Nissan R32 Skyline GT-R: When Godzilla Ruled The World

Given the clear superiority of Audi’s revolutionary all-wheel drive Quattro in dominating the World Rally Championship in the early 1980s, it was no surprise to see the same traction advantage being exploited in touring car racing before the end of that decade. However, the definitive example came not from Germany but from Japan in the form of Nissan’s R32 Skyline GT-R.

There’s no denying Audi successfully adapted its four-paw technology to circuit racing, with development of a V8 Quattro-based Group A tourer that won successive DTM (Deutschen Tourenwagen Meisterschaft) German touring car titles in 1990-91 against smaller and lighter domestic opponents from BMW (E30 M3) and Mercedes Benz (190E Cosworth).

However, Nissan’s version was more compact in all key dimensions include wheelbase, length, width and height. And although they shared similar minimum weights in stripped-out race trim, the GT-R’s twin turbocharged six cylinder engine was capable of staggering power outputs of up to 700bhp compared to 450bhp from Audi’s non-turbo 3.6 litre V8 (turbos were banned in DTM).

In other words, the R32 Nissan GT-R had no equal in all-wheel drive technology in touring car racing. It was the definitive global Group A weapon, blessed with a unique combination of superior traction and ferocious power that often made its rear-wheel drive opponents look like mere grid fillers.

No surprise then that it earned the monstrous nickname ‘Godzilla’. The GT-R obliterated the Japanese Touring Car Championship every year from 1989 to 1993 and hastened the demise of Group A in Japan. It also won multiple tin-top titles in the UK, dominated the production car class at Pikes Peak for several years and claimed the 1991 Spa 24 Hour race.

And in Australia, it enjoyed arguably its most meaningful and hard-fought success in Group A. Given the high quality of local Ford Sierra, BMW M3 and Holden Commodore rivals, the local factory cars prepared by Gibson Motor Sport for Jim Richards and Mark Skaife were unquestionably the toughest and fastest GT-Rs on the planet. In fact, they were so good that Nissan politely asked Gibson-san not bring his cars to race in Japan to avoid embarrassing their local efforts!

As a result, the GT-Rs dominated local touring car racing as well, winning the 1990 (shared with GTS-R), 1991 and 1992 Australian Touring Car Championships and the 1991 and 1992 Bathurst 1000s, the latter in controversial circumstances.

Creating Godzilla

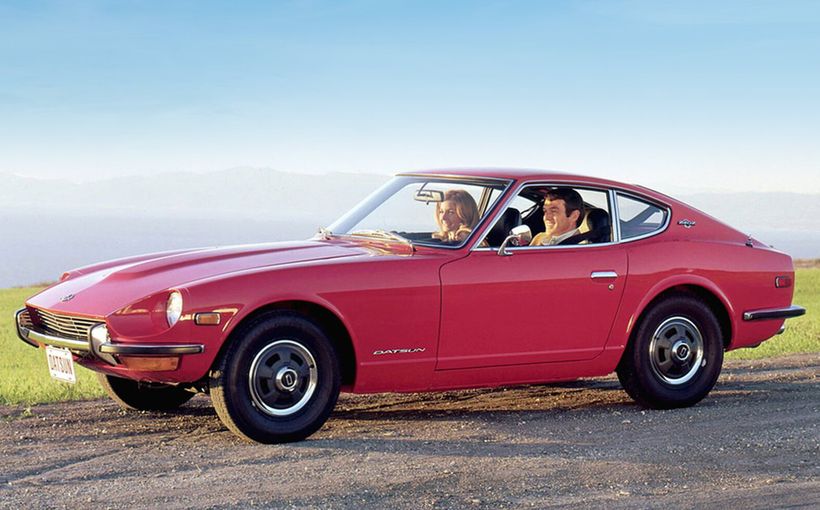

The first (C10) and second (C110) generations of the rear-wheel drive Skyline GT-R raced successfully in Japan from the late 1960s to the early 1970s until the world oil crisis forced Nissan to abandon the program. However, the concept of a stove-hot Skyline never died; it was just shelved for a while.

The catalyst to revive the GT-R came in the late 1980s. Nissan’s Skyline R31 GTS-R was finding life tough against BMW’s E30 M3 and Ford’s Sierra Cosworth RS500 under Group A rules, which allowed manufacturers to race ‘sporting evolutions’ of their base models provided they produced a minimum of 500 units that could be legally registered and driven on the street.

