In July 1966 Joan Klatil had graduated with a Fine Arts/Industrial Design degree from the renowned Cleveland Institute of Arts. She was offered a designer job at GM. Just six months later she was promoted into the production styling studio of GM’s most prestigious brand: Cadillac.

Not everyone got to work in the Cadillac studio. Not everyone was allowed to shape GM’s Standard of the World. It was a swift rise in a very short time by any measure. Even today, such a career trajectory would identify the individual as a high potential and someone any smart corporation would want to retain.

Back in 1967, Joan’s appointment was even bigger news. It was pioneering. Here’s how the Cleveland Institute’s newsletter described Joan’s new job, in a tone that was so common of the times.

“The photogenic Joan, first woman designer assigned to a production passenger car exterior design studio in the United States, has been written up in feature articles in several major dailies, including The New York Times, The Detroit Free Press, and The Cleveland Press. Accustomed to ‘firsts’, she joined Cadillac Styling Studio of General Motors Corporation in July last year, after being the first woman to receive the institute’s Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree with a major in Industrial Design. While many women have worked on interior design and styling of Detroit's major product since World War II, not until now has a female designer worked on automotive exteriors.”

Joan recalls the media attention given to her.

“It was the PR people at GM who wanted to publicise the job. Newspapers interviewed me. All I wanted to do was design cars.”

Only two of the newspaper stories refrained from commenting on Joan’s appearance. Descriptions used by the others included “attractive”, “tall slim blonde”, “dark eyed” and “a pioneer in high heels.” It makes for cringeworthy reading now, but back in 1967 such descriptions were commonplace.

The publicity had flow on effects, Joan told me.

“A few of the men in the various studios were jealous of the publicity.”

Joan was not GM’s first woman designer. Helene Rother was hired in 1943 by Harley Earl, GM’s then design supremo. Her work was restricted to interiors. She left GM in 1947.

Earl then recruited ten women in 1955. Widely publicised by GM’s PR department in publicity films, magazines and newspaper stories as the “Damsels of Design” their work was also confined to interiors. There are many recent magazine and online stories that delve into the careers and impact of these talented women. All tend to end with the same observation: when Bill Mitchell succeeded Earl in 1958, the advancement of women in GM’s design studios was curtailed.

GM was not alone in having these attitudes. Sexism was ingrained in most industries in the USA and across the world. Joan now laughs about a Michigan law that prevented women from working beyond midnight, but in 1967 companies could be fined heavily for a breach.

“That Michigan law meant that I could not work all-nighters, as sometimes happened in the design studios.”

So, what drew Joan to automotive design in the first place?

“I played with cars when I was young. My dad bought me model cars and my mother bought me dolls. The dolls remained untouched. I still have a remote-controlled car my dad got me one time. I also constructed plastic car kits. I guess you could say I was the little girl who liked cars.

My parents wanted me to have a university degree. I was good at drawing during high school so I was able to get into the Cleveland Institute. That’s where I really blossomed. “

It was GM designers Chuck Jordan and David North who first identified Joan’s talent. They would visit design schools and offer three-month summer internships to the most promising students. Joan was in the fourth year of her five-year degree at the time.

Joan recalls that summer program.

“GM took me into their summer intern program in 1965. I designed a small electric powered commuter car with a slide out motor at the rear. It must have impressed them because when I graduated in June 1966, I was hired.”

During her internship, Joan became aware of Bill Mitchell, GM’s boss of design, and his profanity. It did not bother her. What she was not aware of at the time, however, was that Mitchell did not want women working in “his” styling studios.

Ignoring Mitchell’s opinion, Jordan offered Joan a job and she accepted. “I wanted to work with the best, which was GM”, she told me.

Like all new recruits to GM’s styling department, Joan was assigned to the design development studio for the first six months. It was managed by North, who also had responsibility for running GM’s designer recruitment and training programme. By January 1967 North believed Joan was ready for an assignment in a production studio. He recalls discussing it with Jordan.

“I said to him that Joan was ready for an exterior studio and suggested Cadillac. Stan Parker, who ran the Cadillac studio, was in agreement. Chuck approved the move. We really didn’t tell Mitchell.”

Joan’s work in the Cadillac studio focused on the 1970 and 1971 cars. She remembers those early days.

