BMW 7-Series: The driver’s choice among flagship luxury sedans

In the four and a half decades between the end of World War Two and 1990, just three times has one car clearly earned the title of best in the world. The most recent of these was the BMW 750i which made its debut at the Geneva Salon on 5 March 1987. Arguably, BMW had made the greatest recovery of any automotive manufacturer in the postwar period, having come close to bankruptcy during the 1950s; to out-manoeuvre Daimler-Benz in the über-luxury saloon stakes must have brought joy to many Bavarian souls!

By contrast, the manufacturers of the other two standout cars were almost predictable. Cadillac, the flagship marque of General Motors, surfed better and further on the immense wave of postwar prosperity than any rival. Its all-new 1948 model looked the goods with Harley Earl jet aircraft styling themes, but it would not be until the following season that Cadillac engineers would slip the brilliant new high-compression V8 slipped beneath that long bonnet. The Cadillac Series 62 outshone all rivals, setting a standard for other American manufacturers and beyond the reach of anything from Europe, although the Jaguar Mark VII was probably the most distinguished of these in terms of performance (from the magnificent twin overhead camshaft 3.4-litre six) and luxury for the money.

Fast forward to 1974 and Mercedes-Benz produced its super saloon 450SEL 6.9. There had been standout Mercedes since the 1920s and in the postwar era, some would suggest the 300SL ‘Gullwing’, 600 or 300SEL 6.3 could be claimants. But I exclude sports cars from this reckoning. As for the 600, it probably was the world’s finest car in 1963 but it occupied exclusive territory and sold in very low volumes. The 6.3 was a fabulous hotrod, but not a brilliant handler with its semi-trailing arm rear suspension. The 6.9 variant of the W116 S-Class offered no such compromise. At the time of its unveiling, BMW executives must have wondered how they could compete. The first 7-Series was nearing the end of its development process and was set for an international debut in 1977, but no V8 engine – let alone one displacing 6.9 litres! – was on the drawing board.

It was the BMW 1500 that had driven the company back from the brink in 1961. Arguably, there was more Borgward than Mercedes-Benz character to the zesty 1500, but BMW management had identified for itself a niche market, previously occupied by Borgward – and, remember, the pundits said ‘BMW’ stood for ‘Borgward Macht Weiter’ (Borgward comes again) – which could give Mercedes decision-makers a headache. If the 1500 represented a first step towards Mercedes territory, the E3 New Six launched in 1968 was a more definite one.

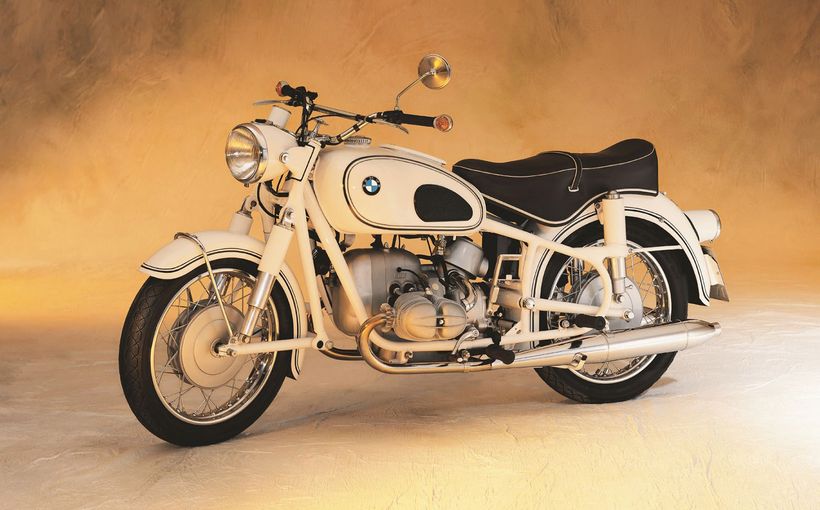

Image: https://en.wheelsage.org/

BMW’s product planners believed there was a niche market available for the manufacturer who could produce a leaner, more agile, more driver-focused German luxury car. Its E3 launched in 2500 and 2800 guises was precisely this machine.

