Datsun/Nissan Z cars: How Japan redefined the American sports car

“The Z was designed for America. It was based on the formula of the traditional British sports cars that had done so well in the USA, but with the important difference of a modern coupe body and such civilised features as wind-up windows and an effective heater,” noted The Z-Series Datsuns author Ray Hutton when describing the impact of the original 240Z launched in 1970.

“Its E-type looks at a bargain price soon established it as the best-selling sports car of all time. It took the Chevrolet Corvette 25 years to sell half a million; the Z sold 500,000 in less than a decade.”

Japan’s Nissan Motor Company, established in 1933, wasn’t exactly new to designing sports cars when the 240Z took centre stage. Indeed, from the early 1960s under its Datsun export brand, Nissan had followed iconic British manufacturers like MG, Triumph, Jaguar and Austin-Healey in creating open-top sports cars under the Fairlady name that appealed to North American tastes.

Hutton: “This was the era of the MGA, the TR3A and the Healey 100 Six. Nissan wanted to compete squarely with the British – to offer an open sports car at a reasonable price – and now they had learnt how to do it, using high volume production components in a different package: the very same formula that produced the British sports cars that the Americans loved.”

By 1969 Nissan was the world’s seventh largest car manufacturer, with an excellent understanding of US buyers and the potential for much greater sales in the world’s largest and most lucrative car market. Its Datsun brand was well-established on a global scale with annual exports exceeding 300,000 units. The time was ripe to redefine the American sports car.

Image: Nissan

Datsun 240Z, 260Z and 280Z (1970-1978)

The 240Z (model code S30) dazzled on debut in its target market in late 1969 as a 1970 model. Americans were instantly seduced by its stylish and elegant supercar lines and, thanks to use of numerous shared parts to minimise costs, it came with irresistible pricing.

The motoring press reaction was effusive with Road and Track calling it “the most exciting GT car in a decade” while Car and Driver claimed “the difference between the 240Z and your everyday 3,500-dollar sports car is that about twice as much thinking went into the Datsun.”

Despite long waiting lists, 240Z sales in the US topped a staggering 50,000 units by 1971 and were destined to double the following year with increased production. It was also sold in other LHD and RHD markets including Australia, where it was greeted with similar enthusiasm if not sales volume given our comparatively small population. In Japan it was sold as the Fairlady Z with smaller 2.0 litre engines.

Although it appeared to mirror the Jaguar E-type in configuration, its key dimensions were close to those of the Porsche 911, which was no surprise given the strong influences of both cars in establishing the initial concept under US-based German design consultant Albrecht Goertz. There was plenty of room inside for large Americans, which Goertz had insisted on to ensure its success. And the sloping hatchback gave full access to a generous luggage area.

Within its compact 91-inch/2305mm wheelbase and unitary construction, there was close to perfect 50:50 weight distribution. The light 1044kg kerb weight was also impressive given its iron-block six cylinder engine and other typically robust engineering which by then was a Datsun hallmark.

Image: https://en.wheelsage.org/

The 240Z also offered unusually high ground clearance, which with its independent suspension made it capable of tackling poor road conditions with great composure and comfort. As a result, it was ideal for rallying, as proven by multiple victories in the gruelling East African Safari. Its streamlined appearance, though, flattered to deceive with a less than stellar 0.467 drag co-efficient. Not that aero efficiency mattered much back then.

The L24 2.4 litre (2392cc) SOHC inline six was derived from the Datsun 1600’s (aka 510) L16 four, sharing the same oversquare bore and stroke dimensions and numerous components. It comprised a beefy cast-iron cylinder block, forged steel crankshaft with seven main-bearings and a 12-valve aluminium head fed by twin SU/Hitachi 46mm side-draughts. It could spin safely to 7000rpm but that was unnecessary given that SAE gross figures claimed 151bhp (113kW) at 5600rpm and 146ft/lbs (198Nm) at 4400rpm.

Depending on the country of sale, the 240Z was produced with both four-speed (US) and five-speed gearboxes. Again, these were derivates of the 1600/510 units but with different ratios and greater strength to cope with the L24’s extra torque. From 1971 a three-speed automatic option was added.

MacPherson strut front suspension was shared with the Laurel 1800 sedan. The rear also used struts but they were connected to wide-based wishbones unique to the 240Z. There was also rack and pinion steering, front disc brakes and finned alloy rear drums (shared with the 2000 Sports) inside 14-inch steel wheels.

Image: https://www.motortrend.com/

UK Autocar’s test of a standard five-speed 240Z in 1971 clocked 0-100km/h in eight seconds which was slightly quicker than a contemporary Porsche 911 and superior to most other segment rivals. It also covered the standing quarter in 15.8 seconds with a top speed of 125mph (200km/h).

