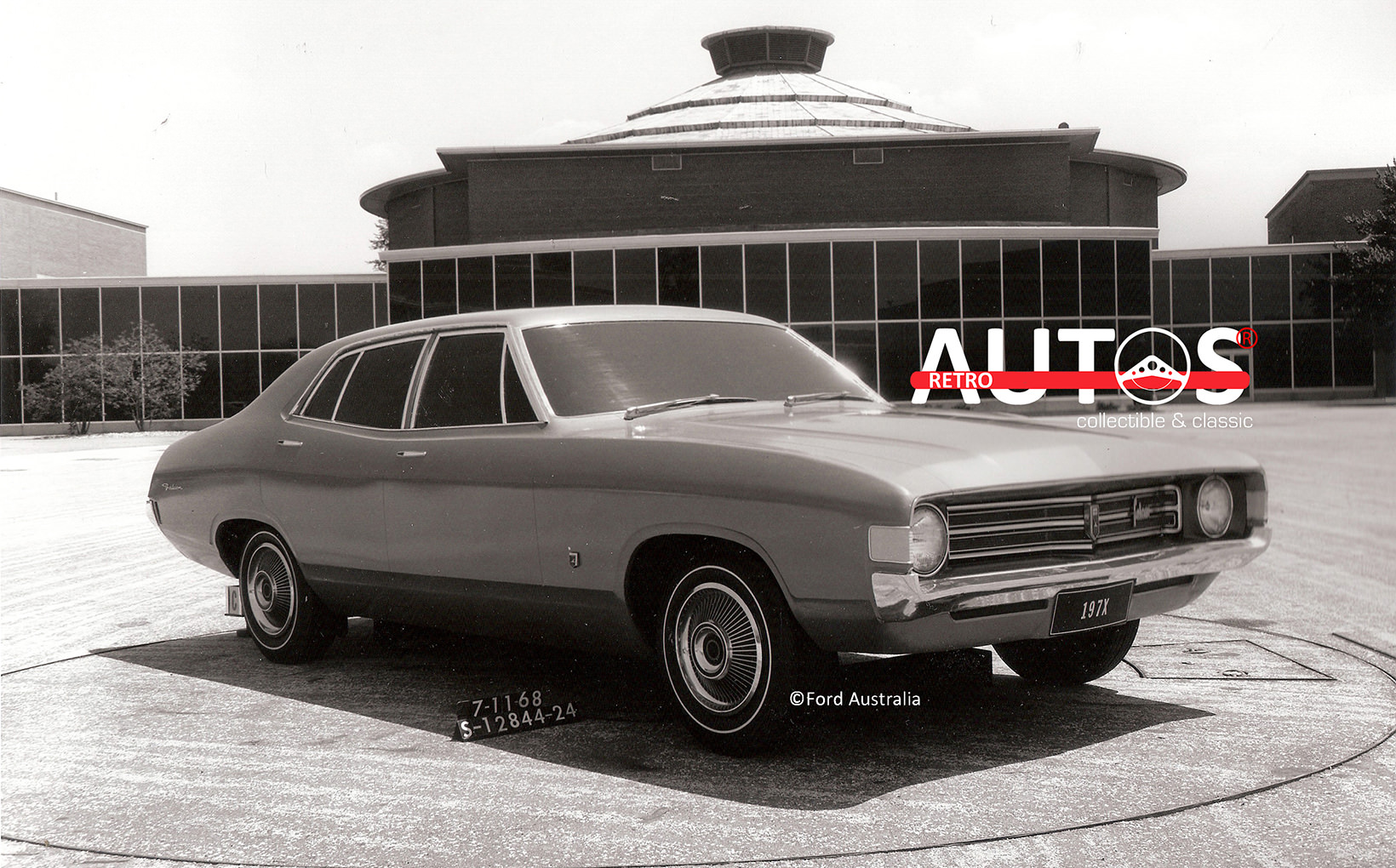

50th Anniversary: XA Falcon and ZF Fairlane

The first time I saw the XA Falcon up close was in March 1972 when a friend and I walked into Kloster Ford in Newcastle. The VH Valiant and HQ Holden had been released nine months previously, and we were keen to see Ford’s all-new car.

In the middle of the showroom was a bronze painted Fairmont with a parchment interior. Wow! It looked long, wide, low and ruggedly aggressive. Although I liked the Valiant’s bulky body, and thought the HQ was a standout design, the XA’s stretched bonnet, short boot and coke bottle styling gave it an undisputed presence. It looked like a car that was meant to be driven.