The problem for Nissan was that the BMW and Ford Group A weapons were effectively race cars detuned for road use, whereas the GTS-R was primarily a road car being used for racing with all the compromises that went with it. Not surprisingly, Nissan adopted the same philosophy as BMW and Ford when it came to designing a replacement for the GTS-R, but it went all out in its interpretation of the Group A rule book.

In true Prince Skyline tradition the engine had to be an inline six, relatively small in cubic capacity to minimise weight but capable of producing prodigious power by using not one but two turbochargers this time.

The original plan was for a continuation of rear-wheel drive. However by 1988 the turbocharged Ford Sierras were producing so much grunt that their 10-inch wide rear tyres were literally melting under the strain. Nissan engineers considered 500bhp to be the most power that a 10-inch race tyre could handle and given that Nissan would be chasing much higher outputs, the only logical solution was to go all-wheel drive.

The GT-R’s 4WD transmission, called ATTESA E-TS (Electronic Torque Split), was based on the system developed by Porsche for its Paris-Dakar winning 959 and built under license by Nissan in Japan. This wondrous, electronically controlled, all-wheel drive transmission with all-wheel steer capability (not used in racing) was equipped with three differentials – one at the back, another up front and a third in the middle.

In standard form, the third diff or transfer case optimally controlled via computer the engine’s torque distribution to the front and rear diffs according to driving conditions. Based on a rear-wheel drive configuration, this system could continually vary the front-to-rear torque split anywhere from 100 per cent on the rear to a 50 per cent share between front and back.

By automatically sensing the amount of rear wheel traction available and controlling the torque split accordingly, the GT-R’s ability to get huge power outputs to ground with leech-like grip would arm it with an immeasurable advantage over its rear-wheel drive foes - particularly on a wet track. However, as brilliant as it was, the all-wheel drive transmission came with a hefty 100kg weight increase.

After close examination of Group A’s sliding scale of minimum weights/tyre widths based on engine capacities, it was decided to aim the new GT-R at the 4001-4500cc division where its weight would be more comparable with rivals (minimum 1260kg) and allow a critical 1.0-inch increase in tyre width over the Sierras to 11 inches.

The engine chosen to power this missile was Nissan’s superbly refined 2568cc RB26DETT inline six with dual overhead camshafts, four valves per cylinder and electronic fuel injection. By applying the FIA’s turbo equivalency factor of 1.7 (2568cc x 1.7 = 4365cc), which was originally (and naively) devised to provide parity between turbo and non-turbo engines, it neatly slotted in under the 4500cc threshold.

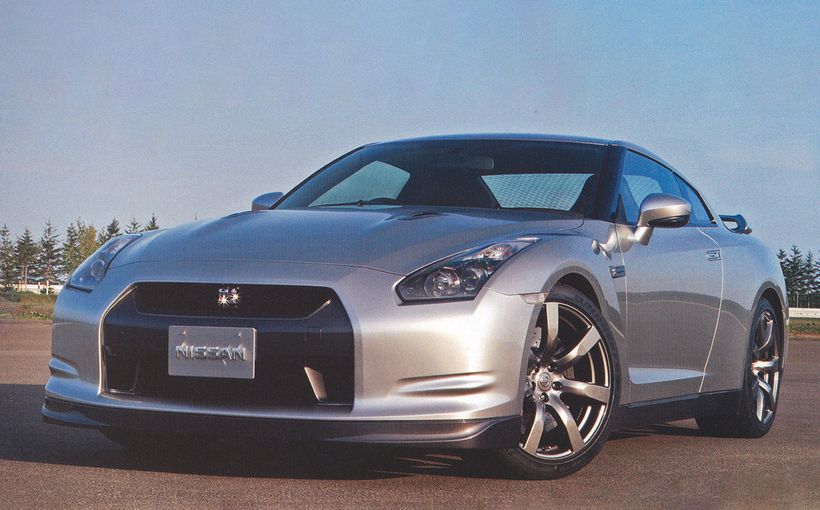

With final specifications locked in, Nissan committed to a production run of at least 500 sporting evolution GT-Rs or ‘homologation specials’ which laid the foundations for the race cars. Based on the R32 Skyline two-door hardtop, each was equipped with the 2.6 litre twin-turbo six with intercooler, five-speed manual gearbox (although six speeds were homologated for racing), all-wheel drive transmission, independent multi-link suspension front and rear and big disc brakes at each corner.