Handling was judged to be on the understeering side of neutral with excellent cornering ability by 1971 standards. It also had more than enough torque to break rear traction if desired, which was a response appreciated by rally drivers of the era.

In an Autocar comparison between the 240Z and an Alfa Romeo 2000 GTV, Hutton found that “given equal drivers, the Alfa could not stay with the Datsun over ordinary British B-roads, despite the Italian car’s delightful, subtle handling.”

When sales ceased at the end of 1973, after four years in showrooms, more than 190,000 240Zs had been produced - 135,000 of those, or more than 70 per cent, were sold in the US.

Datsun 260Z

The 260Z launched in 1974 brought an engine displacement increase to 2.6 litres (2565cc) by way of a slightly longer stroke. To appeal to a wider audience, it also offered a choice of existing two-seater or a new 2+2 configuration.

The 2+2 was the same as its stablemate from the nose to the windscreen but a substantial 300mm was added to the wheelbase behind it, with a corresponding increase in overall length featuring restyled roof, doors and rear bodywork. Road testers reported slight improvements in ride quality and directional stability due to the longer wheelbase.

A stronger chassis and extra equipment raised the two-seater’s kerb weight to around 1100kg with the new 2+2 nudging 1200kg. That made the 2+2 more than 150kg heavier than the original 240Z and US-delivered models became even heavier in 1974 when 5mph impact-absorbing bumper bars were mandated.

Based on SAE gross figures, the 260Z’s L26 engine increased outputs to 121kW/213Nm. However, car manufacturers were starting to use less flattering but more relevant SAE or DIN net figures, measured with all engine equipment attached. So, even though the 260Z had higher outputs in gross terms, both dropped dramatically under net measurement to only 104kW/186Nm.

Image: Nissan

With its slightly longer stroke, the 260Z didn’t rev as freely as the 240Z, with road testers noting valve bounce at 6800rpm (the 240Z would rev cleanly to 7000rpm). Gear ratios were also revised and the final drive was lengthened from 3.9 to 3.7:1.

As a result, the 260Z’s extra power and torque could not overcome its weight gain and longer gearing. Compared to the 240Z, Autocar’s test of a 260Z two-seater resulted in an eight km/h drop in top speed (192 km/h), 0-100km/h in 9.9 secs which was almost two seconds slower and its 17.3 secs standing quarter was almost 1.5 secs slower.

US models increasingly choked by anti-smog equipment were hobbled even more. Even so, in its first year on sale in the US in 1974, the 260Z achieved an excellent 50,000 sales of which almost 20 per cent were 2+2s. That percentage would grow to 30 per cent.

However, Nissan knew it would need to again increase the engine’s displacement to maintain adequate performance in the US. Indeed, the decision to raise it to 2.6 litres was primarily to overcome power losses caused by North America's tough anti-smog mandates. As a result, the 260Z was only on sale there for one year.

Image: Nissan

Datsun 280Z

The importance of the US market was evident in the 280Z replacing the 260Z in 1975. This model was unique to North America, with its L28 engine representing the second and final displacement increase of the L24 with a larger bore size yielding 2.8 litres (2753cc).

The 280Z was the first Datsun Z-car to be equipped with EFI which with revisions to valve sizes, combustion chambers and camshaft profiles resulted in higher outputs of 111kW/221Nm with improved smoothness.

Fortunately, the Datsun 280Z was faster than the 260Z despite big weight increases caused by the heavy 5mph impact-absorbing bumpers, increased luxury features and (in California only) a huge catalytic converter. The heaviest 2+2 automatic 280Z now topped 1300kg, which was more than 250kg (or quarter of a tonne) heavier than the original 240Z!

“The original Z-car had redefined the sports car,” Hutton noted. “In less than a decade 550,000 had been sold, making it easily the most popular sports car in history. Though some enthusiasts were disappointed that its replacement was to be more ‘GT’ than ‘sports’, by 1978 Nissan had a good idea of what was needed to maintain and expand the Z’s market in the future. The world had changed since 1969 and the new car, the 280ZX, needed to reflect that.”

Image: Nissan

Datsun 280ZX (1978 to 1983)

The second generation Z-car (S130) launched in 1978 was widely seen as a facelift of the first, but the 280ZX was mostly a new car from the ground up. In fact, the only major hardware carried over was the engine and transmission.

Again available as either a two-seater or 2+2, the two-seater wheelbase was 15mm longer (2320mm) and the 2+2’s was 85mm shorter (2520mm) but overall lengths, widths and heights were similar to their predecessors.

