Words Michael Harvey | Photography Ian Dawson and Autocar & Motor

Healthy, big-lunged and dominated by the intake rush, this is like no engine you've ever heard. Forget Lamborghinis and ignore Jaguar racing engines, bring Ferraris into the equation only if you're prepared to go back 20 years. Outside, it's a low-pitched turbine-style buzz. Inside, it's raw and rapid, racing along to the beat from the intake trumpets. It's not the painful blast of a modern grand prix engine, nor the fire-crackle of a '50s Silver Arrow; it's just gloriously, sonorously, potent.

We're belted-in at Silverstone. In the central seat, at the sharp end, Jonathan Palmer is not going crazy. He doesn't have to. There's room enough for him to show, even on its first public outing, that the McLaren F1 has what it takes to make you forget everything you thought you knew about fast cars.

How quick is it? At the end of Hangar Straight we touch 175 miles an hour.

"Into a balls-out corner like Stowe," says Palmer of Silverstone's fastest bend, "the McLaren grand prix car pulls something like 187 mph with Mika Hakkinen driving it. The F1 road car pulls 175!"

There isn't an absolute top speed figure just yet. That will have to wait until the F1 goes to Goodyear's 400 km/h Fort Stockton bowl in September. For now, 175 mph (280 km/h) is considered "low speed work" by the McLaren engineers.

As yet not fully developed, it is blisteringly quick, partly because it doesn't have the speed-sapping wings that give its race relations their downforce.

Says Palmer: "It hasn't got much downforce compared with a sports car or a grand prix car, but for a road car, it has a lot. Even in racing terms it's still very, very quick ... probably quicker than a Group C car in a straight line because the drag is so low."

He pauses, considers what he's about to say, then delivers it matter-of-fact:

"It actually feels like it accelerates faster, from 150 miles an hour up, than any other car I've ever driven ... "

Jonathan Palmer has driven plenty of GP cars. Still more Group C machines.

Think of the fact that the F1, fresh out of the box and on road tyres, matched the slick-shod XJ220 racer around Silverstone. Think also of 0-100 km/h in around 3.2 seconds, standing start to 160 km/h in under seven.

Road cars, no matter how fast or uncompromised, never feel quick on a race track. There's something about the wide open space of run-off areas and the freedom of having a whole track to use that seems to make them slog.

Not the F1. It's far, far more in line with Formula One levels of performance than it is with supercars, especially in terms of subjective feeling. Yet the bespoke CD player is capable of faithfully reproducing Blonde On Blonde while the chassis pulls 3G. We came to Silverstone sceptical. We came away awed.

It looks noticeably quick, this car. Quick in a way that no road car I've ever seen on a track has ever done. Part of that is the sound. From the outside it's not the primal bark of a modern grand prix car. (McLaren's MP4/7 was at Silverstone alongside the F1 to compare) more the high-tensile, shear-whine of a turbo-prop aircraft buzzing the ground beside you.