Fast forward 47 years and I am chatting with Jack Telnack. Jack retired as Ford’s global design boss in 1998 after a 40-year career that saw him champion industry leading designs. From late 1966 to mid-1969 he was the first design director of Ford Australia and led the team which crafted the XA and ZF. I tell him about walking into Kloster’s that day in 1972 and my initial reaction. He smiles and says with pride in his voice:

“I'm a bit biased but I think the XA still looks great and Brian Rossi deserves lots of credit for it.”

The arrival of the XA was the second time in a decade (the previous being in 1962), that the “Big Three” car makers offered completely restyled, similar sized, multi-engined, affordable family cars at the same time. All were built and designed in Australia. Each used the basic sedan to create a long wheelbase luxury limo, station wagon, commercial and coupe versions. It was a moment in time.

Ford released the sedan, wagon and Fairlane ahead of the XA coupe and commercials. The two-door hardtop did not appear until August 1972 and the commercials eight weeks later. I’ll be showcasing the 50th anniversary of the coupe, soon, in Retroautos. The best article I’ve read about the XA commercials is written by Mark Oastler in the Super Models section of Shannons Club. I’ve included a link at the end of this story.

In its April 1972 edition Wheels magazine emphasised the importance of the XA.

“Ford’s new XA Falcon is undoubtedly the most important model the company has ever released. Its bold new lines could carry Ford to sales leadership in Australia in the present decade. The XA is all Australian. It was conceived, engineered and styled locally.”

XA and ZF: Design to driveway.

How the XA and ZF went from design to driveway is another of those stories which highlights the “can-do-make-do” spirit that was so much a part of our automotive industry.

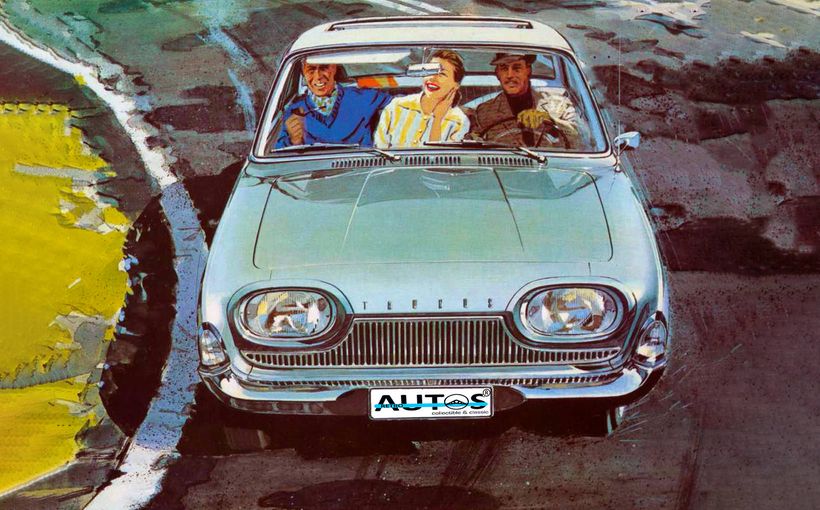

Its development really began during late 1966 and early 1967, when Bill Bourke, Ford Australia’s managing director, faced two fundamental issues concerning the future of the Falcon.

Firstly, he knew that if Ford Australia wanted to be number one in Australia, the Falcon had to be considered a stylish and rugged All-Australian car. It could not be a locally built clone of something from the USA. To this end, Ford Australia had been progressively distancing the Falcon’s styling and engineering from its US counterpart. Although the XP, XW and XY models were important steps in this transition, the XA needed to visibly make the break once and for all. (You can read more about the XW’s journey from design to driveway in the October 2020 edition of Retroautos. There’s a link at the end of this story.)

The second issue was that the US Falcon had a fading importance in Ford’s line-up. Its sales were diminishing. The smaller, stylish and cheaper Maverick was in the pipeline for 1969. The even smaller and cheaper Pinto was planned for 1971. Further, the Falcon was unable to meet new safety laws without expensive engineering modifications. In short, the Falcon’s days were numbered.

In early 1968 Ford’s top executives decided to discontinue the US Falcon during 1970. That meant that Ford Australia would have to find an alternative within Ford’s range of cars in the UK, Germany or the USA, or develop its own car.

Bourke formed a team which included Malcolm Inglis, the Falcon planning manager, and Jack Telnack, to evaluate the alternatives. Whatever was chosen it could not be any smaller than the XY and ZC models it was to replace.