With fuel economy increasingly important, the 280ZX was the first Z-car, indeed first Datsun, to include wind-tunnel testing in its design process. The 240Z’s 0.467 Cd was lowered to 0.385 and lift was slashed from 0.41 to just 0.14. Kerb weights were capped at 1200kg for the two-seater and 1292kg for the 2+2. It also had a lower centre of gravity and maintained the breed’s close to ideal 50:50 weight distribution.

The rear suspension’s unique lower wishbones were replaced by semi-trailing arms shared with other Nissan models to reduce production costs, but this design offered less desirable rear wheel geometry. The 280ZX also introduced four-wheel disc brakes (solid rear) and less steering effort with revised rack gearing.

Image: https://en.wheelsage.org/

The L28E engine, with the E denoting EFI, was similar to that used in the US-only 280Z producing 104kW/202Nm, with US-delivered cars having slightly lower outputs. Transmission choices were five-speed manual or three-speed auto.

Autocar’s test of 280ZX two-seater manual produced a 0-100km/h time almost identical to the 260Z at 9.8 seconds but top speed had dropped to 180km/h. The magazine noted: “It is capable of surprising cornering speeds for its size…being a comparatively long car it gives the driver very good feel of what is happening – this is a highly impressive aspect of the 280ZX which we greatly enjoyed.”

Other reviews were less complimentary, lamenting the Z-car’s evolution to a heavier and more luxurious GT. Even so, this was clearly what the all-important Americans wanted as a huge 78,000 units were sold there in the first year, with 75 per cent of those being two-seaters.

Image: Nissan

1980 saw a limited edition (3000 units) 10th Anniversary model released with special paint, leather trim and a new T-roof option, comprising removable smoked-glass panels on either side of a central spine. These panels were carried in vinyl pouches in the luggage area.

The first Z-car with forced induction arrived in 1981 – the two-seater 280ZX Turbo. Its L28ET engine was equipped with a Garrett T3 turbocharger with no intercooler, but the bonnet featured a large NACA duct to assist with controlling higher engine bay temperatures.

It produced a punchy if not lag-free 134kW/275Nm and at launch was available only with automatic, as Nissan was concerned the five-speed manual’s strength was marginal given the extra torque. Stiffer suspension and larger wheels and tyres were specified given the big performance increase.

The auto-equipped 280ZX Turbo was the fastest Japanese import on the US market at the time, with a 210km/h top speed, 0-100km/h in 7.4 secs and 16.6 secs standing quarter. A 2+2 Turbo variant and five-speed manual option came in 1982.

Image: Nissan

Nissan 300ZX (1984-1989)

When the 280ZX ceased production it was the best-selling Z model to that point, when the Datsun name was replaced globally by Nissan. However, given that the Z’s ageing inline six had reached its practical limits, the green light was given to develop a new V6 engine family (VG series) to power the equally new third generation 300ZX (Z31).

The result was a compact 3.0 litre (2960cc) EFI SOHC V6 with thin-wall cast iron block, aluminium heads, tough forged steel crankshaft and rods, two valves per cylinder and oversquare bore and stroke. It was shorter and lighter than the inline six it replaced, with a narrow 60 degrees V-angle ensuring it was also no wider than the L28 with ancillaries. And it was designed from the outset for both turbo and non-turbo applications.

Although the new 300ZX, in a choice of two-seater or 2+2, was identical to the 280ZX in wheelbase and lineball in other key dimensions, its striking new body style did not share one outer panel. Chassis and suspension hardware were largely carried over, but with numerous refinements including sharper steering feel and more precise handling.

The new body profile was more wedge-shaped, with the shorter V6 allowing greater slope and less aero drag in a nose that for the first time had rectangular and semi-retractable headlights. These changes along with a steeper windscreen rake contributed to a best-ever 0.30 drag co-efficient.

The new V6 outputs were far superior. The naturally aspirated VG30E 3.0L V6 produced 127kW/237Nm while the VG30ET version with Garrett T3 turbocharger pumped out 170kW/328Nm. Transmission choices were five-speed manual or four-speed auto and Turbo models had larger brakes and wider wheels and tyres, plus adjustable shocks offering a choice of three ride settings via a cockpit control.

The 300ZX Turbo was easily the fastest Z-car to that point, with Autocar claiming a 220km/h top speed and 0-100km/h in 7.2 secs. Motor claimed even faster figures of 225km/h and 6.8 secs which matched those of a contemporary Porsche 944. The Z-car now had a seat at the supercar table.

