Ford Model T: from Indy 500 to the Aussie outback

Ford’s legendary Model T - the simple, rugged and affordable car widely credited with putting the world on wheels - was many things to many people. Arguably the greatest contrast was between the US and Australia. In the States it quickly became a favourite amongst street and track racers, while in Australia it became the first mass-produced car to conquer the outback.

“Ts put the masses on wheels and the model became the backbone of early American racing,” wrote Dean Batchelor in The American Hot Rod.

“The first commercially available racing equipment to hop-up a production car was made for the Model T and the cars were used successfully for all types of racing – from Indianapolis to board tracks to dirt tracks to dry lakes and street racing.

“The Model T may well have been created as a car for the masses, but it became a car for the racers.”

This was in stark contrast to the Model T’s life in Australia, where from around 1909 it was shipped here in knocked-down kit form and (until Ford Motor Co of Australia was established at Geelong in 1925) assembled by either state distributors or dealers.

Incredibly, it stayed in production virtually unchanged for 19 years (1908-1927) during which time more than 15 million were produced - and around 250,000 of those were sold in Australia. Its low price, combined with remarkable cross-country ability, appealed not only to everyday motorists but also Australia’s own pioneer of outback automotive adventures, Francis Birtles.

“The Model T was the first car truly suitable for the world’s underdeveloped roads and Australia possessed some of the most underdeveloped road systems in the world,” wrote Warren Brown in his excellent biography Francis Birtles – Australian Adventurer.

“The car ticked all the boxes as the pre-war predecessor to the modern off-road vehicle. (Prior to World War II, few Australians would have heard of four-wheel-drive – with very few exceptions, motor cars came with rear wheels driven only – like the Model T).

“It had fundamental design qualities that catered for poor roads: a wheel at each corner; little or no overhanging bodywork, enabling good angles of approach and departure; low gearing; and high ground clearance. To a large extent the Model T opened up much of Australia, not only through adventuring and expeditions, but because it was a car anyone could drive.”

That’s not to say North America’s vast network of largely rural roads at the turn of the 20th century was much better than Australia’s. Indeed, the Model T’s rough road ability was equally prized by US buyers, particularly the nation’s many farmers, but its role as the catalyst for a booming aftermarket in high-performance parts was not shared here.

Elsewhere, though, the US wasn’t alone in developing speed equipment, which proved the extent of Ford’s far-reaching export program. In Britain for example, there were numerous aftermarket ‘mods’ available for the model with its 177cid side-valve inline four.

And in France, a modified version finished 14th in the first running of the Le Mans 24 Hour race in 1923, equipped with an OHV cylinder head featuring advanced cross-flow intake and exhaust ports designed and manufactured by Montier in Paris. It also drove through a French-made four-speed gearbox.

In 2001 an international jury of 126 automotive journalists from 32 countries voted the Model T the most significant car of the 20th century. It is also arguably the world's most documented car which, given its basic specifications, proves that the simple things in life are often the best.

In early 1900s motoring, the embryonic years of the motor car, simplicity, reliability and ease of maintenance/repair were crucial if this new ‘horseless carriage’ was to gain widespread and rapid acceptance by a largely sceptical public. The Model T ticked all the boxes.

Model T: America’s 100mph budget racer

“This was a time when those who liked cars, but couldn’t afford Packards, Duesenbergs, Lincolns or Cadillacs, had to improvise. And what better could they pick than the Model T Ford,” Batchelor observed.

“Model Ts were plentiful and cheap and most speed equipment that was available was made for the Ford engine. All through the 1920s and well into the 1930s, the Model T engine was a favourite with both track racers and street racers.”

For Aussie enthusiasts, this draws parallels with local motor sport after World War 2, when the creation of ‘Australia’s own car’ in 1948 – the Holden 48-215 – triggered a similar response in the 1950s.

Why? Because just like the Model T, the Holden was also plentiful and cheap, creating a sizeable demand for specialised equipment ‘over the counter’ which could be simply bolted-on to make it go faster.

