Volvo 240: From Safe Swede to Turbo Terror!

If there was ever a car that embodied the personality contrasts of Dr Jeckyll and Mr Hyde it was the Volvo 240 Turbo and its alter ego Group A Evolution. Designed without compromise for outright success in Group A touring car racing, its astonishing performance resulted in championship wins in Europe and Australia and changing perceptions of the staid Swedish brand.

The ‘Evolution’ certainly lived up to its name, as it evolved from the 200 series range which was widely maligned largely due to Volvo’s apparent obsession with crash safety to the exclusion of many other desirable design and performance attributes.

This unassuming race car was based on the 240 Turbo model which Volvo had introduced in 1981. The 2.1 litre turbocharged SOHC four cylinder was claimed to produce 155 bhp and propel the brick-like rubber-bumpered sedan to 100 km/h in 9.0 seconds and a top speed of just under 200 km/h. It was hoped the blown Swede would attract a new type of ‘sporting’ buyer.

As unlikely as it may have seemed the 240 Turbo was in fact ideally suited to new international Group A touring car rules introduced in 1982, which presented a tantalising opportunity for Volvo to take on the best in the business - and win.

Victory in the 1985 European Touring Car Championship, 1985 German Touring Car Championship (DTM) and the 1986 Australian Touring Car Championship along with many other successes proved that the Swedes were spectacularly correct!

How they pulled it off is an intriguing story. And one not without controversy, which would lead to Volvo’s untimely withdrawal from the sport when at the top of its game.

The first Volvo 240 Turbo to compete in a round of the ETCC was entered by Sweden’s Sportpromotions team in the 1982 RAC Tourist Trophy at Silverstone. Volvo hosted a domestic one-make ‘Cup’ series for the 240 Turbo in Sweden that year, so this car remained largely in that mildly modified specification in the TT. It failed to finish the 500 km race, but they had to start somewhere. Image: www.tentenths.com

1982-1984: The birth of Group A and Volvo’s Turbo Warrior

In a nutshell, Group A stipulated that a mass-produced passenger car had to be manufactured in a minimum number of 5000 units a year to be eligible. The rules also allowed for ‘sporting evolutions’ of that base model, if the manufacturer built at least 500 for public sale and road use.

Group A was designed to foster close competition amongst a wide variety of global makes and models by using a clever sliding scale that matched a car’s cubic engine capacity (cc) with a maximum fuel tank size (litres), tyre width (inches) and minimum weight (kg).

For turbocharged engines, a modest equivalency factor of 1.4 was applied (base cubic capacity x 1.4 = total cubic capacity). This power-to-weight ratio formula was excellent in its early guise, when turbocharged engine outputs were modest (not for long!) and the equivalency factor between turbo and non-turbo engines had some relevance.

In addition, engine modifications were limited so that performance remained as originally calculated. These restrictions included using the standard inlet and exhaust manifolds, valve size and lift (although valve lift restrictions were relaxed for 1986). Car builders had their pick of specialist after-market suppliers for things like pistons, valves, camshafts etc.

Early days for the Volvo 240 Turbo in Group A proved that it would need more power to be competitive. Here one of two Swedish-entered 240 Turbos is seen during practice for round three of the 1983 ETCC at the UK’s Donington Park, where both cars failed to qualify. Planning for the faster ‘Evolution’ version was already well underway. Image: www.flickr.com

Suspensions could be improved for racing provided the design and factory mounting points were unchanged. Common sense also prevailed with brakes, gearboxes and diffs which were free, provided they were homologated by the manufacturer.

On the face of it, these engineering freedoms were mainly designed to improve durability under the rigours of competition. Not surprisingly, Group A was immediately adopted for the 1982 European Touring Car Championship.

Although Volvo was not officially involved in that first ETCC run to the new rules, the company did lodge homologation papers for the 240 Turbo Group A which were validated by controlling body FISA from March 1, 1982.

A privately entered 240 Turbo did make a surprise appearance at the ‘Tourist Trophy’ ETCC round held at the UK’s famous Silverstone circuit that year. Although far from exploiting the limits of the new rules, the Sportpromotion-entered car showed promising potential for Group A development.

In 1983 Sweden’s Thomas Lindstrom Racing competed in the ETCC with a 240 Turbo and enjoyed some early success. However, It was clear that the car would need more power to be a genuine championship contender and that could only be achieved with direct factory involvement.

