The stunning Phantom concept car was the last hurrah for General Motors (GM) design boss Bill Mitchell. It was to be a fully operable automobile and he commissioned it primarily as a retirement gift for himself.

These days, the long, black Phantom sits, brooding almost, at the Sloan Museum in Flint, Michigan. It is a fibreglass “push mobile”, on a Pontiac Grand Prix chassis. There’s no drive train and the interior is just a mock-up. So, what happened to Mitchell’s dream?

Retroautos has been given access to previously unpublished photos of the Phantom’s creation, thanks to the archivists at the GM Heritage Centre, Michigan.

The story of the Phantom has become the stuff of automotive folklore.

In early 1976 Mitchell could see his GM mandated retirement looming ahead. He’d be 65 years old in July 1977 and gone from GM. He’d been at the company for 42 years. For 20 of those years, he had been the design supremo, only the second person to have held that role. Back then, more people had walked on the moon than led GM’s design efforts. In fact, that holds true even in the 21st century.

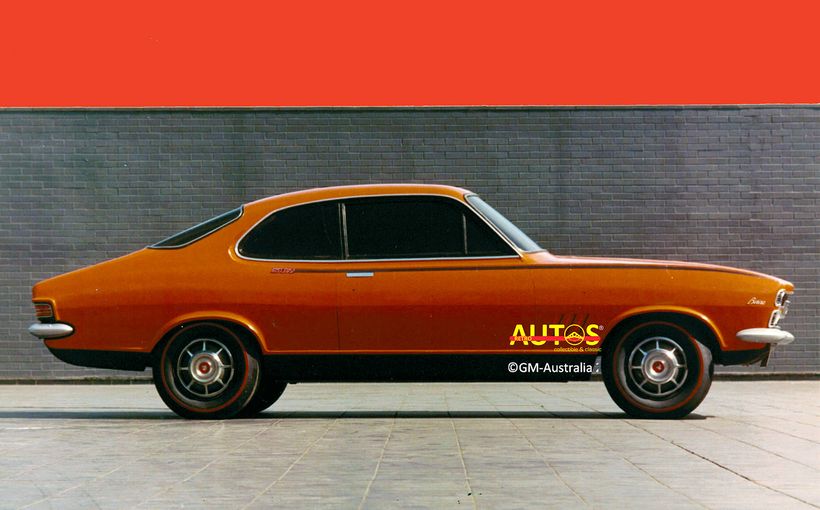

The styling themes which Mitchell had championed ensured GM retained its styling and market leadership through the 1960s and into the 1970s. Iconic cars, large and small, emerged from the company’s design studios across the world. It is estimated that Mitchell influenced the shape of 75+ million vehicles during his tenure.

With Mitchell’s brilliance came a well-documented behavioural downside. He held strident opinions, including views about certain GM executives, which he would share in public. Peter Robinson captured the man in an astute summation in the January 2007 edition of Motor Trend:

“Bill Mitchell was profane, a bigot, often drank to excess, a womanizer and either loved or hated by his designers. But William L. Mitchell….was one of the great car designers, a dictatorial but inspiring leader, a genuinely funny man with a repertoire of tension-defusing one-liners, and, most important, an often visionary design sense.”

With the Phantom, Mitchell wanted a spectacular car that celebrated his achievements. It would be a car in which he could literally drive out of the main gates at the GM Technical Centre in triumph and into a well-earned retirement. And so, he issued orders to re-open his mythical Studio X.

Studio X had been set up by Mitchell in 1958 to allow him and a small group to work on special projects. Its location, in a converted filing room in the basement of the Technical Centre, ensured it was hidden from senior GM executives who might want to stop such projects. From its restricted confines came the 1959 Corvette Stingray Racer (which was the template for the 1963 Stingray), two Mako Shark concepts, Monza SS and GT, Chevrolet Astro I and the mini-Camaro.

A young designer, Bill Davis, was given the task by Mitchell of converting his idea into a reality. What Michell had in mind was a luxury personal car which combined the “classic” shapes of the late 1920s and early 1930s—such as Delahaye, Cord, Duesenberg, Bugatti, Hispano-Suiza—with “Mitchell era” design themes. In other words, modern “retro”.

The classic shapes had long been cherished by Mitchell. He’d been fascinated by them when growing up in New York City. In 1987 he was interviewed by author C. Edson Armi for his book The Art of American Car Design and said:

“I was brought up on big cars. In New York, as a kid, the Isotta-Fraschinis and Hispano-Suizas with long hoods, were always my cars. Not long decks (boots)—I didn’t like the long deck….I’d walk down 57th Street and look at those big cars. Of course I was fortunate enough to have lived in that golden era….but now, they are all boxes.”

