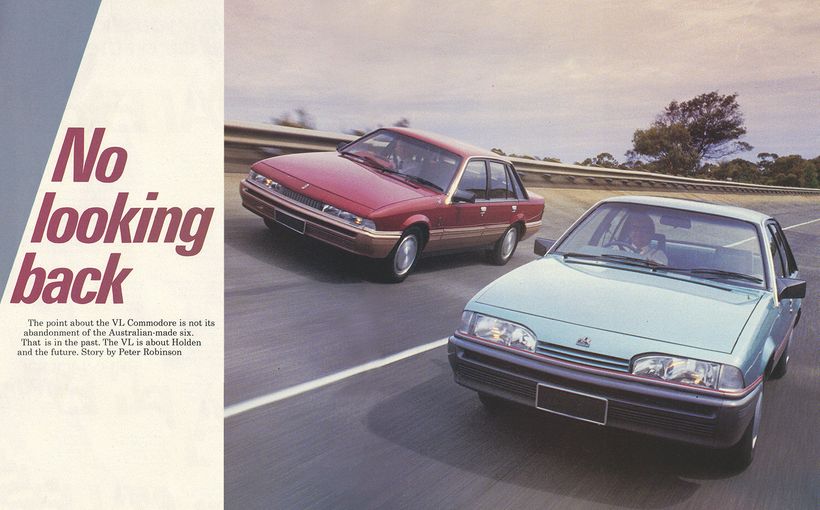

Holden VL Commodore: How Brock and Walkinshaw both won Bathurst

Holden’s VL Commodore holds the unique distinction of winning two Bathurst 1000s during the Group A era. It also won those races in two distinctly different configurations influenced by opposing race teams, during the most turbulent era in Holden’s motor sport history.

The first win came in 1987 for the VL SS Group A - the last Commodore designed and built with input from Peter Brock and his HDT special vehicles operation. The VL’s second Bathurst win came three years later for another iteration called the VL SS Group A SV, developed in partnership with UK-based Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR).

1987 James Hardie 1000: Brock Against All Odds

When Holden and HDT launched the VL Commodore SS Group A in October 1986, it was more a case of evolution than revolution. The previous VK SS Group A with its powerful 4.9 litre (304cid) home-grown V8 had proven to be a fast and tough competitor in the 1986 ATCC and selected rounds of the 1986 European Touring Car Championship. It also won the 1986 Bathurst 1000, thanks to a Les Small-prepared car driven by Allan Grice and Graeme ‘Chickadee’ Bailey.

The new VL SS Group A, of which Holden/HDT had to build a minimum 500 identical road cars to meet FIA homologation rules, featured numerous refinements. The tough A9L-spec V8 had new cylinder head castings to eliminate hot spots and head gasket failures which had haunted the VK, plus tougher valve-train hardware. It was also the last carby-fed Holden V8 and the first to use unleaded petrol.

A new body kit included restyled front and rear spoilers, aero grille and for the first time a functional bonnet scoop to feed cool, dense air directly to the engine’s four-barrel carburettor for maximum power. In Group A race trim, the VL produced more than 400bhp, with a Getrag five-speed competition gearbox, custom-made nine-inch rear axle assembly, fully adjustable suspension and big Harrop brakes.

However, by February 1987 the deteriorating relationship between Brock and his long-time employer GM-H had reached a crisis point. Brock’s resolute belief in the attributes of his Energy Polarizer (based on a new-age science of ‘molecular alignment’ to improve a car’s performance which GM dismissed after its own exhaustive testing) and his stubborn determination to launch a new HDT VL Director model with IRS also not approved by GM-H, were the major catalysts.

On the night of February 20, 1987 Brock publicly unveiled his new Director in direct defiance of GM-H. The General was left with no choice but to serve divorce papers. Peter Brock and Holden, for so long synonymous in the Australian motor industry, had split.

Holden’s decision was enormously damaging for Brock. His race team was no longer Holden’s factory team, all Holden signage had to be removed and his endless free supply of GM parts and technical support was cut off. He wasn’t even allowed to buy parts from

GM-H.

