Romand Rodbergh: P76 designer. Celebrating his Achievements

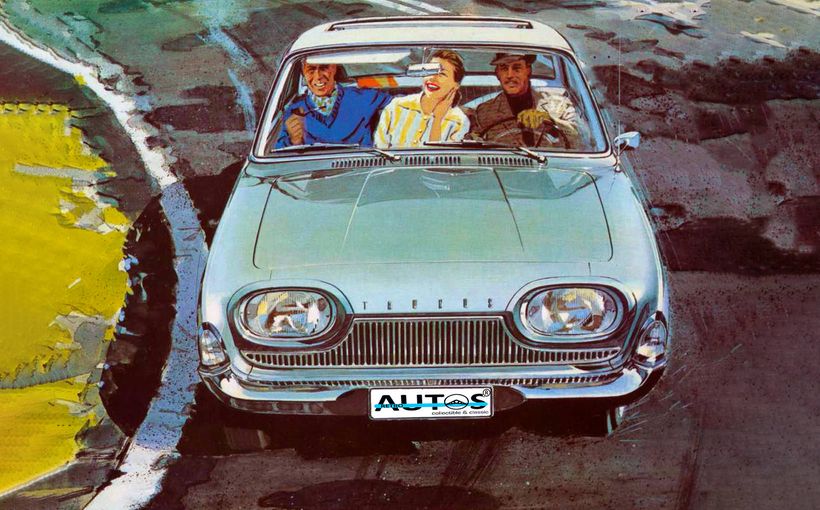

From 1963 to 1970 Romand Rodbergh was the chief of styling for the British Leyland Motor Corporation-Australia (BLMCA). During those seven years, BLMCA was Australia’s fourth largest automotive company. It was Rodbergh’s distinctive wedge-shaped design theme that Italian designer Michelotti re-worked into the P76 sedan and Force 7 coupe.

And yet, Rodbergh’s contribution to BLMCA has often been overlooked.

Styling: Not a Priority

Styling was never the top priority at BLMCA’s UK parent company, the British Motor Corporation (BMC). Here’s what BMC’s technical director Alec Issigonis told the New York Times in 1964:

“I've always felt that stylists, such as you have in America, are ashamed of a car and are preoccupied with making it look like something else, like a submarine or an airship. As an engineer, I revolt against this.”

With that attitude permeating the organisation, BLMCA’s styling studio was part of the engineering department and low in the organisation’s hierarchy. The designers worked in sub-standard conditions. One of those designers, David Hardy, whose career at BLMCA is featured in episode 5 of Shannons Design to Driveway series (see the link at the end of this story), observed that the styling studio:

“Didn't look much different from a mechanical repairs garage. Just concrete a floor, stuff sort of lying around and a couple of car bodies in there.”

Unbelievably, no one in styling was a member of the decision-making committees that oversaw new models, colour selection, trim, badges and upholstery. This lack of professional respect and influence prompted two of Rodbergh’s predecessors to leave.

When Rodbergh first arrived at BLMCA I doubt the senior managers appreciated how fervently he believed in the importance and profession of design. He was unafraid to share his opinions which led him to be labelled as “argumentative”. As Hardy observes:

“Rodbergh was a passionate, fiery sort of character.”

In their co-authored book Secrets of Style, Hardy and fellow BLMCA designers David Bentley, John Holt and Tony Cripps (archivist for the BMC/Leyland Heritage Group) comment that Rodbergh was:

“…the consummate revolutionary. He had a contempt for authority and ‘men in suits’. (He) presented as a non-conformist on first meeting. He had a shaved head at a time when very few men did.”

Resistance

Born in 1915 in Switzerland, the multi-lingual Rodbergh was educated in various European countries. He was drawing boats, cars and airplanes at a young age. By his late teens he was building balsa wood and clay models. He decided to pursue a career in industrial design but WWII intervened. He confided to Bentley that he’d been an operative in the French Resistance during the war.

Arriving in Australia in the mid-1950s, Rodbergh worked as an illustrator for Birds Eye Frozen Foods. While interviewing for an assembly line job at GMH in Melbourne, he mentioned his design skills and was offered a role in the styling studio. In 1960 he was elected as an Associate of the Industrial Design Institute of Australia. He started at BLMCA in early 1963.

