VH Valiant 50th Anniversary: Styling Really Does Matter

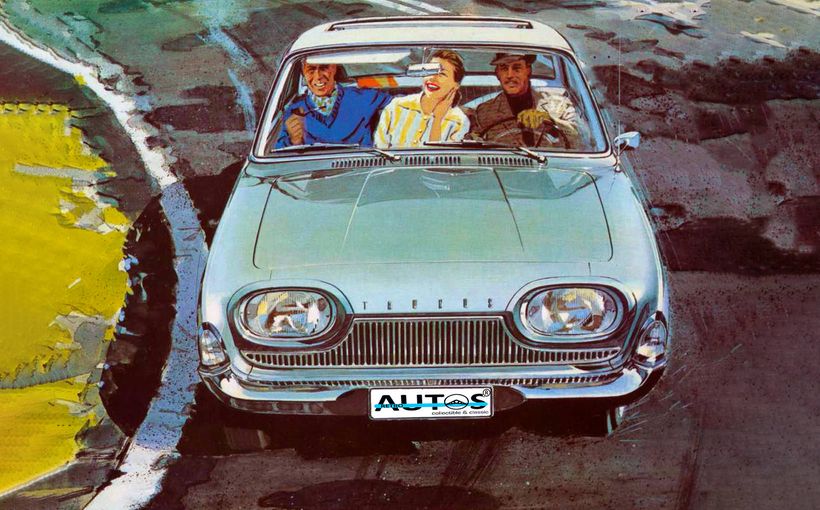

Between June 1971 and March 1972, the Australian car buying public was treated to a rare experience. For the first and last time Chrysler, Holden and Ford—the Big Three—presented their new, “All Australian” versions of the affordable family car, all based on a 111 inch/2819mm wheelbase.

What impressed me then, and still does, was how the three companies created such different styling interpretations, despite similar product planning requirements and dimensions, to address the same market segment.

The VH Valiant was to first to break cover in June 1971. The HQ Holden appeared in July. The XA Falcon was last, debuting in March 1972. In those days Holden commanded 33% of the market, Ford was climbing beyond 22% and Chrysler languished at around 12%.

I was a teenager in 1971 and could not wait to see the VH and HQ at the local dealerships in my town. I’d read and re-read Modern Motor which had run a scoop on the VH in its April 1971 edition. The HQ had been scooped in January 1971 and again in May.

Since their arrival in 1962, Valiants had been a mildly re-styled amalgamation of the American Dodge Dart and Plymouth Valiant. Their sheet metal was mostly sharp edges and straight lines, so an all-new Valiant was eagerly anticipated.

I liked the styling of the VF, but its early 1960s origins and 108 inch/2743mm wheelbase were starting to crimp its appeal. Front seat leg room was great, but the rear legroom and width was noticeably less generous than that found in the XR-XY Falcon and HK-HG Holden.

In my town the Big Three car dealers were located close to each other. When I walked into the Chrysler dealership after the VH’s release it was full of sedans and wagons featuring Chrysler’s corporate “fuselage” styling theme. They looked long, wide and bulky. Surprisingly, the length was only a half inch/13mm more than the VF.

The VH had a distinctive wedge shape in profile, with a rising beltline that was at least two inches/51mm higher than the preceding model. A small window area, thick pillars, wide door frames and a crease line slashing from the front door to the rear fenders in a long arc accentuated the fuselage theme. The crease line defined the way the C pillar met the body, giving it a wide-hipped appearance and a droopy rear end. I subsequently came to understand that all of these design elements would make updating the VH’s appearance very expensive.

The body also looked somewhat too big for its track. I found out later that Chrysler Australia did not have the money to invest in a wider track and basically reused what was under the VE/VF/VG, increasing it by just one inch/25.4mm, despite the body being four inches/102mm wider.

I recall sitting in the back seat of a Ranger XL sedan on the showroom floor and thinking how closed-in—submerged—it felt. I did not relish riding in the back on a long journey. The driving position was low and it was impossible to see the rear of the car from the driver’s seat.