“The job was not without its challenges. There were male restrooms in each studio, but no female restrooms. So, I had to walk outside of the studio to find one. It was like the scene out of the movie Hidden Figures. GM also had a policy which prohibited women from wearing long pants.”

What?

“Yes, can you believe it? GM’s dress code compelled me to wear a skirt. Because the designers’ drafting tables were positioned up high, the clay modellers worked slightly below us. To prevent them from being ‘distracted’, they fixed a plastic skirt around my table.”

I asked Joan if there was any reaction from the male designers.

“I think it was harder for them to get used to me, than for me to get used to them. Some did not like a woman being there, ‘invading’ their territory, but most were ok. Often when it was necessary to get down on all fours to work with certain materials, one of the men might rush to my ‘aid’. While this was very kind, I was taught to do these things in school and never found any aspect of the job beyond my physical capabilities."

One thing Joan did do was sign her designs and sketches as ‘Klatil’, to remove any bias when her work was being presented.

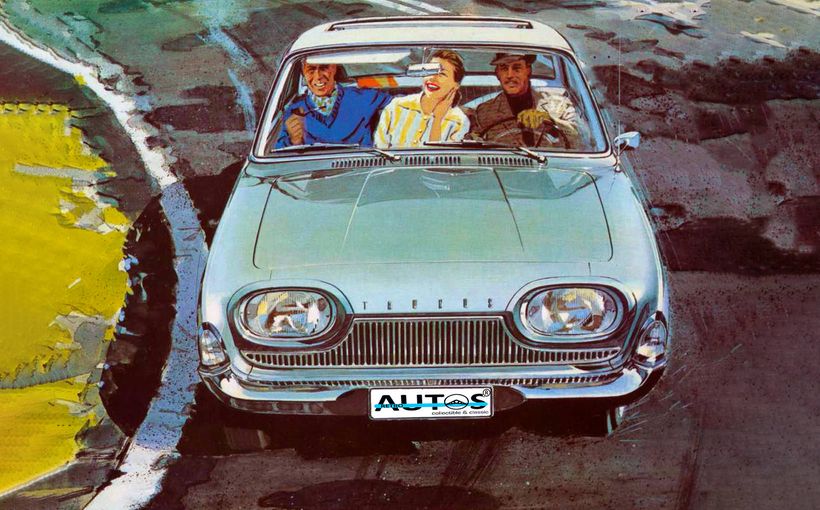

When Joan began in the Cadillac studio GM was riding high. The 1967 Eldorado had been released to rave reviews. The Camaro and Firebird were finally challenging the Mustang. Pontiac was still a performance brand and the Chevrolet Impala was America’s top selling car. Yes, GM was the place to be for talented designers and Cadillac was the most coveted studio in which to work. Mitchell had run Cadillac design and so had Jordan. Only the top talents were allowed to work on GM’s luxury cars and Joan was involved across the Cadillac range, from the Eldorado to proposals for 1971 and beyond.

But, if you thought Mitchell had come to terms with a woman designing “his” cars, then you would be mistaken. One day in early 1968 Mitchell was in the Cadillac studio and launched into a profanity laded criticism of a proposed design. Joan was within hearing distance.

Joan explains what happened next.

“He forgot I was there. As soon as he realised that I was there and had heard what he’d said, he was intensely embarrassed. He went bright red in the face and angrily stormed out of the studio. It did not bother me what he was saying. I was an adult and had heard it all before. I found out later that he ordered Stan Parker to tell me that I was being moved immediately to the Oldsmobile interior design studio, where there were other female designers.”

Stan Parker, who thought Mitchell’s decision was unfair, could not bring himself to tell her of it. Joan explains what happen the next day.

“Irv Rybicki informed me. Chuck Jordan was then at Opel in Germany and could not intervene in the decision. I reluctantly went to Oldsmobile.”

When speaking with Joan it is clear that Mitchell’s decision still rankles with her. And so it should. It is an example of the guy’s character that, for me, will always detract from his reputation as a designer. She was moved not because of her work, but because of her gender. Behaviour like that these days would most likely see the offending manager dismissed and an abject apology issued.

In the Oldsmobile studio Joan designed seats and interior trim, which was not what she’d been trained to do.

“With my industrial design training I knew how to design for hard metals, for exteriors. Soft interiors were not my thing. I loved to design for reflections.”