After determined lobbying, Volvo management could see the odds were stacked in their favour and Volvo Motor Sport (VMS) was established to supply race cars and parts to its nominated race teams. With this commitment also came the decision to produce a ‘sporting evolution’ of the 240 Turbo in a one-off batch of 500 cars, equipped with all the hot bits Volvo needed to beat outright pace-setters like the Jaguar XJ-S, Rover 3500 SD1 and BMW 635 CSi.

A larger turbocharger plus intercooler, water injection and a big rear spoiler were considered essential to allow a boxy Volvo sedan powered by a 2.1 litre four cylinder engine to mix it with non-turbo V12, V8 and six cylinder rivals boasting much larger engine capacities.

A breakthrough Group A win came in the penultimate round of the 1984 ETCC at Zolder in Belgium, when the Swedish driver pairing of Ulf Granberg and Robert Kvist took the chequered flag in their Sportpromotion 240 Turbo Evolution. The car which claimed that historic first win is still competing successfully in historic touring car racing in Europe. Image: www.ultimatecarpage.com

Volvo 240 Turbo Group A Evolution

Based on the two-door body shell shared with the 242 GT, the 240 Turbo Evolution just snuck in under the 3.0 litre engine limit when the turbo equivalency formula was applied. This allowed a minimum weight of 1065 kg which was more than 100 kg lighter than the 3.5 litre Rovers and BMWs – a considerable advantage.

Aluminium or carbon-fibre panels were forbidden. So was acid-dipping, although much harder to prove. It’s believed that at least some of these body shells from VMS spent time in the acid bath to eat away some excess steel. Door frames and other components were also acid-dipped while door skins, bonnets and boot-lids were stamped from lighter gauge steel. Thinner window glass, plastic headlights and a lightweight aluminium roll cage all contributed to this drastic weight loss.

The rear wheel housings were enlarged to fit wider racing wheels and tyres (relocation of chassis rails was rumoured) and the boot fitted with a 120-litre fuel tank with dry-break fillers. Interestingly, it’s claimed that all Group A racing Volvos from 1982 to 1986 ran with the 1982 model’s flat bonnet, grille and surrounds as they created the least amount of aero drag.

The Evolution’s engine was based on the standard 240 Turbo’s B21 ET 2.1 litre SOHC four. Although as previously mentioned this small base cubic capacity was rewarded with a lower minimum weight than its outright rivals, the Volvo was also restricted to a 10-inch wide tyre compared to 11s for the Rovers/BMWs and 13s for the big V12 Jaguars.

Cutaway shows the huge amount of work required to turn a humble Volvo sedan into a Group A champion. Note how the rigidity of the unitary body shell was greatly increased by the roll cage, constructed from numerous lengths of lightweight aluminium alloy tubing joined by spherical rod ends. Note also the on-board pneumatic jacking system which instantly raised the car for tyre changes during races. These systems are very common today. Image: www.carsperformance.net

The Volvo race engines used only the best gear including stronger cylinder blocks, forged steel cranks and rods, Mahle 7:1 forged pistons, racing camshafts and heavily baffled wet sumps (dry-sumps were not allowed). The SOHC type 531 or 405 eight-valve aluminium heads were cast from a special alloy and ported to the limit of the rules.

A Garrett T3 turbocharger pumped about 1.5 bar (21-23 psi) of boost through a large aluminium intercooler. This resulted in a neck-straining surge of power from around 3000 rpm to 6500 rpm with a 7500 rpm redline. Exhaust gases were dumped through a big 3.0-inch open exhaust pipe that finished under the passenger door.

Great attention was paid to thermal efficiency, as the extreme temperatures created by turbochargers can cripple engine performance and reliability. Special high volume water pumps were used and the water jackets reconfigured to increase cooling capacity and efficiency. They used huge radiators with twin thermo fans plus separate coolers for engine oil.

Volvo was one of the first to master the science of electronic engine management in racing. A Bosch K-Jetronic CIS (Continuous Injection System) provided precise control of fuel and ignition curves along with a second ECU called WT (Water, Turbo) which controlled turbo boost pressure and anti-detonation via sequential water injection.

