In 1995 an Australian designed and engineered car was chosen by the Indonesian government to be their “People’s Car”.

The car was created by Millard Design Australia. Established by the late Gary Millard in 1990, the company provided design consultancy, CAD services and special project management for the automotive and aviation industry including Holden, GM, Mitsubishi, Ford and McDonnell Douglas. Buick’s 1994 XP2000 concept car was constructed by Millard. Wrote Bill Tuckey in the Australian Financial Review of 4th May, 1998:

“Millard is a jewel in Australia's automotive crown. The only independent design house in the country, it is highly regarded by the world's car makers.”

Paul Beranger was Millard’s chief of design from 1994 to 2002. Paul started his career at Holden’s styling studios in 1968. While there he worked on the HQ-HZ range, LC/LJ and LH/LX Torana and the Gemini. He also developed a two-passenger city car he called the CUB (as in small lion, a play on Holden’s emblem).

In 1988 Paul moved to Nissan Australia as its design boss and then to Millard. In 2002 Toyota head hunted him to establish and direct its Australia design studios. He retired from Toyota in 2012 and set up his own design consultancy. In addition, Paul has contributed to car magazines and authored one of the best books about car design, Crayon to CAD. He owns one of 12 right hand drive Ford powered DeTomaso Mangustas in the world. You can see Paul and his car in episode 13 of Shannons’ DRIVEN. There are links at the end of the story.

Paul recalls how the Indonesian car project started:

“The Indonesian Government’s Strategic Industries Agency, (called BPIS) was planning to increase Indonesian levels of self-sufficiency in key industries. High on the list was a ‘Peoples Car’ for domestic sales, similar to what the Malaysian Government was doing with Proton.”

According to Paul, BPIS had been in discussion with Rover in the UK about such a car. Rover had a long-standing relationship with the Indonesian Government, having supplied Land Rovers to the Indonesian military for decades.

“Rover was willing to design a car, based on the mechanical components of the soon to be obsolete Austin/Rover Metro. But it appears they were unwilling to train Indonesian engineers, who would later be expected to continue the project back to their home country. This was not acceptable to BPIS.”

Meanwhile, the Victorian Government’s Industry Department was eager to promote local automotive capabilities. They frequently hosted in-bound Trade Missions to showcase automotive component and service suppliers. Paul explains what happened next.

“During one such mission by Indonesian Government officials, including those from BPIS, the group visited Millard Design and were immediately impressed with Millard’s design and engineering capabilities and management’s willingness to provide technical training to Indonesian staff. Following extensive negotiations, the BPIS Deputy of Technology, Sudati Suparlin recommended to the Indonesian Government that they cancel future discussions with Rover and instead establish a partnership with Millard, along with a cluster of Australian-based component suppliers, including the Orbital Engine Company, Hella and PBR.”