And, without direct supply of new cars to modify, with full GM-H factory warranty/service support, Brock’s HDT road car business was history, too. His loyal deputy John Harvey, who had strived to the bitter end to save the Brock/Holden relationship, promptly resigned along with 1986 team driver Allan Moffat.

In fact, Moffat played a covert role in keeping Brock afloat in the aftermath of the split. By using a middleman acting on his behalf, Moffat managed to purchase the brand new VL Group A Commodore which had just been built by HDT for the 1987 season and launched his own four-race WTCC campaign, with Rothmans sponsorship and John Harvey as his co-driver.

The Moffat/Harvey VL Commodore caused a major sensation by winning the opening round of the 1987 WTCC at Monza in Italy, after the new BMW M3s which filled the top six places were chucked out due to illegal bodywork (lightweight boot lids).

Moffat and Harvey also excelled in round five of the WTCC - the Spa 24-Hour race in Belgium. The Rothmans-backed Holden with the all-Aussie crew was rapidly closing on the third-placed works BMW when it finished an outstanding fourth outright.

Meanwhile, back in Australia the embattled Brock had called on long-time mate Alan Gow to look after his cash-strapped team’s business affairs, as it honoured commitments to major sponsor Mobil by competing in the 1987 Australian Touring Car Championship, Spa 24-Hour and Sandown 500. Although none of these outings produced wins, Brock was focused primarily on getting a good result at Bathurst.

The team fronted with a two-car team at the Mountain, with a new car (No.05) for Brock and David Parsons and a second (No.10) for experienced Bathurst hand Peter McLeod and promising F2 driver John Crooke, who unfortunately would miss out on a drive in the race.

The second car, which had competed at Spa earlier in the year, was there only to fulfil the team’s contractual commitment to Mobil in putting two cars on the grid at Bathurst. As a result, it had literally been bolted together using all the second-hand parts lying around the workshop. Team boss Alan Gow said the team referred to it as “a bucket of bolts.”

This thrifty strategy almost ended in disaster during Friday practice when McLeod narrowly avoided a car-destroying impact with the concrete safety fence, after a steering component failed when approaching Griffin’s Bend at around 200km/h. And to add insult to near-injury, the well-used practice engine and gearbox from the No. 05 Brock/Parsons car was fitted to the No.10 car for the race.

Ironically it was 05 that made an early exit after its engine blew on only lap 34 of 161, so Brock and Parsons made plans to move into the second car. By the time Brock was getting strapped in for his first stint in No.10, McLeod had done a superb job having started from 20th on the grid and during a marathon double-stint dragged it up to a very handy 6th place. Brock, knowing that the car was destined to fail, literally drove it like he stole it so as not to prolong the team’s agony. However, against all odds it just kept going like a train.

Following Brock’s departure, a superb stint by David Parsons saw him set the fastest lap of the three drivers while climbing from 6th to 4th place before a severe rain storm hit. He also managed to avoid crashing while caught out on dry weather tyres before his pit stop, unlike some of the other big names including the man he was chasing for third place, Johnny Cecotto (BMW M3).

The astonishing No.10 Mobil car was in contention for the final place on the podium by the time Brock strapped in for the run to the flag. It was during that last stint, with slick tyres on a slowly drying track, that spectators and an international TV audience were treated to a riveting display of caution-to-the-wind car control.

With his right elbow casually resting on the driver’s door, Brock went from one magnificent high speed power-slide to another for lap after lap with such graceful mastery that all who witnessed it, friend or foe, could not help but be in awe of his skill.

To finish third behind the two Texaco-backed works Ford Sierra RS500s which had dominated the race was the best Brock and his army of supporters could have hoped for – or so they thought. Official protests lodged by Aussie teams over irregularities in the Texaco cars’ front wheel arches were upheld and on November 13, 1987 (about six weeks after the race) the two works Fords were officially excluded from the results and the third-placed Mobil Commodore declared the winner!

It was the slowest winning car on record after starting in 20th place and recording only the 16th fastest lap of the race. It was also the first Bathurst winner to start outside the top 10. And because it was three laps behind the winning Sierras, it completed only 158 of the 161-lap race distance. HDT’s last Group A Commodore was the most unlikely of Brock’s nine Bathurst 500/1000 winners.