Success! The combined expertise of Volvo Motor Sport and Eggenberger Motorsport proved a winning formula, when Italian ace Gianfranco Brancatelli and Swedish Volvo loyalist Thomas Lindstrom won the 1985 ETCC in their 240 Turbo. The ETCC races were long (500 km) and required at least two drivers per car, so finding the right combination was crucial to success. Image: www.media.volvocars.com

Injecting a cocktail of water and methanol was one of the key factors in the success of supercharged fighter planes in WW2, as it stabilised the high pressure combustion process to minimise detonation and increase power. Former Volvo team owner Mark Petch (see The Australian Connection) claims that the Volvo system only used pure water with a small portion of cutting fluid to avoid rust on the injectors.

Volvo and the RAS Sport team also experimented with traction control late in 1986. The system used sensors to measure the speed of the front and rear wheels. If the rears started to spin, the turbo boost and fuel supply were reduced until the front and rear wheel speeds equalised. Although it was highly effective and produced faster lap times in testing, it was never used in a race.

Early Volvo Group A engines had about 250 bhp but by 1986 the full-house ‘Evo’ engines were claimed to be producing up to 380 bhp at 6600 rpm, which was more than rival 3.5 litre V8 Rovers and six-pot BMWs and not far off the 4.9 litre V8 Commodores.

Bountiful torque of 420 Nm was on tap from around 4000-5500 rpm, which put the narrow 10-inch wide tyres under considerable stress trying to get all that grunt to ground without erupting into frantic wheelspin. With the right gearing these hot turbo fours could propel the boxy Volvos to phenomenal 270 km/h-plus top speeds on fast, big power circuits like Monza, Silverstone and Hockenheim.

The Volvo 240 Turbo could not defend its ETCC title in 1986, despite unrelenting technical development by VMS and RAS Sport plus a star-studded driver line-up including 1985 ETCC winner Thomas Lindstrom and former world motorcycle champ Johnny Cecotto. Image: www.lemans-models.nl

The rest of the 240 Turbo Evolution was equally robust, with a Getrag five-speed gearbox equipped with an oil cooler and hardened gears to cope with the turbo’s big torque loads. An AP competition clutch fed the power to a lightweight live rear axle assembly featuring bolt-on axle tubes that created 1.5 degrees of negative camber on the rear wheels. A Dana-Spicer or ZF limited slip diff with oil cooler, a huge choice of ratios and 30 percent lock-up (to reduce slow corner understeer) meshed with lightweight hollow-section axle shafts.

The fully adjustable front suspension comprised competition struts with Bilstein adjustable shocks, cast aluminium alloy lower control arms, quick-ratio power steering, adjustable anti-sway bars and single nut centre-lock hubs. Under the tail a fully adjustable four-link with panhard rod, Bilstein shocks, special springs and bars. By 1986 carbon fibre lower arms had been homologated which were claimed to be 60 percent lighter than stock.

To stop this turbocharged missile, Volvo specified Lockheed four-piston calipers clamping big 330mm vented front discs and smaller 280mm rears with driver adjustable brake bias. 16-inch and 17-inch diameter racing wheels up to 9.0-inches wide were fitted with a variety of tyre brands in the maximum allowable 10-inch width.