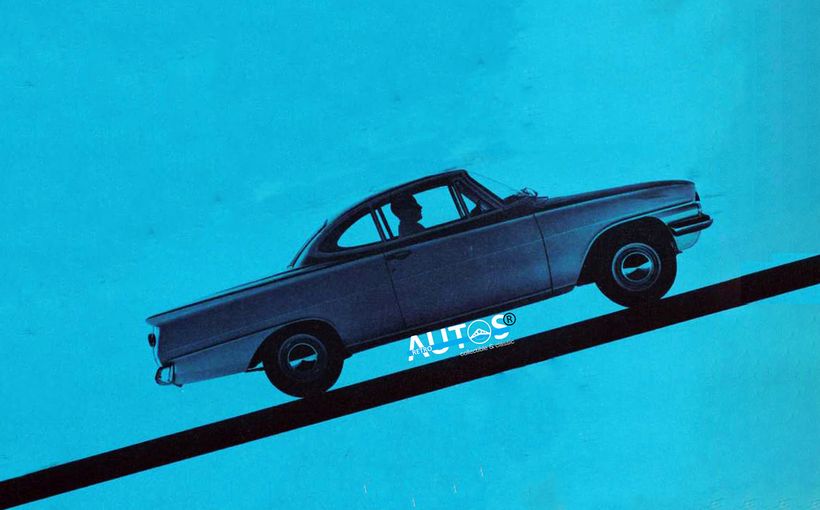

On the Saturday after the HQ was released, I spent a couple of hours at the two Holden dealers. The styling was truly stunning. The panels were as smooth as a river stone, with a low belt line and plenty of glass area. It had the thinnest A pillars I’d ever seen.

Although the wheelbases were the same, the HQ was five inches/127mm shorter than the VH. The design team had nailed the sheet metal to tyre proportions to perfection. From the rear, especially, the fenders tucked under to expose the tyres and give the car a purposeful stance. Sitting in a HQ only reinforced the claustrophobic nature of the VH’s interior.

The VH’s styling program began in the American design studios of Chrysler in Michigan, in late 1967. Chrysler’s Australian styling chief, Brian Smyth, worked with an American team on several carry-over styling proposals based on the existing VE/VF/VG Valiant platform, on a longer wheelbase. Such a car would have looked similar to the 1971 Dart.

But at the top levels in Chrysler Australia, different ideas were forming, motivated by an ambition to build an “All Australian” Valiant.

Since its debut, Chrysler Australia had positioned the Valiant as a cut above its rivals. Their strategy of combining the Dart and Plymouth for Australian tastes was a core skill. The outcome was a more powerful, better equipped and slightly pricier car than its competitors. It found willing buyers.

By 1969 this strategy had helped them reach number three in the market, with almost 14% market share. Trouble was, this is about as good as it got. Inside the company there was a well-founded concern that being a distant number three made it vulnerable to the likes of Toyota, Nissan and Mazda whose sales were climbing. And then there were the rumors of Leyland’s new big car, which would add to the competition.

Chrysler’s managers could also see the up-sizing of the Kingswood and Falcon in the late 1960s. Both gained in length, width and wheelbase, and had fresh “coke bottle” styling themes. They believed the Valiant was being left behind with its narrower body, shorter wheelbase and straight edge styling.

Never financially robust, Chrysler Australia needed a strategy that would deliver increased sales, which, in turn, would ensure increased financial security and provide funds to develop new models into the future. A business-critical decision had to be made. There were basically two strategic choices.

One strategy had Chrysler Australia continuing to sell American-based cars and hope that buyers would stay with the brand. The other involved developing its own “All Australian” Valiant, that would match the Kingswood and Falcon on most dimensions.

The first played to Chrysler Australia’s existing core skills, supported by a known pipeline of future models from the USA. The second brought great risk and uncertainty. Chrysler Australia’s team had never taken a completely new range of cars from design to driveway before. Holden’s managers had been doing it for almost 25 years.

The decision was made. The VH range would be “All Australian”. In late 1967 Chrysler Australia’s managing director, David Brown, went to Chrysler’s American headquarters to start negotiations for the money to fund the program. He must have made a compelling presentation because his strategy was approved, with one proviso. He was given just $22 million to cover the development of the entire range: sedan, wagon and the long wheelbase coupe and sedan.

In the first volume of my Design to Driveway book series, author, publisher and automotive historian, Gavin Farmer, succinctly summarised the risks and rewards of Chrysler’s “All Australian” strategy. “This strategy was very appealing to Chrysler Australia as it struggled to gain market share. In the 1960s and 1970s the Australian family sedan and wagon were the most popular segments of the car market. Success meant a healthy bottom line. But the risk was significant. The downside for Chrysler Australia was that, no matter how appealing the strategy, if the VH did not meet its sales targets the company would not generate sufficient financial resources to continually update the range. They were betting that the VH’s styling would carry them to higher sales, market share and profits.”

Brown must have known that $22 million was never going to be enough to fund the “All Australian” strategy. Holden probably spent more than that on just the HQ sedan. He would later subtract two million dollars and use it to fund the Charger’s development.

The fuselage styling of the VH was confirmed during 1968. After the VH’s release, Wheels magazine pinpointed the main issue Chrysler Australia was to face. In its September 1971 edition it said that the company “will find out if its brand new and massive wedge styling is good enough to grab suburban dads and fleet owners to send its sales graphs climbing from the present 12% to the ambitious 15% it is hoping for.”

Those potential buyers, including the “suburban dads and fleet owners”, delivered a swift and brutal verdict. Just 53,411 VHs were sold between June 1971 to May 1973, which was almost 20,000 units less than the 1967 VE. Farmer captured the essence of it all in his book Valiant—Finest of the Three, commenting that “Chrysler misjudged the styling viewpoint.”