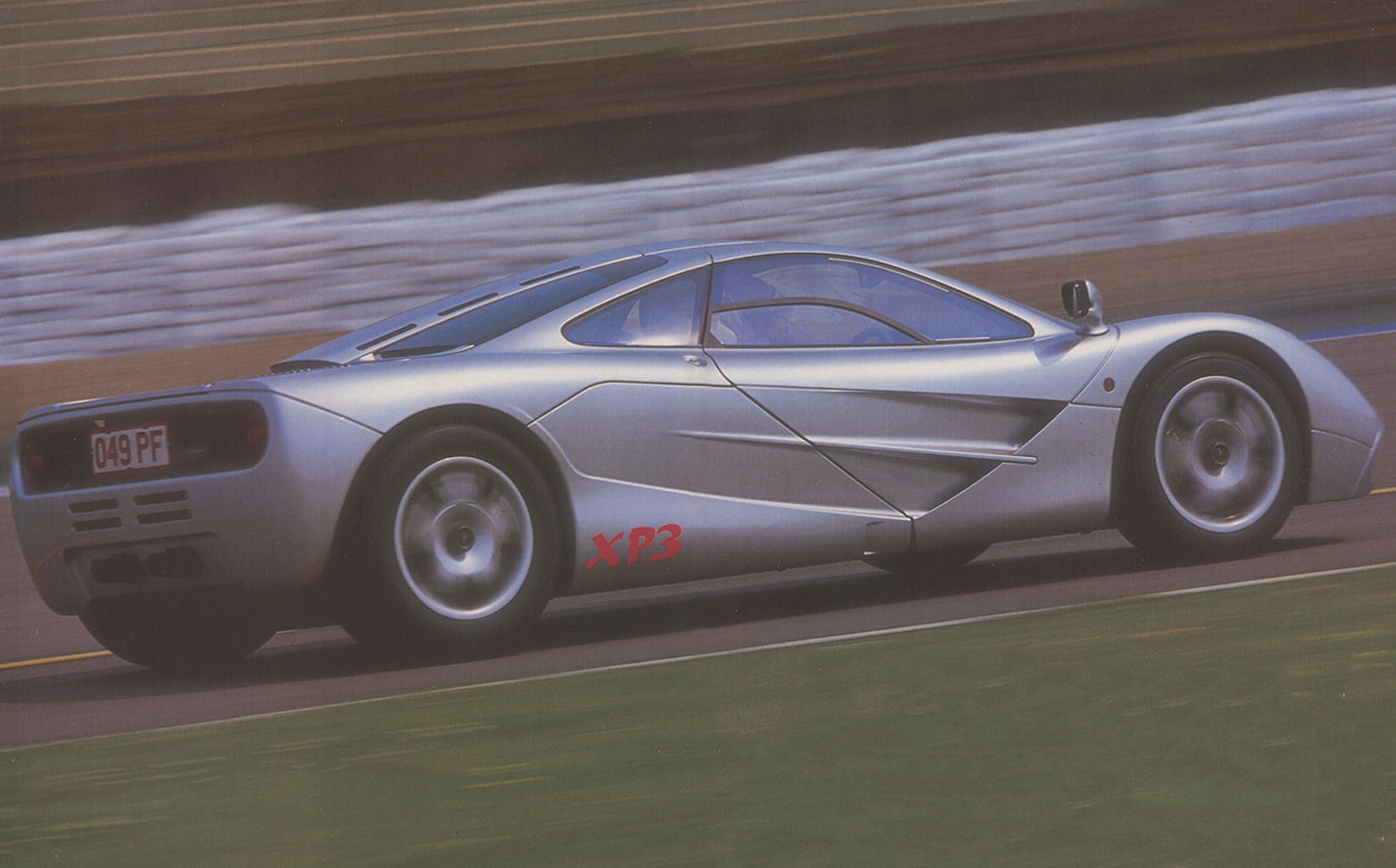

Inside? Another story, another world. This is XP3, the third running experimental prototype to be built and one of a £1 million brace, XP1 having been destroyed in a 265 km/h accident while hot weather testing in Namibia.

XP3 is McLaren's development car; its sister is the ward of BMW, the supplier of the Paul Rasche-designed 6.1 litre V12 that bowled me over with its voice, its tractability and its brute power.

McLaren's work with XP3 at Silverstone is essentially chassis work, fine tuning the ride ("the most work to do," according to its creator, Gordon Murray), brakes ("90 per cent there already") and handling ("very close, surprisingly").

But there are other things still to be done. It's an indication of his commitment to the tiny details - and, by association, the entire project - that the day before, Murray, McLaren Cars' technical director and the inspiration for the F1, had been at MIRA testing the F1 's CD player's resistance to G-force. Murray and Creighton Brown (McLaren Cars' commercial director and a highly rated club driver) aside, the chassis development work has been carried out by Mika Hakkinen, the grand prix team's ex-Lotus laddy in waiting, and our chauffeur, retired grand prix and sports car ace Dr Jonathan Palmer.

Palmer these days makes a Mercedes S class living from organising - and providing the thrills at - corporate hospitality events and from testing McLaren race and road cars. So he turns up looking client-meeting smart ... and leaves with stripes of perspiration showing on his shirt where a four-point harness strapped him in that central driving seat.

F1 etiquette means that you can't get in until the driver does, so while Palmer's on the phone there's a chance to look over XP3. Gone are the first car's A-pillar mounted wing mirrors and indicators. Instead there are bigger wing mirrors on the highest points of the fenders and new indicators set in the nose below the lights. "Mounting the indicators there made the nose look just too busy so we're going to take the spot-lamps out of the air intakes. It looks good, a lot more aggressive," says Peter Stevens, who designed the F1 exterior just as he did the Lotus Elan's.

XP3, still sporting a few aluminium panels as tooling is finalised for the finished composite versions, doesn't look like a development car. The hi-fi, the air-conditioning, the conductive anti-fog glass, the pop-up foil that's key to the active aerodynamics and brakes, all work. And the cockpit looks very inviting.

Palmer, ready to go now, crouches down, drops his bum onto the edge of the front seat and swings his legs in. It doesn't look difficult. He's got his belts on before I climb in on his left away from the six-plus-reverse shifter. With Palmer sliding his seat a little way forward, I can chat with him easily now that the overhead air intake's 'downpipe' has been moved backwards and out of the cabin.

The first thing you notice sitting in the cabin is not so much the position of the seat (Palmer's head is about 30cm in front of mine) but its angle of recline. You fall back into it, like a baby in a cot, and it feels odd until you realise that it's the same angle as the driver's. You're afforded the same view thanks to Stevens and Murray deciding on a layout that makes sure you look inside the A-pillar. Back seat drivers never had it so good.