This road-going version also featured key bodywork revisions needed for racing, with a prominent boot-mounted spoiler, a discreet bonnet lip spoiler just above the grille to improve engine bay cooling and increased intercooler ducting in the front spoiler.

This finely calculated technical equation to suit the 4001-4500cc division also meant the GT-R could whip any challenger for outright race wins too. Which, let’s face it, was the whole point of the exercise!

The ‘Australianised’ GT-R racer

After taking the reins of Nissan Australia’s touring car team in 1985, freshly retired works driver Fred Gibson (who had played a major role in the Group C Bluebird touring car program) got stuck into development of Nissan’s first Group A contender, the turbocharged R30 Skyline which debuted with great success in 1986.

Two years later the new R31 GTS-R came on stream. After a difficult start with numerous technical failures, by 1990 Gibson Motor Sport (GMS) had honed the turbocharged 2.0 litre six-powered GTS-R into a fast, tough and consistent Group A contender that played a decisive role in Nissan claiming its first Australian Touring Car Championship with Jim Richards that year.

So by the time the new R32 GT-R arrived, GMS was highly skilled in the process of finding weak spots in Nissan race cars and eliminating them through local design and manufacture of its own components which only needed FIA homologation approval through head office in Japan.

Given the much greater technical complexity of the R32-based GT-R, GMS again blazed its own development path. With a hefty minimum weight of 1325kg, the all-wheel drive heavyweight proved a difficult beast to tame, but Australian ingenuity and know-how again proved invaluable.

Substantial GMS input led to local production of numerous engine, drivetrain, suspension, brake and ancillary components. A superb six-speed racing gearbox designed and manufactured in Melbourne by Peter Holinger was also specified. Super light and very strong 18 x 11-inch magnesium wheels were designed by Kevin Drage and made in Adelaide by Castalloy.

Nissan’s Electramotive fuel injection and engine management systems developed for US sports car racing were also adapted, along with sophisticated PI data logging software which played a crucial role in the car’s development. GMS and tyre supplier Yokohama also worked together in creating compounds and case constructions tailor-made for the GT-R’s unique requirements.

The GT-R’s braking power was enormous. Up front huge Alcon 14.8-inch diameter ventilated disc rotors were clamped by multi-pot calipers with water cooling. Under the tail were slightly smaller Harrop 13-inch rotors. Even so, brake pad changes at Bathurst were unavoidable.

By mid-1990 Gibson and his men were keen to blood the new GT-R in competition as soon as possible, to weed out any weak links in the complex package before taking it to Bathurst in October.

Mark Skaife was the first driver to race the GT-R when it debuted at round six of the ATCC at Mallala in June, where he held a commanding lead until retiring with a broken front hub. Two works GT-Rs fronted for the penultimate round at Wanneroo; Skaife’s car broke a CV joint getting away from the start line while Richards finished fourth with brake troubles in his first race aboard Godzilla.

For the title decider at Oran Park in July, Richards and his GT-R bolted away from pole position to win the 41-lap race and the championship with what appeared to be ominous ease, after the Japanese supercar had suffered more niggling technical issues in pre-race practice.

At the 1990 Bathurst 1000 in September, the lone GT-R shared by Richards and Skaife showed more glimpses of its future dominance. After GMS had concentrated on refining its race set-up during practice, the GT-R just missed out on a place in the Top 10 qualifying shoot-out.

Come the race, though, Richards quickly spread-eagled the field with the wick turned up, disposing of the 10 fastest cars one by one and taking the lead in the space of only nine laps! Drivetrain problems would soon intervene again, which turned the rest of the race into a high profile test session. Richards won again at the AGP support races before the car retired from the season-ending Nissan 500 at Eastern Creek. However, the best was yet to come.

1991 & 1992: Godzilla’s Path of Destruction

“In touring car racing at least, four-wheel-drive has been so successful that it has almost rendered traditional rear-wheel-drive obsolete,” noted the Australian Motor Racing Yearbook’s review of Nissan’s extraordinary 1991 ATCC result.

“There really isn’t a single track in Australia which doesn’t suit the GT-R. It may be a little awkward through high-speed corners and it may be too technical for most minds to fathom, but with a strong level of staffing and budget that allowed all the necessary homework to be done, the four-wheel-drive Nissans were virtually unstoppable in 1991.