New Colours

Joining Rodbergh in the styling studio as his assistant was Bentley. He was an apprentice in the draughting department where his design talent had been noticed. A priority for Rodbergh was improving BLMCA’s colour palette. Said Bentley:

“He had a great eye for selecting the right colours that enhanced a car’s design. One of my first jobs was to help him develop new exterior colours and new vinyl materials for interiors. He let me do the seats and colour trim for the 1964 Wolseley 24/80 Mk II.”

Bentley and Hardy both recall that Rodbergh continually championed the role of styling to the engineers and senior managers, advocating its critical role in the early stages of vehicle/component development. He was largely ignored. Said Hardy:

“They just didn't think of it as anything except what you do at the end to dress it up.”

Push back by management did not deter Rodbergh. During 1965 he envisioned three and five door hatchbacks to eventually replace the Morris 1100. Rodbergh and Bentley developed sketches and scale clay models of the concept. When Rodbergh showed them to his engineering bosses they told him he had wasted his time.

Another shelved project was a considerably thicker steering wheel for the 1100. An engineer told Rodbergh and Bentley that he could not see the need for a thicker wheel, because:

“Everyone steered the car with the spokes, not the rim.”

More successful projects were the Austin 1800 ute and Morris 1500 sedan. But, as Rodbergh lamented to author Gavin Farmer for his comprehensive book Leyland P76: Anything But Average:

“We never had the budget for anything more than a few cosmetic re-arranging’s of the chrome work. It was, for me, not very satisfying work.”

In 1966 Bentley won a scholarship to study at the Birmingham College of Art and Design. While there he assisted with the styling of the Austin Tasman/Kimberley at BMC’s UK design studios. When he returned to Australia in 1968, he could not see a future with BLMCA and resigned. With Rodbergh’s help he expanded his design horizons, eventually establishing a world-renowned boat design consultancy. In 1975, at the request of Wheels editor Peter Robinson, Bentley created sketches of the P76, demonstrating that minimal changes could enhance the car’s appearance.

Defying authority

In mid-1967, development of the P76/Force 7 began. During the next two years the engineers established the car’s “hard points”, including length, wheelbase, width, height, interior dimensions and boot size. Rodbergh was not involved in these decisions. Indeed, no serious attention was given to styling nor if the hard points compromised the shape.

It was only in late 1969 that a Styling Committee was assembled to review design proposals and make a final design decision. Proposals were requested from BMC in the UK, Karmann in Germany and Ital in Italy. Rodbergh was not invited to participate, but created preliminary sketches anyway.

Trouble was, by this late stage, the hard points were non-negotiable. Essentially, the designers were being told to hide the engineers’ hard points with sheet metal.

The review of the design proposals was scheduled for early January 1970. In addition to BLMCA’s top managers, Lord Stokes, chairman of the newly merged British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC) and some of his key executives were to be there. Rodbergh was relegated to arranging the presentations.

Sensing the opportunity, Rodbergh ignored his bosses. Working through the Christmas/New Year holidays he drew more sketches. Hardy admires what he did next:

“Being the rebel he was, Romand decided to add his own design ideas to the presentation without telling anyone. I remember being really impressed that this guy had managed to do that without being asked to and pushing it through.”

