprang into action with locally made and imported four-into-one pipes which were cheaper and louder. Rear tyres also had a fairly brief existence if pushed hard. Rear shocks were not great to start with and did not improve with age. The Dutch Koni company made a killing in the after-shock market. Inside the engine, the silent-when-new cam chain (and primary chains) soon began to make itself heard, but was often ignored at the owner’s peril. Front forks began to leak oil but new seals were relatively cheap.

Primary chain inevitably became a little rattly but was usually ignored. The bottom end of the engine, however, was as strong as an ox, and as big-bore kits and other performance enhancing gear became available, the standard crank showed that it could handle vast increases in horsepower.

It did Honda CB750 sales no harm at all when Bryan Hindle and Clive Knight took out the second running of the Castrol Six Hour Race in October 1971. Sales of the K1 skyrocketed and continued with the introduction of the K2 in 1973. In Australia, the K2 stayed with us for nearly four years – we skipped subsequent model with their very minor styling changes until the K6 version. However it’s fair to say that the Honda may have sat on their laurels for too long. When the Kawasaki Z1 hit the market in 1973, the CB750 started to look its age. Not long after, Suzuki came out with their own ‘four’ – the Z1-inspired GS750 and later 850. Only Yamaha dallied with the concept of a ‘four’, opting for the unloved XS750 triple buy finally acquiescing with the XS1100.

Honda even gained extra life from the original design with an automatic transmission version. For three years, Honda persevered with the 750 Hondamatic, but the public failed to embrace the concept. The 1976 model shown has covered just 19,000 miles from new. Later versions used a four-into-two exhaust system, while the 1976 model used a visually similar four-into-one system to that employed on the CB750 F1. The cylinder head was reworked with smaller valves to increase torque, and the two-speed automatic transmission was derived from the unit used in the Honda Civic sedan.

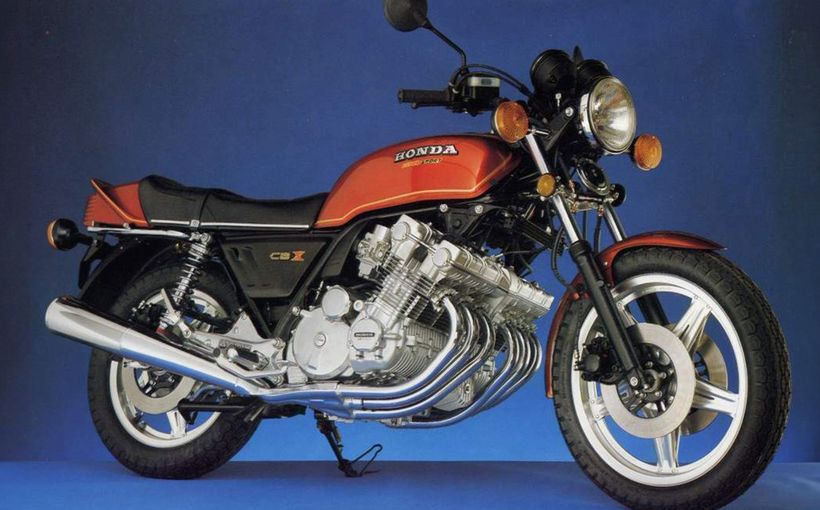

But Honda was not ready to ditch its single overhead cam model just yet, and decided that a major styling change was sufficient to regain lost market share. It wasn’t. The revamped model, called the F1 and later the F2, was a sales flop, although they were undoubtedly fine motorcycles. With a standard 4-into1 exhaust system (admittedly a muted and rather choked one) rear disc brake and racy styling, the F1/.2 looked good but failed on the showroom floor. It was time to bite the bullet, and the all-new 4-valve DOHC CB750F and CB900F was the answer – brilliant, fast and handsome motorcycles.

Life for the CB750 has come a full circle in the past 47 years, and the model is now one of the most collectable motorcycles on the planet. As vintage Japanese rallies continue to soar in popularity, riders are discovering that the CB750 is all anyone could want – reliable, good looking, comfortable and with plenty of poke. This retro market is fuelled by companies around the world that can supply virtually anything – including the once rejected four separate exhaust pipes. Yamiya, based in Nagoya, Japan, has a thriving business supplying an increasing range of CB750 parts – not just pipes but fuel tanks, plastic side covers, badges, mudguards, seats, headlight shells and chain guards.

There wasn’t much wrong with the CB750 when it shock the world way back in ’69, and with this is one motorcycle that has certainly aged very well.