"We tried a dummy set-up with the seats wider spaced and the screen pillars closer together," says Murray, "but people didn't like it. It made them feel like they were sitting outside the car." Inside the car I've sat back and, just as Ron Dennis, McLaren's owner and the man who rubber stamped this entire project, predicted, felt the entire length of my back take the weight of my body, with my bum facing forwards ready to take all that the 332 mm monoblock Brembo brakes could throw at me. I'm making do with a three-point harness but it doesn't bother me - this is an extremely snug (don't read that as claustrophobic because the F1 is anything but) motor car.

Dennis, smiling from ear to ear and telling me I was lucky to get the inside seat, closes the scissor door on me. It's a tight fit. My face is just inches from the trailing edge of the small opening in the window and there's not too much room for my left arm. There's no problem with my feet through, which barely reach the newly carpeted carbon fibre bulkhead (I'm 173 cm). When Palmer starts talking it's simply a question of leaning forward to get face to face with him.

"It's like being in a grand prix car," he says, immediately picking up on the theme for the day. But, like everything Palmer says, it's worth listening to. "You get all this wonderful panoramic vision, but you get none of the turbulence." He adjusts the interior mirrors, checks the other two on the fenders, tightens the belt and as I'm half expecting a raised arm to signal the engagement of an air starter, he turns the ignition key, flips the cover off the red button in front of the black wood shifter and presses.

The Series II BMW engine fires instantly. Its voice is healthy but lean. It doesn't hunt or pop or race, but there's anticipation in its complexity. Anticipation, in this 24-injector version, of 433 kW and 603 Nm delivered at near peak revs of 7300 rpm. I'm just examining the rev counter bang in front of JP (zero rpm is about four o'clock on the dial, the 7500 rpm deadline at noon), when Palmer blips the throttle, goes back and to the left for reverse and backs out of the pit garage. He's talking again.

"It's not just about power, this engine. There's staggering flexibility, too." To make the point he accelerates to about 24 km/h in first (about 2000 rpm) then goes right across the stubby little gate to sixth, re-engages the medium weight clutch and drives on. The engine doesn't give a monkey's. It keeps pulling and would keep doing so, had it the space to run to 350 km/h and beyond.

Even on Silverstone's narrow connecting roads Palmer's blipping the drilled pedal, dipping his toes into the 6.1 litre's honey-pot. And with it - but only for an instant, so quickly do the revs rise and fall of this aluminium flywheeled V12 - is the BMW's howl of exertion.

Out on the road there's little time for extended exposure to high terminal speeds and, with the BMW redefining responsiveness, our quick blasts round the speedo come and go quicker than you'd notice. There is time to appreciate, by proxy, the F1 's traction and handling. Its wheels only ever spun in first, so four-square does it address the road. Palmer's skill makes our exit from roundabouts a beautiful four-wheel drift.

Palmer, who will stick with McLaren throughout development, then run the driver training program it will offer to buyers, is clearly entranced by the car.

Out on the circuit Palmer goes into controlled attack mode, braking (but only just) for Stowe at 280 km/h. Fully sorted, he reckons 300 km/h would be easy.

His lap is one of extremes, whether flat round Copse in fifth, or slip-sliding through the new complex as he constantly alters the F1’s attitude with intensive throttle modulation.

"You couldn't do that in an F40," he was to say later, "you either spin off or understeer off. The F1 just understeers mildly, then you decide what to do. You can play tunes on this throttle."

Palmer's music making is cut short by the failure of a gearbox oil seal. The test session is cut short. There's a lot of work still to do. New production director and ex-Lotus Elan troubleshooter Derek Waeland has estimated that XP3 is only 20 per cent of the way there.

There's more to be done on the ride with Bilstein, although only the high piston velocity stuff - big ridges and dips. The chassis will be returned to give a little more oversteer, and there's a decision to be made on how much of that noise should be removed from the cockpit - the current favoured solution is to offer three levels of sound proofing.

But the car, essentially right out of the box, will take its drivers closer to grand prix speeds than they could ever have imagined. Yet at the same time its tractability, sensible ratios, air-con (Palmer was the only sweaty one at Silverstone), and the sheer efficiency of the car (they talk about 14 L/100km at McLaren) means it's no temperamental brute that only puts a smile on your face once a month. If Palmer's exuberance is anything to go by, you're never likely not to enjoy the F1.

Ron Dennis explained why the F1 is embellished by none of the systems his grand prix cars have; no anti-lock brakes, no traction control, no active ride, no semi-automatic. "The F1," he says, "is all about the sheer pleasure of knowing that what's doing it right, is you."

Protect your Classic. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.