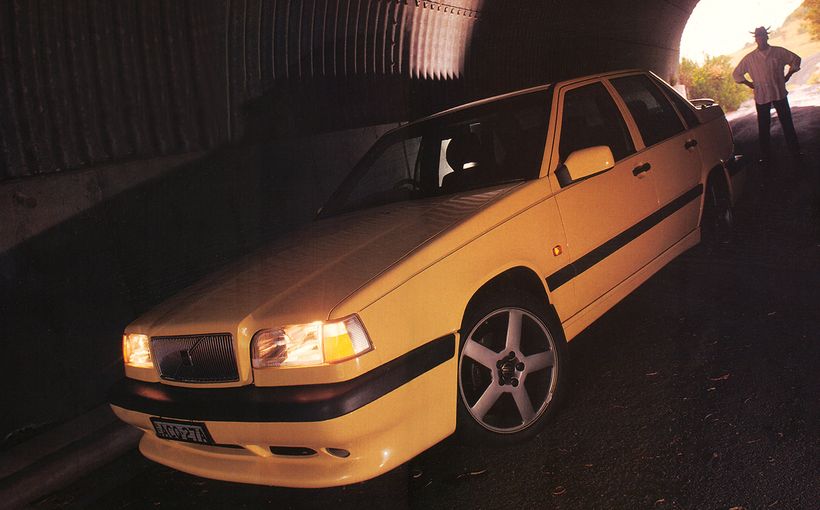

How the Volvo 240 Turbo Evolution looked in road-going form. Allegations that only a handful (if any) of these cars (instead of the required 500) were made available for public sale caused a huge political storm for Volvo and left a big question mark hanging over the legality of the race cars until the bitter end. Note the race-only centre lock wheel hubs. Not sure if your local Bob Jane T-Mart would have had the right rattle gun to undo these suckers! Image: www.touringcartimes.com

The Volvo 240 Turbo Evolution was shrouded in controversy. In a painfully long political saga, Volvo presented the minimum 500 cars required for homologation and the Evolution was approved by FISA in 1983.

However, as officials had closely inspected only 23 of those cars, stories began to emerge that the other 477 examples had been stripped of their hot Group A parts and sold as standard 240 Turbos. By July 1985 FISA was on the offensive, after it tried and failed to buy an Evolution in several European countries. It then demanded that Volvo immediately issue a list of the 500 Evolution owners, but when Volvo could not provide such evidence FISA announced that the 240 Turbo’s homologation would cease in September.

With its first ETCC title hanging in the balance at that stage, Volvo eventually produced a short list of a few Evolution owners in Sweden which was apparently enough to satisfy FISA and the ban was lifted! This episode was typical of the smoke-and-mirror homologations which plagued Group A from the start and contributed to its demise, but former 240T campaigner Mark Petch said Volvo had a solid legal footing:

"One of the least understood facts about the FIA's controversial 500 Evolution rule that Volvo successfully exploited, was that the FIA rule was very poorly drafted from a legal point of view. Volvo's legal opinion was that you did not actually have to build 500 evolution cars, but merely offer 500 cars with all the homologated parts contained in the car itself for sale. I have spoken to two original American purchasers of the so-called Evolution cars, and both of them said they were offered the Evolution parts as additional cost extras. One declined to purchase any extras and the other said he purchased the boot spoiler only. When the FIA (FISA) was threatened with a law-suit by Volvo, they quickly backed down and re-instated the homologation and that is indisputable fact."

In 1985 Kiwis Robbie Francevic and Mark Petch were the first to race the Volvo 240 Turbo in Australia. Their LHD example was one of two factory-backed cars that competed in the 1984 ETCC prepared by Belgium’s Guy Trigaux Motors (GTM Engineering). Here the car is powering through Murray’s Corner at Bathurst in 1985. With co-driver John Bowe the 240 Turbo was competitive in qualifying but failed to finish the race after a troubled run.

In any case, armed with its new factory race car, Volvo became directly involved in 1984 and by 1985 had expanded its ETCC campaign by contracting not one but two factory teams - Eggenberger Motorsport, under Swiss tuning ace Rudi Eggenberger and Sweden’s Magnum Racing.

The Swedish marque and its ‘flying bricks’ were genuine outright contenders that proved highly competitive against the works Rover and BMW rivals. After a hard-fought season, the Eggenberger Volvo driven by Thomas Lindstrom and Gianfranco Brancatelli had won six of the 14 rounds to claim the 1985 ETCC.

Francevic set up Volvo’s 1986 ATCC victory by winning the first and second rounds in his Mark Petch Motorsport 240 Turbo, which was the same LHD car the Kiwi drove in 1985. Here at Amaroo Park’s opening round, Francevic gets away smartly alongside pole sitter George Fury in the new turbo Nissan Skyline. The championship battle between these two drivers went right down to the wire.

Volvo returned to defend its European title in 1986 with the Belgian RAS Sport team and a star-studded driver squad. Although highly competitive the Volvos lost their hard-won ETCC crown, which went to BMW after a thrilling championship fight between BMW, Rover and Volvo that was only decided after the final round.

However, after three thrilling seasons, Volvo announced a global withdraw from touring car racing, citing impending changes to the Group A rules (raising the turbo equivalency factor from 1.4 to 1.7 which would have put the Volvo into a higher weight class) and ongoing disputes with the sport’s governing body. The Volvo Motor Sport division was closed down and with that decision, the 240 Turbo Group A Evolution also reached the end of the road as a factory race car. However, it did win several more championships in Scandinavia and South East Asia in 1987 and 1988.