But perhaps it was just a little too athletic and not quite luxurious enough. Powerful (especially the 170-horsepower 2800) and elegant, these were fantastic driver’s cars; among the luxury sedans on offer at the end of the swinging sixties, the BMW recipe was closer to that of the newly launched Jaguar XJ6 than the square-rigged W112 Mercedes. The world’s automotive press loved these new Bavarian machines but there were suggestions that they were perhaps just a touch austere (cloth upholstery not leather, sparing use of timber, wind-up windows).

As the 1500 drove the road towards the 2000 and the -02 two-door models, the E3 – BMW’s first attempt at a true top-end sedan since the 501/502 six-cylinder and V8 flagships of the 1950s – was the precursor of the 7-Series. In the very early 1970s, BMW’s product planners were conceiving their ‘Series’ concept, with the 3-Series as entry level cars, 5-Series in the middle and the 7-Series flagship; later it got more complex!

The original 1972 E12 528 was an extraordinarily charismatic compact sports sedan with more modern styling than the E3 3.0S but almost identical interior room; this was a kind of Bavarian reimagining of the old Jaguar Mark 2 3.8.

Image: https://en.wheelsage.org/

Unsurprisingly, the new 7-Series pursued this styling theme. But it did seem to have taken a long time to come to market. By 1977, the E3 was clearly outdated and could not really be deemed a creditable rival for the brilliant new W116 S-Class which had been around since 1972, let alone the magniloquent 6.9 variant.

In hindsight, it is clear that in conceiving the original E23 ‘Seven’, the BMW planners had not completely taken the measure of their Daimler rivals. The most obvious evidence of this is that there was never a plan to launch a longer-wheelbase edition of the E23, notwithstanding the fact they had felt it necessary to introduce ‘L’ editions of the E3 (doubtless to lift them further above the space-efficient 5-Series).

The first-gen 7-Series was well received but there was no ecstasy evident. Slightly bigger and heavier than its predecessor, this new BMW was still shorter than a Jaguar XJ. Maybe the earlier versions were somewhat underdone with their three-speed automatic transmission and hard-riding Michelin TRX wheel/tyre combinations.

Australian customers were offered no choice. Where Europe got a 728 and a 730, both of which were carbureted and the injected 733i, only the last of these was sold here (with the three-speed ZF automatic transmission).

The UK press produced more positive reviews than their Australian counterparts. Autocar summed up the 733i thus:

New big saloon to replace 2500/3.3 range brings elegance, better equipment and more space. Magnificent engine and transmission; good handling, steering and brakes. A superbly comfortable car except for slightly knobbly ride on poor roads. Low noise level, high performance and relatively good fuel economy.

The English journalist Bob Murray, who was deputy editor of Wheels wrote:

Of course, it has cabin space, equipment, performance and roadholding in abundance, but then the 733i’s price dictates that it must. The price should ensure a smoother and – more importantly – quieter ride, better steering feel at the straight ahead and a better performance/economy balance: excellent it may already be, but this BM, available only as an auto, does nothing in speed or fuel consumption that a $20,000 less expensive Audi 200 Turbo auto can’t.

But Murray noted that the car was about to be greatly improved with a smoother, quieter ride and a four-speed automatic transmission.

My own experience of the E23 dates from 1985 when I road-tested a 735i Executive for a week in Sydney. I had recently sold my much-loved E3 3.0S automatic and was well familiar with the faint praise expressed by Bob Murray for the 733i, so I certainly didn’t expect to conclude that this was the best car I had ever driven.

The Executive had buffalo hide upholstery and an even higher level of standard kit. But I had never guessed a couple of hundred additional cubic centimetres and one more gear ratio could make such a difference. The 733i took 17.3 seconds for the standing 400 metres; the 735i lopped a full second off this time. By comparison the 4.2-litre Jaguar XJ and even the Mercedes-Benz 380SEL felt tardy. This BMW to delight both ardent driver and the unabashed sybarite was a joyous car that shrank around one (as all good big cars do!), coming alive in the hands. I don’t remember faulting it.

Just a year later BMW would launch the second-gen E32 in Germany, initially in 735i guise but with the promise of a 750i and 750iL to follow. However, when the new 735i went on sale locally, its European performance had been compromised by Australian emissions legislation and it could no way match its predecessor. But it did feel somewhat nimbler, despite an increase in weight. This was also the first big BMW to display respect for aerodynamics, its coefficient of drag down from a dreadful 0.42 to a competitive 0.32. Interestingly, the European launch of this model came a week after Jaguar’s presentation of the XJ40 – the British car, too, was somewhat nobbled: indeed, the 3.6-litre XJ40 was notably less accelerative than its German rival.