The team was blessed with some good fortune. It just so happened that David M. Ford (no relation), a young product planner at the time, was nearing the end of a 12-month overseas assignment. He’d been sent to work in Ford’s Product Planning and related offices in the USA and Europe to learn the latest techniques. With the insights he had gained about the current and proposed models, he was ideally placed to provide information about the possible alternatives, especially the UK Zephyr/Granada and American Maverick. David recalls the situation.

“The Zephyr/Granada was built to take V4 and V6 engines and the car was smaller than what we wanted in a Falcon. There was no way we could financially justify throwing away our significant investment in our in-line six cylinder and V8 engines, and all of the marketing goodwill we’d built up with the GT Falcon. Plus, we had the Fairlane to think of, too. Hence, we would have had to re-engineer the car to take our engines, similar to what Holden had to do with the VB Commodore in the 1970s. We would have also had to stretch it to make the Fairlane. There were no commercial and station wagon versions either, so we would have had to develop those ourselves. This was all just too costly and time consuming and the idea was shelved.”

So, what about the Maverick? David explains why it was not suited as a potential Falcon.

“When it was being evaluated in early 1968 it was only planned as a two-door coupe with a six-cylinder engine. It was too narrow and too short, with only a 104 inch/2642mm wheelbase. There were no commercials, no wagon, no long wheelbase version and no four-door sedan. Basically, the issues that applied to the Zephyr/Granada applied to the Maverick, and it was ruled out, too.”

When all the numbers were crunched the most cost-effective approach was to use a widened version of the existing Falcon platform with a locally designed new body. David sums the decision.

“We could afford a completely restyled body on the existing platform, driveline and suspensions. Huge savings were achieved in the manufacturing and assembly factories because we could build the XA on the same production line as the XW/XY and continue to use the same I6/V8 engines, transmissions and rear axles. Avoiding major changes in these areas contributed to massive retooling investment and engineering savings.”

With the enthusiastic support of Ford’s President Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen, the development of the all-Australian XA and ZF range was given the go ahead in mid-1968.

Jack picks up the story:

“Bunkie had to sign off on the car as it progressed through its design phases, so he decided that rather than come out to Australia every six to eight weeks to review progress, he asked us to go to Dearborn and work on it there.”

This offer was a unique opportunity for the young team, which also comprised Brian Rossi, Allan Jackson and John Doughty, all barely 30 years of age, to showcase what could be done in Australia.

Meantime, David Ford was finishing his overseas secondment by spending a week’s vacation in Paris with his wife before returning to Australia. Malcom Inglis tracked him down to his hotel. David recalls the conversation.

“Malcolm said that there had been a rapid number of decisions about the XA and, because I had a current American work visa, and I was familiar with the Falcon’s product planning background I was to get myself on a jet to Dearborn immediately rather than come home to Australia. He said I was to start to compile all of the “hard points” for the product planning brief that would be given to the styling team.”

By hard points David means all of the crucial exterior and interior dimensions of the car such as cowl height, width, length, track, height, wheelbase, front and rear overhang, leg room and boot space. It is an exacting task and sets the styling parameters for the design team.

David continues: “I was only in my late 20’s at the time for such an important job, but I was right there, I had the work visa and we needed to move quickly.”

Because of David’s planning work in Dearborn, Jack told me that he and his team had a head start on the styling.

“Before we left for Dearborn, we knew the approximate proportions of the car. Brian and Allan sketched some ideas in advance. We wanted a fast (sloping) rear window and flush C pillars that flowed into the rear fenders. It was a simple design because we only had the time and resources to do one basic design and we zeroed in on it very quickly.”

While Jack and his team were roughing out the XA in Australia, the Americans wanted to assess the feasibility of using a short wheelbase version of the upcoming 1972 Torino for the Falcon. That meant a 6 inch/150mm reduction in the Torino’s 117 inch/2972mm wheelbase and retention of the American front and rear overhangs. The Fairlane would be a localised version of the Torino. From a business and cost containment perspective it was the right question to ask, but as David Ford says.

“It would have meant a bigger exterior and a pudgy, ungainly looking car, with the wrong proportions.”

The idea was quickly dropped.

The important sheet metal to tyre ratio

Ford’s design team and planners wanted the XA to have a visibly wide and road hugging stance. Jack refers to this as the “sheet metal to tyre ratio.” They did not want the XA to look under-tyred, as happened with the HD Holden and VH Valiant. It was achieved by widening the XY’s track by 1.5 inches/38mm, front and rear, and tucking-under the lower half of the body and fenders to reveal the tyres.