Francevic on his way to a championship win in the final round of the 1986 ATCC at Oran Park. It was not a happy victory though, due to growing tensions within the Volvo Dealer Team. Francevic was driving the team’s second 240 Turbo, which was an ex-RAS Sport factory car built in RHD to test for any performance advantage over LHD on clockwise circuits.

The Australian Connection

Kiwi Robbie Francevic in his 240 Turbo won the 1986 Australian Touring Car Championship. As a result, Volvo became the first Swedish marque to win any major championship in Australian motor sport. It was also the first turbocharged car to win the title.

The Volvo campaign started in 1985 when NZ saloon car champ Francevic and his long-time friend and enthusiast Mark Petch found an opportunity to chase their dream of winning the ATCC when Australia and New Zealand switched to Group A rules.

Petch, who had built a thriving business in hydraulic seals, purchased a LHD ex-works team 240 Turbo Evolution direct from Europe to be run under the Mark Petch Motorsport banner. It appeared to be a shrewd decision after Francevic and beefy Belgian co-driver Michel Delcourt won the Wellington 500 endurance race on the car’s NZ debut, before it was shipped to Australia.

Although he missed the opening round, Francevic scored two round victories to finish fifth in the 1985 ATCC. It was a tough debut season as the Kiwis faced a near vertical learning curve and with only three crew members (including Robbie) to work on the car, resources were stretched and reliability suffered.

The 1980s Group A Volvo race cars used the 242 GT body shell as their starting point. Interestingly, several years before, a stock standard, road registered 242 GT running on skinny street radials competed in the 1979 Bathurst 1000 driven by racing veterans David McKay and Spencer Martin. Although criticised by many (including Peter Williamson on Racecam!) for being a mobile chicane, the Volvo had a trouble-free run to finish fifth in the 3.0 litre class and 20th outright. That put a cork in a few critics.

However, Volvo Australia could see the potential and thanks to some persuasive lobbying by Petch began to provide some unofficial ‘back door’ support. When Petch announced that he would not be funding another season, Volvo Australia purchased his car and equipment with a view to mounting a proper factory-backed, two-car assault on the 1986 ATCC funded by the Volvo dealer network with Francevic as lead driver.

Based at a new workshop in Melbourne, the Volvo Dealer Team recruited former HDT team manager John Sheppard, plus more full-time staff and the services of Australian Drivers Champion John Bowe. The Tasmanian had co-driven with Francevic at Bathurst in ‘85 and would join the ATCC battle by round four when the team’s second car was completed.

The switch from Mark Petch Motorsport to VDT wasn’t completed until the third round of the 1986 ATCC, after which tensions surfaced between Sheppard and Francevic that worsened as the season progressed.

The Volvo 240 series also distinguished itself in local rallying when the works-entered 244 crewed by Ross Dunkerton/Peter McKay/Geoff Jones finished a gutsy fourth outright in the 1979 Repco Round Australia Reliability Trial. Although plagued by broken shock absorbers and other problems throughout the two-week ordeal, the exhausted Volvo crew were only beaten home by the dominant trio of HDT Commodores.

It became clear from round one that the championship was going to be fought out between two men - George Fury in his new Nissan Skyline DR30 and Robbie Francevic in his Volvo 240 Turbo. Although by mid-season he was clearly being outpaced by the Nissan, Francevic’s dogged pursuit of points paid dividends when he finished a safe sixth to win the title at Oran Park’s final round.

Sadly, behind the popping corks and spraying champagne, the relationship between Francevic and VDT had deteriorated to such an extent that the Kiwi was given his marching orders soon after, missing out on drives at the Sandown and Bathurst endurance races in which the factory cars performed poorly. It was a bitter pill for Francevic to swallow after he and Petch had played such pivotal roles in getting Volvo to commit to such a program in the first place.

However, his feelings of abandonment would soon be shared by Sheppard, Bowe and the entire VDT crew when Volvo Australia announced in November 1986 that it was withdrawing from touring car racing, in line with Volvo Sweden’s decision to do the same. It was the end of a short but exciting era for Volvo in Aussie Group A racing.