“GT-Rs in the hands of Jim Richards (who won his fourth ATCC) and Mark Skaife destroyed their opposition. Check the statistics: from seven wins out of a possible nine, the GT-Rs finished 1-2 in six of them. Not once did a GT-R driver not stand on the podium during the 1991 Shell Australian Touring Car Championship. Of the 425 laps which made up the nine rounds, 337 of them were led by Nissans. Richards was leader for 229 laps.”

The only car to break Nissan’s stranglehold was Tony Longhurst’s BMW E30 M3, which put in two giant-killing performances at Lakeside and Amaroo Park; circuits that were tailor-made for the brilliant little Beemer.

Otherwise it really was GT-R dominance on a spectacular scale and the trigger for disgruntled Ford Sierra, BMW and VN Holden Commodore opponents to demand governing body CAMS take drastic steps to eliminate such an unfair advantage, either by adding ballast, reducing turbo boost or just banning four-wheel drive altogether.

Having already increased the GT-R’s minimum weight by 35kg for 1991 (from 1325kg to 1360kg), CAMS felt it had done enough penalising of the Japanese juggernaut which continued on its merry way through the remainder of the 1991 season. Rubbing salt into rivals’ wounds was the victory by Mark Gibbs and Rohan Onslow in the Sandown 500, driving a works-prepared GT-R customer car owned by Bob Forbes.

GMS fronted with two works GT-Rs at Bathurst, with the second Drew Price/Gary Waldon car under strict team orders to hang back in the pack a little and be ready for Richards and Skaife to take over in the event of a failure in the lead car. Ironically it was the back-up car that suffered mechanical problems in the race, but as it turned out its assistance wasn’t needed.

After Skaife wound the boost up to set the then-fastest ever touring car lap at Mount Panorama in the Top 10 qualifying shoot-out (2 min 12.63 secs), the lead car enjoyed a faultless and outwardly effortless race, leaving the competition in its wake to cross the finish line a full lap ahead.

Impressive dominance? Yes. Good for the overall health of the sport? No. Everyone agreed that big changes were needed to spice up the show for 1992. Changes to the qualifying and race formats, a new point-scoring system that deliberately did not flatter winners, plus increased lead ballast and engine restrictions for not only the GT-Rs but also their Commodore, BMW and Sierra rivals, were designed to compress the field and stop another runaway winner.

For the start of the season the GT-Rs copped an extra 40kg of ballast (now 1400kg minimum weight) and had a CAMS-approved pop-off valve installed to cap turbo boost levels. Regardless of these handicaps the GT-Rs continued to take most of the spoils, so from round five CAMS increased the Nissan’s minimum weight again - this time by a whopping 100kg - in its increasingly desperate attempts to slow the damn things down!

Even so, at 1500kg and with team boss Gibson claiming the magnesium wheels were starting to crack under the strain, the end result was another Nissan 1-2 finish only this time it was Skaife who defeated Richards to become the youngest Australian Touring Car Champion. And with that victory, Nissan also wrapped its third straight ATCC title.

1992 also delivered the GT-R’s second and last Bathurst 1000 victory in dramatic circumstances. A sudden downpour caught out many drivers on dry weather tyres, including race leader Jim Richards. His slick-shod GT-R aquaplaned and hit the wall on top of the Mountain before crashing out in a multi-car wreck on the exit to Forrest’s Elbow. The race was red-flagged after 143 of the scheduled 161 laps.

In all the mayhem the Johnson/Bowe Ford Sierra had taken the lead before the race was stopped. However, as final results of red-flagged races are based on places held by cars prior to the lap when the red flag is shown, the GT-R was declared the winner - despite crashing out of the race!

The vast majority of rain-soaked spectators (mostly Ford and Holden fans) who descended on the podium presentation clearly didn’t agree with the result. Perhaps some didn’t understand the rules. Perhaps others did but were just tired of Nissan’s two-season dominance and wanted to let them know. Perhaps they were just very drunk.

In any case, the race winners were loudly heckled and booed as they stepped out onto the podium, which prompted a furious Richards to unleash on the mob with a speech that compared them to a part of the human anatomy (a whole pack of them in fact!) which has been immortalised on DVD and Youtube.

That tumultuous Bathurst of 1992 has come to symbolise the end of the GT-R’s brutal reign over Aussie touring car racing. It was always a bitter-sweet relationship with rival teams and race fans, who admired its awesome capabilities and resented its unfair advantage in equal measure. Fact is, the only way CAMS could end Godzilla’s dominance was to change the rules for 1993 to ensure its immediate extinction. Which, let’s face it, was the ultimate compliment.