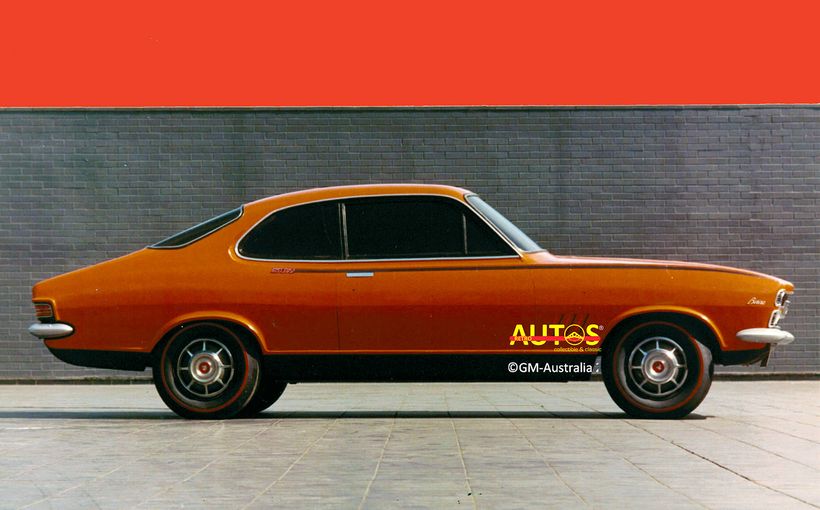

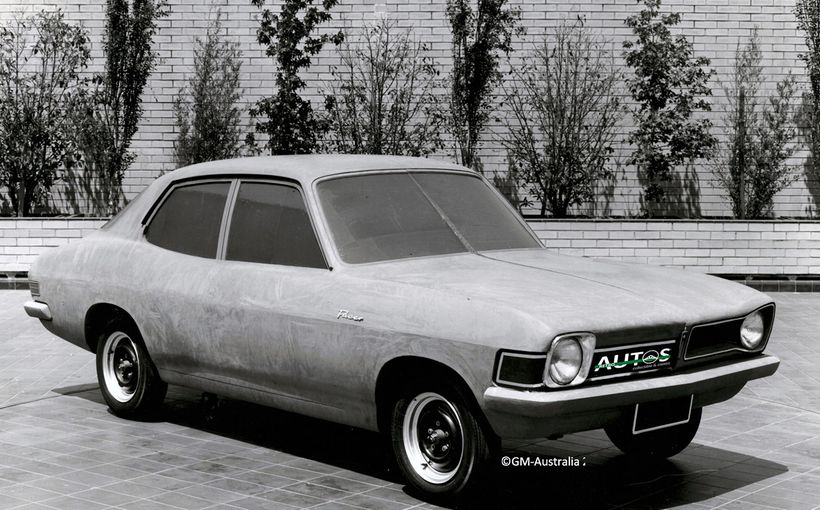

The program scope included initial concept designs followed by engineering, prototyping, testing and production facility preparation. This is equivalent of what any car company would do. The name chosen for the car was Maleo, in recognition of a small bird, native to the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

One of the first tasks was recruiting technical staff and preparing for an influx of up to 150 engineers, many from IPTN, Indonesia’s aircraft industry body, who would be systematically rotated through Millard’s Melbourne facilities. Also recruited to the project was former Holden designer, Chris Emerson and former GM/Holden/Honda designer Bunker Bradley.

With Bunker and Chris joining the team, Paul says the styling pace picked up.

“Our studios in Knoxfield, Victoria, began design and engineering feasibility studies, based on key vehicle design and specification parameters set by BPIS were beginning.

Paul recalls that the short development schedule and tight budget constraints meant some smart thinking was needed to construct the prototypes.

“We purchased twelve Hyundai Excel sedans, which were disassembled, then key structural features such as the floor pan and door pillars, were used for the body design, engine packaging studies, physical prototyping and engine testing. The production car would have a frame that was designed by Millard.”

As the overall design chief, Paul set the styling brief:

“The shape needed to reflect current small-car trends, with short front and rear overhangs and soft rounded forms, somewhat disguising the car’s small size.

The engine selected was a 1.2 litre two stroke developed by the Orbital Engine Company.

On completion and approval of the clay exterior and interior models, the bodies and swing panels (such as doors) were moulded in fibreglass. Five operational prototypes were constructed and another five used in the engineering prototyping workshops to train Indonesian technical staff on the ground-up process of vehicle assembly. A video (there is a link at the end of the story) of the cars was filmed and still survives on YouTube. Paul remembers it fondly:

“The video was created to show the Indonesian government the great progress we had made. It includes some of the Indonesians engineers driving the car. Also seen is Wati Surpalan, a trainee colour and trim designer from Indonesia, and Chris Emmerson, in his cowboy hat.Chris was well respected by the Indonesians for his willingness to share his design knowledge. Sadly, Chris passed away a few years ago. He is biography is featured in Crayon to CAD.”

Then the global economic downturn of 1997 hit the project. Recalls Paul:

“Plans were advanced for the transfer of cars and production jigs to Indonesia, when Indonesia, along with other countries in South East Asia, suffered a significant economic meltdown. President Suharto’s resignation and his replacement by Vice-President Habibie in May 1998 resulted in sweeping reforms, and with them Indonesia’s dream of producing a national car becoming just that.”