Batchelor: “The prodigious amount of racing equipment made for the Model T Ford engine included flathead, overhead valve, single overhead camshaft and double overhead camshaft cylinder heads, reground camshafts, special connecting rods, counter-balanced crankshafts (including some five main-bearing conversions), pistons, clutches, carburettors, pressure oiling systems and ignitions – really anything one could want or need to go racing or to create a very rapid street usable car.

“It wasn’t difficult to adapt racing equipment to street use. A little less cam timing, a little lower compression ratio, maybe a single carburettor instead of two, a little heavier flywheel to smoother engine operation and soon you had an engine that produced more than twice the stock horsepower, but was tractable enough for easy driving.”

Numerous aftermarket cylinder heads manufactured for the Model T were no doubt inspired by the brilliant DOHC, four-valve-per-cylinder, four-cylinder race engine created by French manufacturer Peugeot in 1912, which promptly won the Indianapolis 500 the following year.

Print advertisements often referred to ‘Peugeot type’ heads which shows the impact that the French car’s innovative design had at the time, as it established the classic high-performance engine lay-out which is still widely in use today.

“Concurrently with the advent of racing equipment for Ford, Chevrolet and Dodge cars (there was equipment made for other makes but these were The Big Three in those days), a large business developed in building speedster-type bodies to fit these frames,” Batchelor continued.

“These were ultra-simple bodies with few creature comforts or other amenities, but they enabled the impecunious driver to emulate the factory-built speedsters. And, with the lighter weight of these special bodies and a bit better aerodynamics, a Ford Speedster with a hopped-up engine was a pretty fast car; many of them were able to top 100mph which, in the 1920s and ’30s was a tremendous feat.”

Francis Birtles and the Model T in Australia

We usually consider 'motor sport' to be men and machines competing against each other on a race track. However, in Australia at the dawn of the 20th century, it was more a case of man and machine battling for survival against a formidable opponent - the outback.

“It should be remembered that when the Model T arrived people knew little about cars in Australia at the time,” wrote Margaret Simpson in her insightful article Henry Ford’s Model T and its impact in Australia for the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.

“It wasn’t unusual for them to spend one or two days trying to start the new imported car without realising that the tank needed petrol. Others would spend years driving in one gear not knowing how to, or realising that you could, change gear.

“There were few formed roads, no garages and petrol supplies. Petrol was scarce and expensive and was purchased in tins from a few chemists and grocers. Cars were often unreliable and there were no mechanics, so drivers had to repair breakdowns.”

It was around this time that the man who was destined to become Australia’s most famous (some would say infamous) early automotive adventurer, Francis ‘Frank’ Birtles, had already made quite a name for himself on wheels.

Although his most famous and celebrated conquest – becoming the first man to drive a car (Bean) from England to Australia – in 1927 was a long way in the future, by the time of the Model T’s Australian arrival Birtles had already achieved some superhuman feats on pushbike.

In 1905 he was the first cyclist to complete a west-east crossing of Australia and by 1912 he had pedalled around Australia two times and crossed it seven times, including in 1911 setting a new cycling record between Fremantle and Sydney of only 31 days. During this time he documented his achievements in books and magazine articles, illustrated with his own photos.

Having achieved so much under pedal power, Birtles was naturally intrigued by this new contraption called the automobile. In 1912 he used his navigational skills to assist Syd Ferguson in a single-cylinder Brush runabout to be among the first Aussies to make a west-east crossing of the continent by car.

In September that same year Birtles, accompanied by his brother Clive (an excellent motor mechanic and driver) and Frank’s hardy bulldog Wowser, left Melbourne in a 20hp Flanders on a vast drive north up the east coast then west to the Gulf of Carpentaria, before arriving back in Melbourne in January 1913.

Birtles learned everything he needed to know about cars on that trip; how to service them, replace or repair things that broke, get them stuck and unstuck and, most importantly, how to improvise a repair when the required tools or parts were not available – in other words, the art of ‘bush mechanics.’