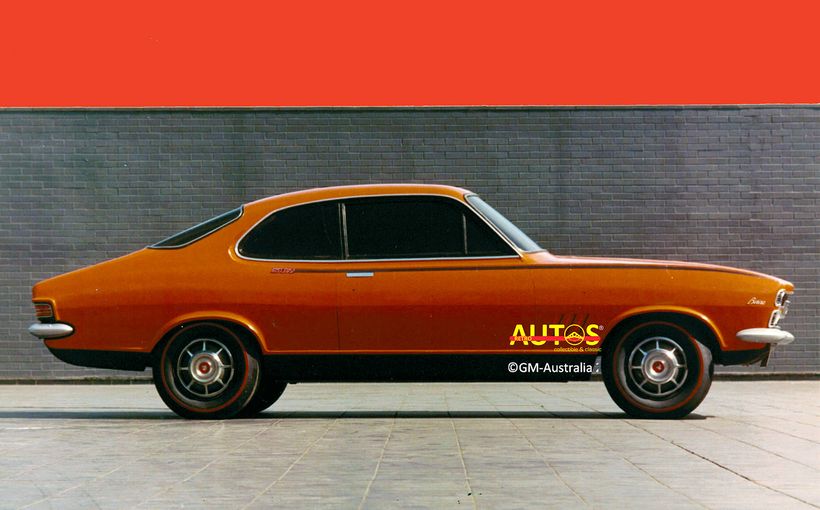

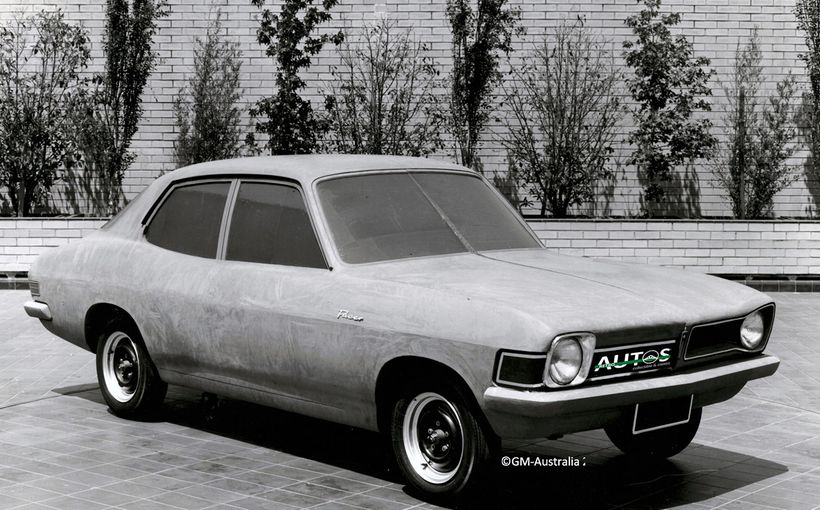

In what must have been a major embarrassment to local executives, Rodbergh’s striking wedge shaped sedan, coupe and wagon were preferred by Stokes and others. He was asked to create three scale clay models—a four and six window sedan and a hardtop coupe. The UK’s sketches were also favoured.

Rodbergh, Hardy and two clay modellers worked long hours during February to build the clay models. They might seem a bit rough to our eyes now, and the photos are blurry, but even in their rudimentary form the wedge shape is integrated and appealing, with a muscular hunkered-down look.

Because BLMCA did not have an adequate design studio, Michelotti in Italy (favoured by BLMC’s new technical director, ex-Triumph executive Harry Webster) was contracted to further develop Rodbergh’s three models (which were to be shipped to Italy) and the UK’s sketches, into quarter scale models.

Michelotti was told that Rodbergh and Graham Hardy, the chief body engineer (and David Hardy’s father), would oversee the work in Turin. You can only guess how that news was received by Michelotti’s team. To add more complications, Michelotti was asked to re-work Rodbergh’s four window sedan and contracted to build full-sized wooden models after the final designs had been approved.

Photo Folly

Rodbergh experienced considerable stress and frustration working at Michelotti’s studio, seven days a week, mostly on his own. Visiting BLMCA managers did not help by demanding changes, including switching Rodbergh’s six window proposal (his favourite) to a four-window design to save costs.

By late March 1970, Rodbergh’s model, Michelotti’s re-work of his original four window car and two-additional proposals created by Michelotti, were ready for a photo session. It was here that BLMCA’s senior executives made a mistake with long term consequences. In his Design to Driveway episode, David Hardy explained that:

“The P76 was approved by management, in Sydney, on the basis of photographs of quarter-scale models sent from Italy, which is ridiculous.”

Rodbergh had already warned BLMCA, in writing, about the dangers of this approach. The slightest design flaw would be magnified four times. Further, it meant that no one at BLMCA would see a full-sized model until months after the final decision. Rodbergh’s professional advice went unheeded.