Images © Nethercutt Museum and Retroautos.

What Davis delivered was decidedly “retro” and certainly reflected Mitchell’s brief. Commented Holls and Lamm in their book A Century of Automotive Style:

“The Phantom represented that nostalgia Mitchell felt for the classics during those waning days of his vice presidency.”

The first full sized clay was a notchback and originally given the temporary label “Madam X”, in recognition of the Madam X V16 Cadillacs of the early 1930s. After Mitchell saw the full-sized clay, the notchback was replaced with a fastback roof line featuring a split rear window. It sat on wire spoke wheels and was painted silver.

A number of engine configurations were considered, with a V16 the most favoured.

To convert the car into an operational vehicle Mitchell needed one of the divisions to apply money and engineering skills to get it to a point where it could be presented to the GM Board for approval. Pontiac agreed to help.

The clay model was taken to the Pontiac studios where more work was done to refine the exterior shape, bumper bars and interior layout. The car was repainted black and re-named “Phantom”.

A fibreglass body was constructed and fixed to a late 1960s Pontiac Grand Prix chassis. At this point there was no engine, drive train or working suspension. A mock up interior was created, barely visible through the dark Perspex windows. When the work was finished Mitchell posed for publicity photos with the car and a media release was written.

When the media release and photos landed on the desks of car magazine editors around the world what they saw was a striking blend of modern and “retro”. The body lines were curved and voluptuous. The surfaces were smooth and sheer. The bonnet was flamboyantly long and the boot exaggeratedly short. The front end, with its 1930’s “cat-walks” between the razor-sharp fenders and the centre of the bonnet, demanded your attention The rear end elegantly faded away. Minimal “jewellery” and trim adorned the car. Chrome was added only to emphasise a styling line. The scalloped wheel wells were painted red, a reminder of Pontiac’s Strato Star dream car from the 1955 Motorama. So far so good.

But then a few problems started to emerge. In a publicly listed company such as GM, to develop a one off, fully operable metal bodied vehicle, that would then be given free to a retiring corporate vice-president, required significant financial, technical and people resources. Legal and regulatory approval hurdles would need to be overcome. Mitchell would not have had the authority to approve it for himself. More senior executives had that level of power. If he was to realise his vision, Mitchell needed others to advocate on his behalf, especially his boss, Howard Kehrl, who was ten years younger than Mitchell in 1977.

And it was at this point in the story where we return to Holls and Lamm for their almost eye witness description of what happened next.

“Mitchell brought the Phantom to a big GM Board show at the Milford proving grounds. He intended to present it to the corporation’s directors as a surprise. Howard Kehrl, the victim of many a Mitchell insult, spotted the Phantom in the staging area and ordered it removed from the proving grounds forthwith. Mitchell was furious but this was a battle he could not win. His clout had ebbed away, he was too near retirement and no longer had anyone at the top to back him up.”

That was that. Mitchell retired soon after, without the Phantom. Howard Kerhl became the vice-chairman of GM.

At the end of a rarely seen film covering Mitchell’s career and successes, commissioned especially to be shown at his retirement cerebrations, he poses next to the Phantom while the voice over states:

“He leaves a legacy of car designs that express his flair and style, the most recent a two-passenger luxury automobile, the Phantom.”

Then, he gets into his 1959 Stingray Racer and the camera follows him as drives off around a curve and into the distance, leaving the Phantom behind.

As with all concept cars who’s use-by date had expired, the Phantom went into storage awaiting an order for destruction. But a group of GM designers rescued it and a deal was struck to house it at the Sloan Museum in Flint, Michigan.

So, what’s the conclusion about the Phantom?

Stewart Reed, who is the Chair of the Transportation Design department at the Art Centre College of Design in Pasadena, California, from where almost 50% of the worlds’ automotive designers have graduated, put the Phantom into perspective for the book The Art and Colour of General Motors:

“The design represents the last gasp of the qualities that defined the legendary Mitchell era at GM.”

For me it certainly represents an amalgam of many of GM’s best known design themes in one car. It entertains with an outrageous individualism, sinister swagger and dark gothic glamour. Had it been sold as an Eldorado, Toronado or Rivera, I can imagine it stopping traffic and pedestrians as it cruised along the wide avenues and grand boulevards of the great cities of the world. On Woodward Avenue in Detroit, it would have created pandemonium.

The Phantom is Bill Mitchell!

Retroautos is written and published by David Burrell with passion and with pride. A special thanks to John Kyros at the GM Heritage Centre for his research.