As a vehicle for long-distance travel Birtles knew the car had no equal - and public intrigue made it a magnet for publicity. The Gulf trip also opened Frank’s eyes to a new world of commercial opportunity, as he realised that most people didn’t travel outside of major cities and towns but were intrigued by what lay beyond them, as Warren Brown explained.

“Now, with the combination of the phenomenal distance-busting motor car and a (motion picture) cinecamera, Frank could do all this for them. He could bring Australia – the real Australia – to Australians. He was now finding his niche as Australia’s intrepid outback adventurer.

“What he needed was an automotive partner – a bit of quid pro quo whereby a car manufacturer could use Francis Birtles the intrepid adventurer and he could use their cars. Frank was now becoming a household name and he was quick to capitalise on it.

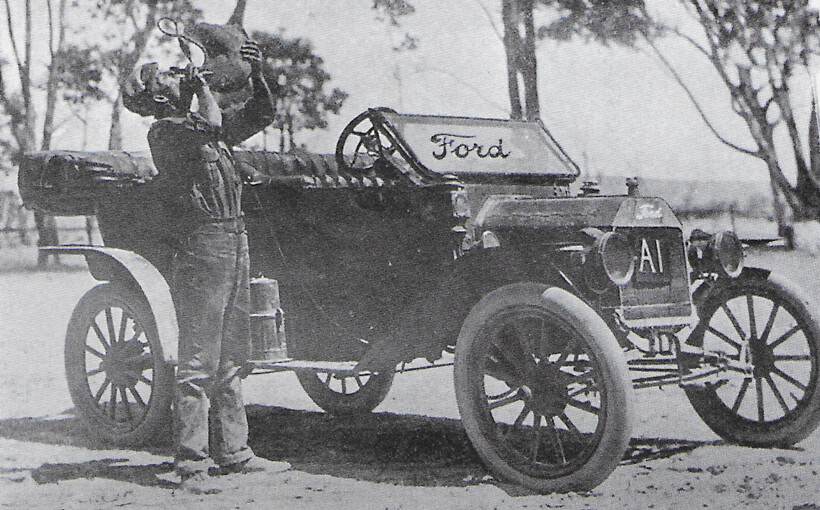

“He found an excellent patron in Ford Motors which kicked off an extremely successful publicity campaign using Frank as their adventuresome spokesman. It seemed a marriage made in heaven – the ubiquitous and robust Model T, the first car truly suited to Australian conditions, put to the test by the only bloke who really knew the outback, Francis Birtles. If anyone was going to prove a Ford’s reliability, it’d be him – why, his life depended on a Ford.”

According to Brown’s detailed account, in August 1913 the NSW Ford distributor shipped a brand-new Model T from Sydney to Far North Queensland where Birtles took delivery at Charters Towers, about 130km inland from Townsville.

From there he commenced a three-week 5,600km solo drive north-west to Burketown in the Gulf country before heading south through outback Queensland and NSW to Sydney and onto Victoria’s Port Phillip Bay.

In 1913 this was an epic drive by any measure and a publicity bonanza for Ford, with Birtles making personal appearances at dealerships along the way. Ford also produced some neat promotional books title Across Australia in a Ford by Francis Birtles, presented in a personal diary-style format with lots of photos he took along the route.

For many potential buyers, these books not only proved the unbreakable ruggedness of the Model T in convincing them to become owners, but also opened their eyes to a world of adventure in their own backyard.

Although the number of Ford expeditions Birtles made was never accurately recorded, his role as the brand’s most high-profile ambassador continued until around 1920. His numerous magazine articles always featured photos of Model Ts in places you would never expect to see a motor car.

Other significant outback trips by Birtles in Model Ts included a 5,000km journey resulting in the widely acclaimed feature film documentary Into Australia’s Unknown, masterfully shot by the young and ambitious cinematographer Frank Hurley.