Nissan 300ZX (1990-2000)

Although it shared the same name, the second 300ZX (Z32) was the fourth generation of the Z-car, being one of the first production cars to introduce CAD software in creating another bold and more rounded styling evolution. It also introduced twin-turbo technology.

Wheelbases were longer with a 130mm stretch for the two-seater (2450mm) and 30mm increase for the 2+2 (2550mm). The new body was slightly shorter but wider along with considerable increases in kerb weights, with the two-seater now 1520kg and 2+2 1549kg.

In response to those big weight increases, there were more powerful variants of the 3.0 litre V6. The naturally aspirated and rev-happy VG30DE now had DOHC heads with four valves per cylinder and an early form of variable valve timing, producing 166kW/268Nm.

The VG30DETT grabbed headlines as the first twin-turbo model, with its Garrett turbochargers and dual intercoolers pumping 220kW/384Nm. These unprecedented outputs gave supercar performance with reports of 0-100km/h in under six seconds and a governed top speed of 250km/h. Turbo models were also equipped with new four-wheel steering under the name Super HICAS (High Capacity Actively Controlled Steering).

Road and Track claimed the 300ZX Turbo was “one of the ten best cars in the world’. It also won Motor Trend’s Import Car of the Year award in 1990 and was one of the magazine’s Top 10 performance cars, in the same year Nissan celebrated one million Z-car sales in North America since its launch three decades before.

All 300ZXs were now equipped with T-bar roofs and in 1993 came the first convertible. However, by then sales of imported luxury GTs, including its Toyota Supra nemesis, were in serious decline in the US due to unfavourable currency exchange rates and mass buyer migration to more practical SUVs and pick-ups. US sales of the 300ZX ended in 1996 with production continuing for other markets until 2000. The Z was dead – or so we thought.

Fifth generation: Nissan 350Z (2003-2009)

The appearance of several concept cars in the years following the Z’s demise created enough positive public reaction for Nissan to revive the breed in the new millennium. The emphasis on the fifth generation Z-car was returning to more of a hard-edged sports car than a luxury grand tourer in appealing to a younger demographic.

The 350Z (Z33) featured the signature long bonnet, short boot and sloping hatchback roof. There was also a roadster variant but no 2+2 for the first time since the 260Z. Its 2649mm wheelbase was almost 200mm longer than the 300ZX yet it was deceptively close in length, width and height with the wheels been pushed out to the corners under bulging wheel arches.

The 350Z’s wind tunnel-tuned styling maintained a low 0.30 Cd and extensive use of aluminium resulted in a significant drop in kerb weight of more than 70kg for the coupe (1446kg) but the roadster with its greater chassis reinforcement was about the same at 1563kg.

Front suspension featured double wishbones while the rear was a sophisticated multi-link arrangement, with both using forged aluminium components which greatly reduced unsprung weight. Brembo brakes were popular options.

Image: Nissan

The new all-aluminium VQ series V6 heralded non-turbo engines in reviving the spirit of the original 240Z. The DOHC 24-valve 3.5 litre (3498cc) VQ35DE packed 214kW/371Nm, which were much higher outputs than the 166kW/268Nm of the non-turbo 300ZX. Transmission choices were six-speed manual or five-speed automatic.

When released in the US as a 2003 model, the 350Z was available in five trim packages comprising 350Z (base), Enthusiast, Performance, Touring and Track offering different equipment and performance levels. These choices would expand to include Anniversary in 2005, Grand Touring in 2006 and hot NISMO variants in 2007.

In 2006 there was also a mid-cycle facelift and power output increased to 224kW. This stepped up again in 2007 with the VQ35HR (High Revolution) producing a definitive 228kW at a highest ever 6800rpm and 363Nm at 4800rpm.

The 350Z could do 0-100km/h in 5.7 secs with a 14.4 standing quarter and governed 250km/h top speed. Motoring writers praised the 350Z, particularly its outstanding performance at an affordable price (under USD $30K) which was consistent with the original 240Z’s value for money appeal.

According to Motor Trend “with a competent driver at the wheel and the traction control switched off, many Porsche Boxster drivers would be hard-pressed to post better lap times than the Z.” It also won numerous magazine awards including Road and Track’s 12 Best Cars under $30K, Car and Driver’s 10 Best Cars of 2003, Top Gear’s 2004 Car of the Year and many more.