The VH’s sales were so low that in 1973 Chrysler’s market share had slumped to 9.5% and the company was now fourth behind Holden, Ford and Toyota. Had it not been for the Charger coupe’s success, it is highly likely that the business might have folded sometime around 1972-73.

By comparison, Holden sold 300,000+ HQs during the VH’s life span. The XA Falcon sedan and wagon were on the market for only 18 months and attracted more than 111,000 buyers.

Declining sales meant stringent cost containment measures were quickly implemented, restricting future changes. The design team’s plans to re-shape the car for subsequent models were scrapped. Chrysler in the USA could not provide any funding because they too were in a dire financial position.

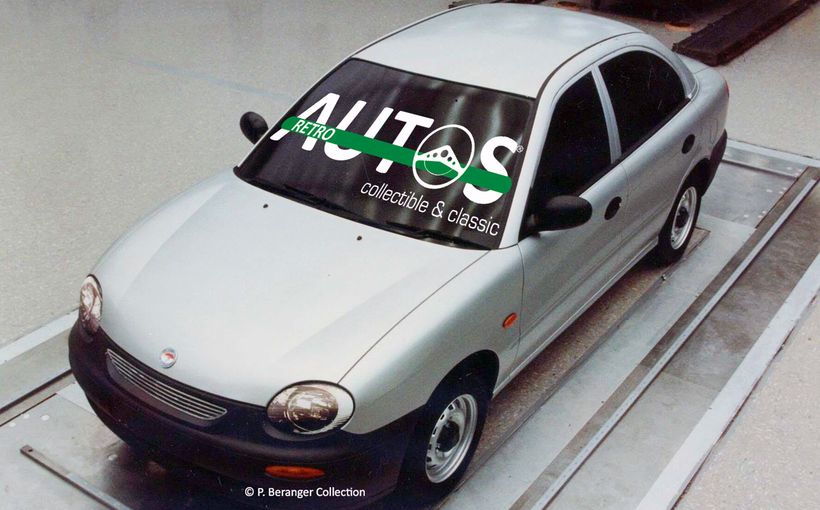

The little changed VJ and VK models were released in May 1973 and October 1975, respectively. The CL followed in 1976 and the CM in 1978. Valiant production ceased at the end of 198. Only 47,000 CL/CMs were sold during those last five years. By then Mitsubishi was firmly in command of the company and its future.

For me, the intriguing question about the VH is why Chrysler Australia took such a big risk on developing an “All Australian” car in the first place, having never taken a new car from design to driveway before? With fifty years of hindsight, I have some thoughts to offer.

The VH story is a powerful reminder that there once was a time in Australia when we considered it a matter of national pride that cars should be designed and built in Australia, of Australian-sourced materials, by Australians, for Australians. “All Australian” cars were an ambitious nation building dream supported by a “Grand Alliance” between the participants: car manufacturers, unions, employees, media, government at all levels and the buying public.

This Grand Alliance was actively encouraged by high levels of tariff protection, state government tax breaks and a proud willingness of Australians to buy a locally made car.

The dreams and ambitions that arose from this Grand Alliance are what propelled Holden to market leadership for so many years. The Grand Alliance motivated Ford to ensure its Falcons were seen as “All Australian”. It is why Leyland embarked on its P76 journey.

I admire the determined ambition of Chrysler Australia to be a major player in that Grand Alliance. Its executives had the enthusiasm and belief that they could succeed with their “All Australian” VH. But, $22 million was never enough to fund an entire range of cars and progress their development into the future. When the VH’s sales slowed, the lack of deep pockets determined the outcome.

Chrysler Australia’s core skill had been converting American automobiles for tough Australian conditions, adding powerful engines, providing higher levels of equipment and selling them a higher price than the competition. Leveraging that skill may have served them better in the long run.

Pursuing the original plan of carry-over VE/VF/VG styling on a longer wheelbase would, perhaps, have been more cost effective, and spanned the period until an Australian version of the new Dodge Aspen and Plymouth Volare twins could be readied. That’s exactly what the Canadians did. No special “All Canadian” Valiant for them, despite having 30% of a much larger market.

Interestingly, the Aspen/Volare idea was evaluated. The September and November 1976 editions of Wheels magazine reported on rumours that the 1977 Valiant would be a localised Aspen/Volare. They revealed that editor Peter Robinson had bluffed his way into a market research clinic in Sydney where a Dodge Aspen was being compared to competitor models.

And then there was the VH’s styling. I have long wondered why Chrysler Australia’s most senior leaders ever approved the VH’s voluminous body. Farmer wrote that Brian Smyth attempted to slim the VH’s appearance but the American designers ignored his advice.

My summary is this: the executives at Chrysler Australia were so focused on achieving their dream of an “All Australian” car, they gave too little attention to the styling and its all-important influence on the buying decisions of mainstream buyers. As I have written before, styling really does matter.

Retroautos is written and published with passion and pride by David Burrell. Thanks to Stellantis Historical Services for many of the images used in this story.