Of course, the advent of the 750iL (long-wheelbase version for Australia) rewrote the rulebook as I indicated in my introduction. The 733i made 145kW and weighed 1620kg. The V12-powered flagship produced an effortless 200kW and nudged the scales up to 1820kg. It covered the 400m in 15.6 seconds, which got Peter ‘Robbo’ Robinson raving (but had he temporarily forgotten that the 3.0Si he tested in 1973 also stopped the watch at 15.6?). But these were utterly different cars, one a rorty sports luxury sedan with four-on-the-floor, the other the world’s most competent limousine, an almost utterly silent and serene machine. Where the 3.0S was at the sports end of the sports/luxury spectrum, the 750iL shrugged off such distinctions. It was the first ever BMW to eclipse Daimler-Benz at its own game.

Midway through the life of the E32, BMW replaced its lovely 3.5-litre straight six with a pair of V8s, a 3.0-litre (730i) and a 4.0-litre (740i). These were smooth but developed peak torque rather too high in the rpm range to team perfectly with automatic transmission. Within four years both were increased in capacity. Although little remarked upon at the time, it was interesting how BMW had changed its emphasis from four cylinders to six and then, it seemed, to V8s…

In 1994 the third-gen E38 7-Series looked about as little different from its predecessor as the 1981 5-Series had from the original, although in both cases there were all-new and slightly bigger bodies. Clearly, the BMW designers were nervous about departing from a successful formula. This evolutionary model would prove to be the last to follow design themes begun in the early 1970s.

The E38 was slightly bigger in every key dimension and commensurately heavier; here was the epitome of evolution.

But revolution was coming. In 1998 I was in Germany as a guest of BMW for the international launch of the E46 3-Series. Newly appointed design boss Chris Bangle promised that this was to be the last BMW styled on the old evolutionary principle. Eventually, said Bangle, you need to break with tradition and reimagine design. ‘Just wait until you see the first expression of this in the next 7-Series!’

In 2002, the E65 7-Series (and E66 long-wheelbase version) was indeed, as promised, entirely different from anything BMW (or for that matter any other maker) had created before. But while many reviewers disliked the new look, almost all of them complained about the i-Drive system, which used a large chrome knob to cycle through almost countless settings for nearly all major controls outside steering, brakes and engine – removing many switches from the dashboard. It was far from intuitive and BMW progressively modified it over the years to make it less user-unfriendly.

I currently own an early E65 735i (3.6-litre V8, 200kW) and much prefer it to the same-era S-Class I exchanged for it. Big and heavy as it is, the BMW is still every bit the driver’s car. It is also plusher than the Mercedes with beautiful slabs of timber, including one behind and above the rear seat! Interestingly, this radical new model outsold the S-Class in many markets, including ours.

For 2005, the styling was revised mainly to make the controversial rear-end less so. There was more power for the V8s and extra equipment throughout the range, as you’d expect. Blessedly, i-Drive was rendered less labyrinthine. The new entry level was the 740i (4.0-litre V8, 225kW) with the 270kW 4.8-litre V12 750i as flagship.

In 2009, the fifth-gen F01/F02 was as conservatively styled as its predecessor had been radical and many critics believed that BMW had retreated from the Bangle boldness. I, for one, could see no visual appeal in this new one, despite its technical brilliance. In the pre-Bangle era, all BMWs were aesthetically pleasing, but there now seems to be confusion within as to what a BMW should look like: most just look crook!

Self-levelling air suspension was standard, as were run-flat tyres which somewhat compromised the ride quality. There was even a bonded aluminium roof to save 40kg. The instrument panel with head-up display provided a plethora of information at a glance.

Visually, alas, the sixth-gen G11/G12 represent more of the same. The passenger cell is constructed of carbonfibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP), tensile steel and aluminium. All-wheel drive is optional.

There was a time in Australia when new and late-model 7-Series BMWs were frequently sighted in the traffic. But the sight of any upmarket Mercedes, Audi or Lexus is also rare, with many buyers switching their preference to SUVs.

In much the way Holdens and Falcons always felt different from each other, so it has always been with the European luxury brands (and Lexus). The BMW 7-Series has long been the driver’s car among them, a precedent established way back in 1968 when the elegantly understated 2500 and 2800 saloons were introduced.