For the Australia suppliers, all eager to expand their business, the cancellation was a bitter disappointment. Forecasting export growth, many were in the process of establishing joint-venture relationships with Asian suppliers.

And what of the five completed Maleo cars? Paul says that:

“Completed prototypes, along with engineering drawings and production planning records, were placed into storage, and Indonesian design and engineering staff went home.”

2nd chance

Not long after the cancellation of the Maleo, the Victorian Government hosted another in-bound Industry Trade Mission, this time from Russia. Paul says:

“A key objective of the Russian visit was to evaluate products that could be used to reinvigorate Russian’s ailing manufacturing industry, which had been historically focussed on the manufacture of heavy military hardware, including weapons. During a tour of possible suppliers, including Millard, the delegation was shown a Maleo, from which we had removed all its badges.”

The Russians were impressed and by the time their tour had concluded an agreement had been reached for a left-hand-drive operational prototype to be sent to Moscow and presented to Yuri Luzhkov, the city’s mayor. Paul says that the mayor was someone not easily forgotten:

“Luzhkov was a no-nonsense guy and was in the process of transforming Moscow into the nation’s economic, political and cultural centre, presiding over large construction projects in the city, and committed to continuing operations in the run-down and partially closed ZIL truck and limousine plant, located in an outer-suburb.”

Familiar with tight deadlines, the Millard team wasted no time: Says Paul:

“With the support of the Orbital Engine Company, we fast-tracked conversion of the car. It was air-freighted directly to Moscow, with the cooperation of both Australian and Russian Governments, and stored in a secure building inside the ZIL factory.”

Paul was one of the Australian team who went to Moscow in September 1998 to present the car and was waiting at the ZIL factory for the mayor to make his entrance, recalling that:

“As soon as he got out of his limo, Luzhkov jumped into our untested prototype and accelerated away, disappearing down one of the plant’s potholed roads. Agonising minutes later, to the relief of the assembled visitors, especially Gary Millard, Graham Smith, responsible for the car’s build, and myself, who understood how fragile the working ‘model’ was, it returned intact and all three passengers, plus a beaming Mayor alighted, commenting enthusiastically (in Russian) on the car’s performance.”

As expected, the Millard team was questioned on all aspects of the car’s attributes. Paul remembers that:

“They especially wanted to ensure that the two-stroke engine’s performance could cope with Russia’s cold winters and rough roads.”

After the meeting an event was held at the Australian Embassy, hosted by Australia’s Ambassador to Russia, Ms Ruth Pearce. Letters of Intent were later signed to build the sedan on ZIL’s production line. A launch in 2003 was planned. The Australian media talked up the project. Suddenly, though, it was cancelled. Paul explains why the deal fell through.

“Ongoing financial difficulties between Eastern European banks and the European Bank for Restructure led to the cancellation. The cars were shipped back to Australia and remained in storage in a Melbourne warehouse. They were unceremoniously destroyed.

Legacy

By any measure the Maleo and Russian car projects were a significant achievement for all involved, even if the political and economic events resulted in their cancellation.

What the project did was give additional motivation to a long-held dream of Gary Millard’s to showcase the world class capabilities of Australia’s automotive component suppliers and designers to international automotive manufacturers and suppliers

The outcome of that dream was the one-off concept car, aXcess Australia.

The aXcess program was initiated by Gary, and with the support of 130 independent Australian automotive component manufacturers and designers, the federal government, CSIRO and state governments of Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia, aXcess Australia was released to much acclaim at Parliament House on 9th February, 1998. The car then embarked on an extensive overseas promotional tour throughout North America, Europe and South East Asia.

aXcess Australia was a success. It is estimated that the car generated $A1.25 billion in new export orders for Australian automotive component manufacturers. You can see this contribution to our automotive history at the Victorian Museum. Gary Millard died in 2017.

Paul Beranger’s DeTomaso Mangusta | DRIVEN | Ep 13

Retroautos® is written and published with passion and with pride by David Burrell. A special thanks to Paul Beranger. Retroautos® stories and images are copyrighted. Reproducing them in any format is prohibited. Retroautos® is a registered trademark. Reproducing it in any format is prohibited.