1990 Tooheys 1000: Walkinshaw’s Redemption

Following the Brock bust-up in 1987, Holden soon announced it had signed the UK-based Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) as its new racing development partner and joint-supplier of specialised road cars for Group A homologation under a new banner - Holden Special Vehicles (HSV).

TWR was on obvious replacement for HDT as it had already commenced its own assessment of the existing ‘HDT’ VL SS Group A in the UK. Holden and TWR identified two critical areas in which to improve the Aussie car’s performance in Group A racing - engine and aerodynamics.

Holden Engine Company did some major refinements of Holden’s trusty 304cid V8 to increase both power output and durability at high rpm, including a four-bolt main bearing crankshaft, new design cylinder heads with equally-spaced ports and multi-point fuel injection with a new cross-ram inlet manifold fed by twin throttle-bodies.

In regards to aerodynamics, HSV’s motor sport/PR manager John Harvey - who had shared the Rothmans VL with Moffat in 1987 on fast European circuits like Monza and Spa - claimed that at high velocities the car seemed to hit an impenetrable wall of air and was also nervous through high-speed turns. TWR’s own testing produced similar conclusions.

TWR aerodynamicists went to work in the UK’s full-size MIRA wind tunnel to reduce drag and increase downforce. The result was a complex multi-piece kit of composite fibre components comprising huge front and rear spoilers, door and sill side skirts, C-pillar fairings and a large bonnet bulge which incorporated cold air (engine) induction, hot air (radiator) extraction and sufficient clearance for the new fuel injection system.

The aesthetic result of TWR’s long hours in the wind tunnel was widely criticised, but it was clearly function over form and the proof was in the numbers. The base VL’s Cd (aero drag co-efficient) was 0.40, but it was claimed the new SV body kit dropped that to a slippery 0.34 with a tangible increase in high-speed downforce. It was hoped that with these extensive upgrades the Aussie V8 sedan could stem the growing tide of turbocharged rivals from Europe and Japan.

1988

In the meantime local Holden racer Larry Perkins, who had engineered and co-driven three HDT Bathurst wins with Brock in the Group C Commodore era, had been appointed by Holden and TWR to run HSV’s local competition program in 1988.

Much was expected of the new car due to be homologated early in the year, but continual delays in its development and production of the minimum 500 road cars for FIA homologation meant that Perkins had to do the ATCC in the existing ‘HDT’ VL dressed in HSV colours.

The new SS Group A SV didn’t make its belated debut until the Sandown 500 in September. Although clearly outpaced by the Ford Sierras, the turbo cars’ high rate of attrition helped Perkins and co-driver Denny Hulme to claim second place while the second HSV car (Jeff Allam/Armin Hahne) retired with a broken axle.

Three weeks later at Bathurst, Tom Walkinshaw was back in town and Holden’s new Group A contender seemed to be caught in an Ashes-style rivalry between TWR and Perkins. They both fronted with works cars that looked identical, but were in fact from separate workshops on opposite sides of the globe. The Walkinshaw/Allam car had been built in the UK and airfreighted to Australia; the Perkins/Hulme car had been built in Melbourne. And they were run by what appeared to be two separate teams throughout the meeting.

Practice times revealed that Walkinshaw’s new super Holden was on a hiding to nothing against the demonstrably faster turbo Fords. After lodging fruitless pre-event protests against the legality of local Sierras, things went from bad to worse for the burly Scot when the rear suspension of his UK-built Commodore collapsed only five laps into the race.

He later insisted on a stint in the surviving Aussie-built Perkins/Hulme car when it was in contention for a top three placing. After Perkins got back in for the run to the flag, the car retired 24 laps from home with a broken engine rocker and oil pump drive. The fact that suspicions were even raised that the Scot had deliberately buzzed the engine to ensure the Aussies didn’t make the Poms look silly showed how poisonous perceptions of Holden’s ‘intercontinental’ team had become!

