Renault 16: Régie hatches a radical new approach with sweet 16

No question, the Volkswagen Golf GTI is regarded as the pioneering hot hatch. But half a dozen years earlier a very different kind of car ushered in a new way of thinking about the melding of high performance and functionality. This car was not as rorty, agile or racy looking as the GTI but it was more radical in concept – if you forget the ‘hatch’ bit, the Mini-Cooper S was the first pocket rocket.

When we think ‘hot hatch’, we don’t think Renault 16TS, but we probably should.

Hot hatches – the Golf GTI, the Renault 5 Turbo, the Peugeot 205 GTI, the Suzuki Swift GTi, and so on – are rorty and overtly racy, often with red highlights either outside, inside or both. They have sweet-shifting floorshifts, a firm ride, sharp steering and a brilliant power to weight ratio. The 16TS, by contrast, had a column gearchange, cosseting ride accompanied by copious body roll and no element of boy racer decor. But its rack and pinion steering was superbly direct and full of feel, and the number of brake horsepower per kilogram of weight was none too shabby.

OK, let’s call it instead the world’s first sports hatch.

The GTI was a tweaked Golf and the 16TS was a tweaked Renault R16, which had been launched three years earlier in 1965. I am not going to be silly enough to claim to the (highly knowledgeable) Shannons Club that the R16 was the world’s first hatchback but it was probably the first to be described as one, albeit subsequent to its debut. It seems that in 1965 the term was not in widespread use. I have seen the 1961 R4 retrospectively described as the world’s first mass-produced hatchback but, believe me, no-one ever called it one when it was current.

Renault’s own publicity proclaimed the R16 to be a ‘limousine’, while the reviewer for the English publication Motoring Illustrated, wrote (slightly ungrammatically) in the May 1965 edition:

The Renault 16 can thus be described as a large family car but one that is neither a four-door saloon and nor is it quite an estate. But, importantly, it is a little different.

No, you couldn’t call it a beautiful car but the rear three-quarter angle on this Sun Yellow TS shows a certain elegance born of supreme functionality.

A little different? I can’t remember how long after I bought my first Renault 16TS in 1973 I tested its camping credentials, but I suspect not long. You slid both front seats right forward, then folded the backrests flat for a passably comfortable bed. Or you could turn your sports sedan (hatchback) into a spacious van by folding the cushion of the rear seat forward to rest against the backs of the front seats and suspending the backrest by hooks to the grab handles in the roof.

The hatchback design liberated a van-like capacity to swallow suitcases. Compare this with, say, a Holden HQ Premier with the spare thrown onto the floor of the boot as if randomly!

Doubtless later safety legislation would have made such simple practicality illegal. A Renault advertisement detailed six alternative configurations: ‘Full cargo’ luggage position, ‘Play-pen’ position, Holiday luggage position, Rally resting position, Extra-bulky luggage space, Fully reclined position.

This idea of a fifth door opening into a versatile luggage area seems so obvious you have to wonder why this cross between a conventional three-box sedan and a wagon wasn’t brought to reality earlier. Even more to the point, how impractical the Renault 16 made some later cars seem. Why, for example, did the hatchback-shaped Lancia Beta have a normal boot and surely it would have been easy to engineer the Alfetta GTV’s rear window to lift with the bootlid?

The Renault 16 went on sale in Australia in 1968, this particular example in Victoria.

Like the Renault 10, the 16s all had brilliantly comfortable and supportive front seats. The TS added intriguing new features such as a heated rear window and a tachometer which was still not to be taken for granted in a sporting model of 1969. The Datsun 1600 didn’t have one, while the Fiat 125 in time-honoured Fiat fashion used dots on the tachometer to suggest the maximum speed for each of the lower three gears.

Unlike perhaps its closest rival, the aforementioned Fiat 125, the hottest 16 did not employ overhead camshafts, not even a solitary one. But its Gordini-designed cylinder head featured hemispherical combustion chambers. Peak power arrived at 5700rpm. Taller gearing than the 125 and that plush ride made the Renault the preferred choice for interstate tripping, even if the Fiat was maybe 0.3 of a second quicker through the quarter mile and undoubtedly the superior weapon for Mount Panorama (where its four-wheel disc brakes showed to advantage over the 16TS’s disc/drum configuration).

This is an early Renault 16 interior with unfortunate faux timber.

I was starstruck by the 16TS from the first time I looked at it closely in 1972. A friend’s doctor father had already covered some 96,000 miles in his within three years. Back in the early 1970s, we still expected engines to wear out, unless you had a Peugeot 404. This, at least, was what I believed. You’d hear of the occasional EH Holden getting to 100,000 miles without having at least the head done but expectations were closer to 80,000. So I could hardly believe that this quiet but interesting looking Frenchmobile was not on in imminent need of an engine rebuild. I followed its history for a couple more years and many thousand miles and it was still going strong in someone else’s hands the last time I heard.