When Jack, Brian and Steve arrived in the USA they found out that a small team of Americans, led by a former GM designer, David Wheeler, who was a friend of Knudsen (who was the former general manager of Pontiac and Chevrolet) would also develop their version of the Falcon in order to provide an alternative design.

Jack and his team were allocated a small design studio. He recalls that:

“Gene Bordinat, the global vice president of Ford Design, was incredibly supportive and gave us plenty of help with clay modellers and equipment. Bunkie and Bill would decide which design they liked best and that’s what would go into production.”

The American proposal featured a distinctive side crease similar to what appeared on the 1972 Torino. The Australian proposal with its smooth flanks and simpler design, was more reflected the current Mercury Montego. An absence of accentuated creases and complex shapes in the sheet metal made it less costly to manufacture, an important consideration in a low volume market such as Australia.

Both proposals were reviewed on July 2nd, 1968. David Wheeler made his case for his proposal and Jack followed.

“We said we are living in Australia, we have an idea what Holden and Chrysler are doing, so we are confident that we have the design that will appeal to Australians and fit in to what is on the road there.”

According to Jack, after some discussion with Bourke, Bunkie turned to the Australian team as said:

“Ok, you guys know what’s going on there, so I approve it.”

Jack and the team were elated.

“We were just ecstatic that he approved our design. We were a small group and here was the HQ saying yes to us. It was a big vote of confidence.”

The late Brian Rossi remembered the day.

“Both cars looked good, but I think the difference was our design was simpler and had more road presence, and we also had Jack’s excellent presentations skills and ability to really sell a design. That made all the difference.”

During the next couple of months the XA’s shape was refined. Work also began on the wagon and Fairlane.

More for your money

The overall strategy with the XA was to make it look bigger and offer noticeably visible more value than the HQ Holden and VH Valiant, at a similar price point.

Although the car appeared longer than the HQ, it was actually one inch/25mm shorter. The impression of more sheet metal for your money allowed Ford dealers to refer to the “smaller” HQ, a line I overheard a salesman say to a potential customer when I first saw the XA at our local dealership.

The station wagon was released at the same time as the sedan. It used the Fairlane’s 116 inch/2946mm wheelbase to good effect, enabling Ford to boast about its load carrying capacity. I reckon the XA wagon was the best looking of the three.

Following the strategy set by the XW/XY, Ford offered a larger and more powerful standard engine than Holden on a model-by-model basis.

The interior of the XA was deliberately plusher, and the seats plumper, than its rivals. John Doughty, managed the interior styling. Says Jack:

“John was responsible for all of our interiors starting with the XT Falcon. He directed the designs of all Ford instrument panels, trim and colour development.”

The wide wrap around dashboard was driver focused. The steering wheel was given a more horizontal angle. The outcome was a driving position that conveyed the distinct sense of being in command. All of this fed into Ford’s “Great Australian Road Car” marketing theme.

ZF Fairlane: Stylish sales leader

The late Brian Rossi did most of the work on the Fairlane. It followed the styling theme of the Falcon and the design was locked away by mid-September 1968. Even so, tail light variations were still being considered just three months before its 1972 release.

The ZF’s styling has been criticised for being too Falcon-like. Indeed, the front and rear ends were originally planned to be more distinctive, more like what appeared on the 1976 ZH model. Cost pressures meant the sharing of fenders and other components was necessary across the XA and ZF range.

Sharing styling themes with Falcon did not bother the ZF’s buyers. During its 17 months on the market it achieved 17,300 sales, which was 35% higher than any previous Fairlane. It outsold the HQ Statesman by 3:1. Clearly, the ZF was a popular car.

The XA and ZF legacy

From my perspective, the legacy of the XA and ZF is that it represents a crucial point in Ford’s climb to market leadership in Australia. For the first time since 1960 Ford Australia’s executives could claim with conviction their Falcons and Fairlanes were designed in, and for, Australia.

Although the XA and ZF did not push Holden from its top-ranking position, these models continued the work of embedding the Falcon and Fairlane brands as being All Australian. Ford was rewarded with an increase in market share to 23% and Falcon and Fairlane annual sales continued to climb above 120,000 units, ensuring a healthy revenue stream.

By 1982 Ford was number one.

The design to driveway story of the XA coupe will be published soon in Retroautos. For more on the XA Commercials, Mark Oastler’s Super Models article is a must read. Read the Retroautos XW Falcon story.

Retroautos is published with passion and with pride. Special thanks to Jack Telnack, David M. Ford and the late Brian Rossi for their insights and comments. The Retroautos logo and the stories and images are copyrighted. Reproducing them in any format is prohibited.