1989

In 1989 there were no works Holdens to be seen in the ATCC. Regardless of internal UK/Australia politics, their absence was no surprise given the ever-increasing power outputs and speeds of the Ford Sierras against which the non-turbo V8 Holdens stood no chance in sprint races.

A pair of Holden factory cars only appeared for the Sandown 500 and Bathurst 1000 endurance races (plus the AGP support races as in 1988), but there was no imported TWR car this time. Both were prepared locally by Perkins and presented in a new contrasting black and white livery along with a new name - Holden Racing Team.

Again Perkins, this time co-driven by TWR’s English top gun Win Percy, finished second at Sandown a lap behind a works Nissan Skyline, with the second HRT Commodore of Neil Crompton/Steve Harrington six laps down in 6th place. At Bathurst three weeks later the works Holdens could only pick up crumbs left by the demonstrably superior turbo Sierras and Skylines, finishing three laps behind the winning Ford in 6th (Perkins/Mezera) and 7th (Percy/Crompton) places. It was not a good look.

1990

After two years with Perkins overseeing TWR’s Aussie racing activities, Walkinshaw wanted to take full control of the local operation. In January 1990 he made arrangements for his loyal deputy Win Percy to move from the UK to Melbourne and head up a new Holden Racing Team.

Percy leased an empty factory in outer suburban Ferntree Gully and quickly pulled together a talented and dedicated team under workshop manager/chief engineer Wally Storey and former TWR engine builder Rob Benson.

The new team’s focus from the outset was to win the Bathurst 1000. Its strategy was based on Storey’s plan to develop a car that could be driven flat-out for the full race distance, which would push the highly-stressed turbo cars to breaking point through unrelenting pressure.

A long overdue 85kg weight penalty by governing body CAMS to slow the runaway Sierras was a welcome development, even though the Commodores still had no chance of winning an ATCC round such was the Sierra/Skyline turbo advantage in sprint racing. So HRT instead used the series as an eight-round test session in preparation for Bathurst.

The refinements were extensive. Storey and Castalloy’s Kevin Drage designed a new 17 x II-inch magnesium wheel which was 1.0-inch wider than the previous wheel with improved off-set, brake caliper clearance and cooling.

A superb front brake package was also developed using giant 14.0 inch diameter AP Racing disc rotors clamped by powerful AP six-pot calipers sourced from TWR’s Le Mans-winning Jaguar sports car program. With water cooling and tremendous bite from the latest carbon-metallic pads, this car could out-brake any rival.

Rob Benson also worked hard all year to come up with a Bathurst-winning engine package. After starting the season with about 510bhp, continual development of the fuel-injected V8 resulted in 550bhp at 7200rpm and 450 ft/lbs of torque at 5500-6000rpm, with a power curve tailored to the unique character of Mount Panorama.

The ex-Perkins car which Percy had driven in the ATCC was prepared for Neil Crompton/Brad Jones (No.7) and a new car built-up for Win Percy and co-driver Allan Grice (No.16). Clearly the team did not believe in bad omens, because the new Percy/Grice car was in fact the same UK-built Commodore chassis in which Walkinshaw had suffered that humiliating rear suspension collapse at Bathurst in 1988!

After the new No.16 HRT Commodore showed race-winning pace at the 1990 Sandown 500, both the Grice/Percy car and Perkins Engineering VL shared by Perkins/Mezera qualified ominously in the Bathurst top 10. In the race their faultless reliability and relentless pace saw the Sierras (and the new Nissan GT-R) start to crumble as planned, with everything from rear tyre problems to blown turbos and head gaskets, failed clutches and drivetrains.

As a result the Percy/Grice HRT Commodore powered home to an immensely popular victory and arguably Holden’s greatest Bathurst win. Perkins/Mezera finished third and the second HRT Commodore of Crompton/Jones came home fifth, making it three VL Commodores in the top five.

It had been a long, hard grind over four seasons for the embattled VL Commodore SS Group A, in both HDT and TWR forms, but all the anguish and hard work had certainly been worth it. With two wins in four years, the mighty VL Commodore will always be remembered as one of Holden’s greatest Bathurst race cars.