So I became focused on getting my own 16TS as soon as I could. At the time I drove and enjoyed an 1970 Austin 1800 Mark II but the performance was nowhere near as strong. Towards the end of 1973 I got my chance and bought a 30,000-mile white 1970 16TS (Victorian rego KNX 256) from Renault Australia for $2350. It remains one of the best cars in its own context of time that I have ever owned. During the 1980s I owned another three.

There was, however, a certain frangibility to these cars. The front end would gradually sag on its torsion bars. The glass coolant overflow bottle in my first car exploded one night. Servicing and insurance were expensive. Rust was a serious issue as the cars aged.

Other innovations included a longer wheelbase on the left (107 inches) than the right (104) as a weird consequence of the torsion bar suspension. Also, the spare wheel was mounted beneath the bonnet which could be locked externally with a key. Watching a 16 for the first time you could almost think it had hydro-pneumatic suspension, courtesy of deadly rival Citroën. With the parking brake on, when reverse gear was selected, the rear of the car rose several inches. Vive La Différence!

The standard Renault R16 (in Europe all Renault models had an ‘R’ preceding the number, thus: R4, R8, R10, R16, R12, etc) was European Car of the Year for 1966, which was only the third year the award – voted on by European motoring journalists – had been given. (In 1964 the Rover 2000 beat the Mercedes-Benz 600 and Hillman Imp. In 1965 the Austin 1800 was first, the Autobianchi Primula second and the Ford Mustang third. The R16 beat the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and Oldsmobile Toronado.)

In 1970, by which time the R16TS was making a great name for itself, Stirling Moss said:

There is no doubt that the Renault 16 is the most intelligently engineered automobile I have ever encountered and I think that each British motorcar manufacturer would do well to purchase one just to see how it is put together.

The R16 was Renault’s second front-wheel drive model, the first having been the charming little R4 in 1961. In some respects the R4 set the template for the much bigger R16, which became the eventual successor to the slow-selling rear-engined Fregate (1951-1960).

Following World War Two, Renault was nationalised as the Régie Nationale des Usines Renault: friends called it Régie Renault, or just The Régie. The first postwar car, the preliminary work for which Louis Renault had done before he died in 1942 and which entailed direct personal input from Ferdinand Porsche (designer of the Volkswagen Beetle) when he was invited to examine drawings of the forthcoming model, was the 4CV.

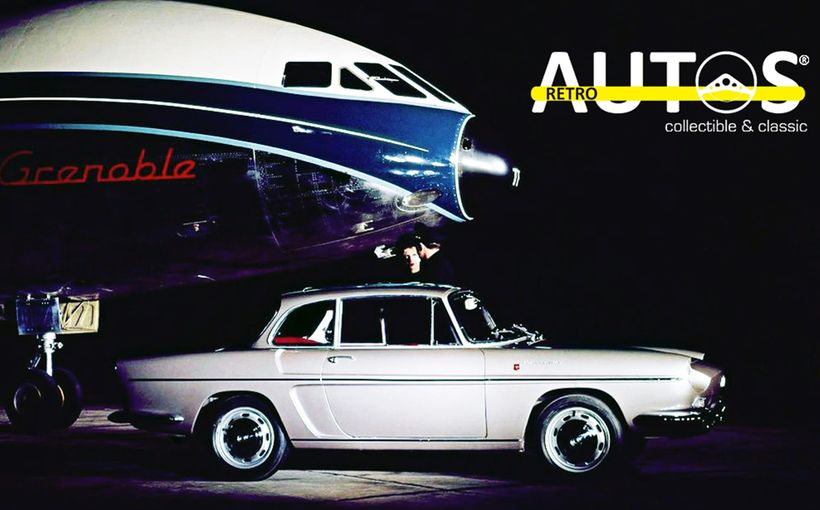

Throughout the 1950s The Régie continued to follow the proven Volkswagen approach of rear-engine/rear-wheel drive. In 1955 the pretty little Dauphine made its debut and the gorgeous Floride (soon to be renamed Caravelle) coupe and cabriolet arrived in 1958, by which time the Dauphine was going gangbusters in the US. The idea for this chic Renault came to Pierre Dreyfus, President Director-General of the Régie from March 1955 (after his predecessor, Pierre Lefaucheux, was killed when his Renault Fregate rolled and his suitcase struck him in the back of the head) and a group of executives. They were at a dinner at the home of the Governor of Florida when the idea of a small sporty model was conceived: hence ‘Floride’. But inter-state rivalry in the US forced them to come up with a new name.