Behind the scenes a number of the senior design managers, including Rybiki, Jordan and North, were looking for ways to return Joan to exterior design. The PR department, realising they could no longer involve her in publicity activities, also started to apply pressure for a return to exterior design.

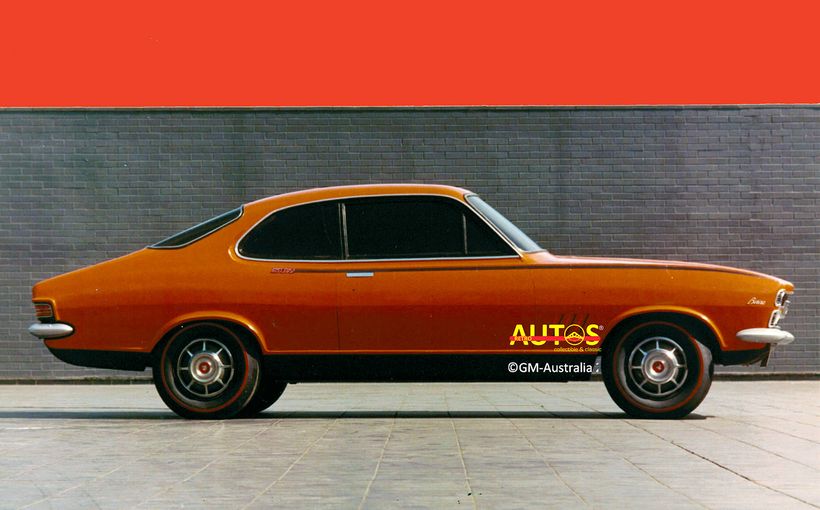

In late 1968 Joan was quietly transferred to Jerry Hirshberg’s Advanced Buick studio, which was working on the boat-tail 1971 Riviera. Hirschberg had graduated three years ahead of Joan from the Cleveland Institute.

To protect her from Mitchell when he’d visit the studio, Hirschberg’s team often placed large wheeled display boards in front of Joan’s work area to ensure she was not in his eyeline.

Such a situation could not last forever, and Joan, more than anyone, knew her automotive design career was at the whim of Mitchell’s day-to-day mood swings. Not wanting to work in that sort of environment she had already begun looking around for a more female-friendly workplace. In 1969 GE offered her a role. It was GM’s loss and GE’s gain. Said Joan:

“GE wanted me on their design team but I really did not want to go. But I thought that if Mitchell gets upset again, then I’d be back to interiors. That was the end of my career with GM.”

After Mitchell retired at the end of 1977, Irv Rybicki, his successor, began to hire women in design roles.

Joan never returned to the automotive industry after leaving GM. She was with GE for eight years, designing consumer appliances. After GE she worked at Textron as a product manager and then was the design director at picture frame maker Burnes of Boston. In 1987 Joan opened her own design and product development consultancy focused on the consumer gift, jewellery and stationary arts. There is a link at the end of this story to her website.

In 2003 Joan was commissioned to create the decorative Easter eggs for the First Lady of the USA, Laura Bush. Joan also has authored and illustrated a book series for children called the Magic Sceptre.

A few years ago, Joan was invited to join the League of Retired Automobile Designers. Each year this group meets and each member designs an updated car of a selected marque. They start with the original design then envision it for the 21st century.

Joan is also in demand as a judge at classic car events. In late 2021 she was at the Audrain Auto Museum Concours de Elegance, on Rhode Island, with fellow judge, Ed Welburn, GM’s retired design vice president. More recently she has judged at the Boca Raton Concours in Florida and the Greenbrier Concours in West Virginia.

The senior leaders at GM design studios are well aware of Joan’s unique role in the company’s history. While at the 2021 Eyes on Design car event in Michigan, Joan was sought out by current GM design boss Mike Simcoe and given a personal tour of the design studios.

“It was great to be back at the Tech Centre and to see so many women designers.”

Looking back on her years at GM, Joan recalls the passion of the teams she worked with and her own passion for automotive design.

“I loved it. I can’t tell you how much I wanted it.”

Retroautos is written and published with passion and with pride. All content is the copyright of Shannons, Retroautos, GM Media and Joan Klatil-Creamer. Reproducing this content in any format is prohibited. Thanks to David North who introduced me to Joan. Thanks also to John Kyros at the GM Heritage Centre for researching Joan’s drawings.