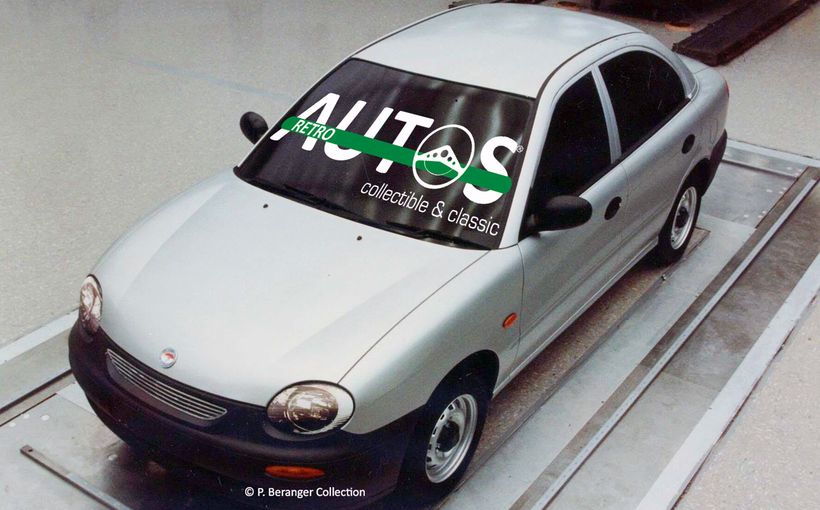

Paul Beranger, the retired design director of Nissan and Toyota in Australia, summed it up succinctly in his excellent book Crayon to CAD. He said that approving a multimillion-dollar design program in this manner was:

“…reckless at best. It reflected a lack of respect for the importance of creative design …and little understanding of the value of aesthetics in the eyes of the consumer.”

When it came time for the official photo session, Rodbergh’s model had to be withdrawn because it had been damaged. He believed it was sabotaged the previous night. He suspected it was doused in solvent which ruined the painted clay. BLMCA’s executives chose Michelotti’s re-work of Rodbergh’s original four window wedge design, which was now devoid of Rodbergh’s hunkered down muscular theme. The only images of Rodbergh’s proposal are those he took himself, a few days prior to the official photo session.

As soon as Rodbergh arrived back in Sydney he resigned. In a letter to BLMCA he complained that:

“I resent being treated like a laborer (sic) although management found my sketches and ideas more interesting than the famous names…for the last 7 years I’ve given honestly the best the most sincere of myself.”

After Rodbergh’s departure, Michelotti re-worked the Force 7’s design. Rodbergh later called this “the attack of the barbarians.”

Beyond BLMCA

Rodbergh moved to Canada where he was the Adjunct Professor of Design at the University of Montreal. Returning to Australia in 1972 he worked for design consultancies. He gained a diploma in yacht design and illustrated the “How It Works” books for publisher Paul Hamlyn. He taught at the Sydney College of Arts and was a founding member of the Australian Society of Marine Artists.

Legacy

What motivated Rodbergh to continue working at BLMCA for seven years was something he kept to himself. Bentley and Hardy believe it was a combination of his never-give-up personality and passionate belief that design mattered. He expected much of himself and the same from others. He may have been outspoken, however, he was always keen to coach and mentor those he believed had talent, and help them further their careers.

From a distance of 50 years, it is easy to forget the impact the P76/Force 7 had on the Australian automotive scene. The P76 V8 won 1973 Wheels Car of the Year. The wedge shape guaranteed it stood apart from its more rounded rivals. Yes, Michelotti modified its appearance, but the overall design theme is Rodbergh’s. It is uncompromisingly different and unmissable. Everyone has an opinion about it. The hardpoints are clearly visible. In all these things it is just like Rodbergh himself.

So, the next time you see a P76/Force7, take a moment to look beyond its appearance and celebrate the fact that the passionate, feisty Romand Rodbergh defied his bosses and created something that is now part of our automotive heritage. He died, aged 91, in 2006.

Watch Shannons Design to Driveway Episode 5: David Hardy

Retroautos® is published with passion and with pride by David Burrell. Special thanks David Bentley and David Hardy. Retroautos® stories and all images are copyrighted. Reproducing them in any format is prohibited. Retroautos® is a registered trademark. Reproducing it in any format is prohibited.