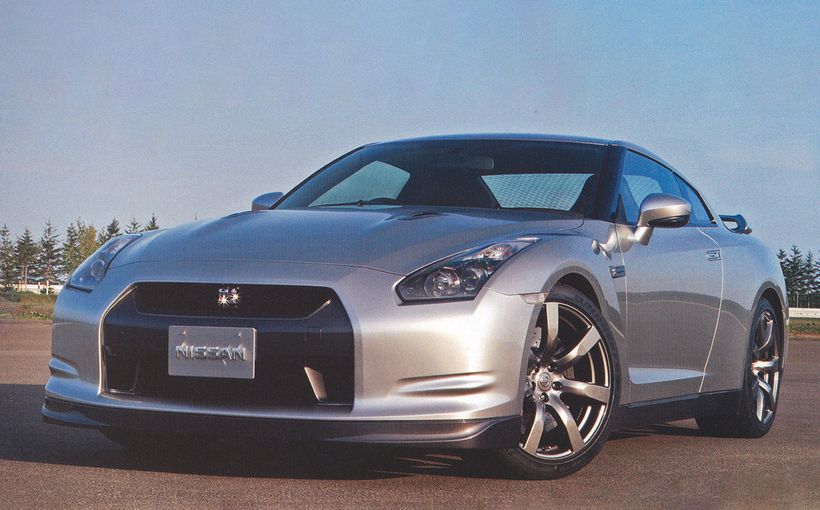

Nissan 370Z (2009-present)

Although the sixth generation Z-car looked similar to the previous model, it masked a significant redesign. The 370Z (Z34) had a 99mm reduction in wheelbase to 2550mm. It was also shorter, lower and wider with a broader rear track; the coupe and roadster having similar kerb weights to the 350Z versions.

The 370Z continued the Z’s non-turbo evolution with adoption of the larger 3.7 litre (3696cc) VQ37VHR V6, which was the first Nissan production engine equipped with VVEL (Variable Valve Event and Lift) that produced sharper throttle response and, combined with its longer stroke, superior torque at low rpm.

Proof of its rev-happy nature was a 7500rpm redline and its stomping 248kW being tapped at 7000rpm. Hotter NISMO variants offered 261kW at an even higher 7400rpm and 374Nm at 5200rpm. Transmission choices were six-speed manual or new seven-speed automatic with a manual-shift mode using paddle shifters.

With the seven-speed automatic, a 370Z coupe could clock 0-100km/h in a scant 4.6 secs and scorch the quarter mile in 13.3 secs at 170km/h. Like the 350Z, numerous special editions were released.

Image: Nissan

Nissan Z (2022)

After 13 years the long-awaited replacement for the venerable 370Z arrives in showrooms in 2022. The seventh generation (Z35) drops the breed’s traditional model-naming based on engine displacement and is called simply the Nissan Z.

With retro-inspired styling cues from previous models, it’s based on the same chassis platform as the 370Z but revised for sharper handling and equipped with an LSD and big brakes inside 19-inch wheels. It shares the same 2550mm wheelbase, is close in width and height but slightly longer overall.

The new Z also sees the return of forced induction, with the equally new VR30 3.0 litre twin-turbocharged V6 producing an unprecedented 298kW at 6400rpm and 475Nm of torque served at full strength across a staggeringly wide 4000rpm band between 1600-5600rpm. Transmission choices are six-speed manual or nine-speed automatic. This awesome combination should set new performance benchmarks!

The evolution of the Z-car, which now spans more than half a century, has gone full circle from two-seater sports car to luxurious grand tourer and back again. It is an icon of Japanese performance cars and an automotive Super Model by any measure.

Comments

carnut_73

G'day Fletch. Another awesome "Classic Restos" episode! You've got quite a collection of Mopars. My favourite have always been the 1962 through 1968 Imperials.

Motown1

Loved the episode so much I watched it twice. Great story well told and what an amazing car. A big job but well worth it. Imperial LeBaron by Chrysler - has a nice ring to it and gotta love those tail lights.

carnut_73

I agree. I love the fun and humour shown by the mechanics near the end of the video. I've never seen Fletch laugh so much. It made me laugh as well! :D

Blinkie1

Gee Fletch that was worth the wait my friend, cant wait for the second episode either. That Imperial sure looks like it will clean up okay too. The 440 wasn't to bad either when stripped down by the sound of things and giving more torque will be great down low with plenty of get up and go. Those guys doing the rebuild sound like awesome lads too.

Stay safe bro, thanks a heap.

Cheers

Blinkie1

carnut_73

What I love is the humour and fun these blokes seem to have. What good is working if you don't enjoy what you do and get to have a laugh from time to time? :)

Blinkie1

I couldn't agree with your more on that one carnut_73 as it is nail on the head and always been the way where I have worked over the years and there's been many.

Take care and stay safe bro.

Cheers

Blinkie1