Renault design was about to bifurcate in a curious fashion. The idea that materialised as the Renault R4 was Dreyfus’s, coming while he was reading a newspaper story on projected French demographics. Illustrations showed various family combinations. ‘Next to each picture I imagined a suitable car,’ said Dreyfus. ‘My approach to the automobile has never been technical, always sociological.’ The R4 (Project 112) was his first Renault. The next was Project 113, where (which never eventuated because the car would have been too expensive) was for a large car to replace the Fregate. Project 114 was where the Renault R8 grew longer front and rear overhangs and acquired extra refinements to become the R10. Project 115 was developed instead of 113. If ever a car was a consequence of devotion to sociology before technology, the Renault 16 was it.

This colour was called Sunburst and was very fashionable in 1969-70.

Meanwhile the R4 (which became the third top selling car in history, behind the Beetle and the Model T) was in its way as radical in 1961 as the Issigonis Mini had been two years earlier. In some sense this tiny van was Renault’s belated response to the Citroën 2CV, but it makes more sense to compare it with the 1934 Traction Avant, which also featured a front-mounted transmission, column shift and torsion bar suspension: it was as if, three decades on, the Régie finally paid his tribute to André-Gustave Citroën. It is almost impossible to credit that the urbane 16TS can trace its engineering ancestry back to the R4.

Because the R4’s gearbox was right out front, the car could have a flat front floor (with the linkage passing over the engine). There was a dash-mounted gearchange. Initially at least, the R4 used a three-speed transmission lacking synchromesh on first. What a far cry from the ultimate version of the R16, the 1973 TX, which sadly never came to Australia. It had a five-speed gearbox with synchromesh on all ratios and a column shift.

The R16 arguably had more design elements in common with the humble R4 than it did with the R12, which arrived in October 1969 and had the engine – still longitudinally mounted – ahead of the gearbox. The R12 also had a floorchange and was generally less radical in both character and styling than the more expensive R16.

What remarkable times these were in automotive history. Front-wheel drive was nearing its cusp of orthodoxy but there was still to be a decade and a half between the Australian launch of the 16TS and the time when drive to the rear wheels for cars of this size and larger remained the norm. Consider the variety of products offered by Renault. In 1970 a friend of mine bought a brand new Renault 10S – amazingly, the standard R10 was released in Europe six months after the R16! I drove it at highish speed down the Geelong Road and found it every bit as hairy in crosswinds as the 36-horsepower 1960 Beetle I had recently sold.

By this stage the fabulous 16TS had been on the Australian market for more than a year. So you could choose between a rear-engined Renault and a front-engined Renault, cars that could hardly be more different from one another – one that loved oversteer, one that displayed hefty torque steer in low gears climbing loose-surfaced gradients; one looking back to the early postwar era, one looking forward towards the time when the Volkswagen Golf – reinforced in Japan by the Mazda 323 – rewrote the formula for small cars, almost as different from the Beetle and the old Mazda 1300 as you could imagine. Despite this, the 10S and the 16TS were unmistakably products of the same manufacturer, determinedly French, implacably Renault.

It now seems that Renault was essentially running more than a half a decade ahead of Volkswagen, who would make the big shift to front-wheel drive with the 1973 Passat.

The TS arrived here in April 1969, 10 months after the standard 16 (no ‘R’ prefix in Oz). Both were assembled locally in West Heidelberg alongside Peugeots. With just 55 brake horsepower from 1470cc, the 16 was a little underdone in the performance department, slower than the Peugeot 404, for example. Early TSs had gorgeous Jaeger instruments but increasing local content saw these swapped for VDOs items. Some other minor downgrading of specification occurred. The TL replaced the standard 16 in 1971. This car used the TS’s 1565cc engine but with the head from the 1470cc unit. An automatic transmission of Renault’s own amazingly complex design was made available. The TX, introduced at the 1973 Paris Show, got a 1647cc engine, quad rectangular headlights, cloth trim, the aforementioned five-speed column shift (a world first, Shannon Club members?) and some other extra kit.

The TX was highly desirable to those already sold on the merits of a 16.

In summary, I think the renowned author Jean-Francis Held assessed the 16 precisely when he wrote:

Renault has launched a pure automobile idea on to the market…Renault 16 is not a station-wagon; it is a synthesis of a station-wagon with a saloon, relying on the former’s advantages to overcome other saloons, yet retaining the advantages of a saloon sufficiently to outsmart other station-wagons.

Renault, proclaimed Held, created cars out of the public’s unconscious desires. Where some cars like the BMW X6 appear to represent an answer to a question no-one asked, the Renault 16 was the brilliant answer to a question few people had even begun to consider. Vive la difference!

The 16TX looked absolutely comfortable in Paris. What a pity Aussies never got the chance to buy it.