And in 1915, in the same unbreakable Model T which Birtles and Hurley had driven the previous year, he left Sydney for a seven-month journey to retrace the tragic Burke and Wills expedition of 1860-61 from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Frank’s documentary of this epic journey, titled Across Australia in the tracks of Burke and Wills, attempted to find answers to the many questions Australians had about the ill-fated trek in which all but one man - John King - perished. The film’s cinema release late in 1916 earned rave reviews and even more kudos for the mighty Model T.

However, retracing the tracks of Burke and Wills more than half a century later was not without its own potentially lethal challenges, which Birtles was quick to point out according to Brown.

“It will be remembered,’ (Birtles) said ‘that King, in his evidence before the Inquiry Commission, stated that the horses and camels of the expedition knocked up (died) in the sun-cracked level country which is subjected to the overflow of the Georgina River. It is terrible country. I nearly perished through running out of water. For 36 hours I battled without a drop of water and just managed to reach the river.”

Towards the end of his time as Ford’s outback ambassador, Birtles and another of his much-loved canine companions ‘Dinkum’ headed for Cape York in search of gold. However, in remote south-west Queensland, chillingly not far from where Burke and Wills perished at Cooper Creek, Frank and his trusty Model T struck trouble.

Whipped by fierce sandstorms, Birtles was making slow progress across steep sand dunes as swirling sand and grass clogged the Model T’s radiator. Inevitably the overheating engine could take no more and blew a head gasket. His repair job, contaminated by insects and flying grit, lasted only a short while before the damaged gasket blew again. Now in serious trouble, Birtles drew on all of his self-taught bush mechanic skills to survive.

Brown: “With no spare gasket, Frank set about cutting a makeshift one out of the Model T’s canvas folding roof. He figured it might just seal if he smeared it with enough axle grease. He tightened the head back on. Bang! It blew before the car reached 100 yards.

“Dinkum raced around the back of the Model T, snapping at the wheels to get it to move. Frank hadn’t given up either. With his pocketknife he began to cut a head gasket from his leather suitcase, strapped to the back of the Ford. It too failed. By now, all the close-fitting machined surfaces on the head and block were filthy and the leather gasket just couldn’t seat properly.”

With the masterful use of some brass shims, Frank managed to resuscitate what was left of the original head gasket and get underway again, but it too continued to fail. So he had another go at making a replacement gasket, this time by cutting up an old fibrolite carry case. He soaked the gasket in hot oil before smearing the gasket, head and block facings with the only sealant he could find - apple jam!

With careful driving, he somehow managed to keep his crippled Model T heading north for a staggering 3,000km, before another head gasket failure allowed the No.1 cylinder to fill with water and shatter the piston.

Fortunately, Frank had a spare on board, but now with the onset of the wet season - which would make any vehicle travel impossible - he sought the help of a local Aboriginal tribe in dragging his dead Model T to higher ground. For the next few months he lived in a cave on a mountainside high above the flood plains.

Brown: “Frank stayed with the tribe for some time until eventually the floodwaters subsided. One day, two Aborigines from an outback station arrived with mail – spare parts including two new head gaskets. Frank made his way back to the car, now sitting in grass three metres high. The magneto was shorted, battery flat and everything rusted. It took him two weeks to get the car going, all the while living on ‘sand palm tops and black bream.’

“My gold-mining venture did not prove successful and after a short while I headed back across the continent, travelling on three cylinders,” Birtles wrote. “There was no compression in number one, water and grit having cut out the white metal connecting-rod bearings. It took me six months to travel two thousand miles, then one day, while going down a steep grade in desert country, the gasket blew again.

“Water jammed on the compression stroke and a big piece blew out of the wall of number three cylinder. In a howling sandstorm, I walked to the railway. I camped there and after a few weeks of waiting, managed to get hold of an old Model T Ford engine. I bolted this to the chassis and threw the other engine away. This carried me back to Melbourne.”

By then Francis Birtles’ days as a Ford-backed adventurer were coming to an end, but his many outback expeditions with the US marque ensured the utmost admiration and respect for the legendary Model T in Australia.