Western Australia’s own ‘wild colonial boy’ Ross Dunkerton wrote the Datsun 240/260Z’s winning chapter in Aussie motor sport history virtually single-handed, due to his unparalleled success in local rallying. His top-shelf navigators included John Large and Jeff Beaumont. Here ‘Dunko’ and Beaumont are captured in full flight during the 1977 Warana Rally in Queensland. Image: Chevron Publishing

It’s a paradox that one of the most beautifully proportioned and elegantly styled sports cars - the iconic Datsun Z car – achieved its greatest motor sport success in the brutally tough world of rallying. The 240Z was twice winner of the notorious East African Safari and together with its larger capacity 260Z successor won back-to-back Australian Rally Championships in the 1970s.

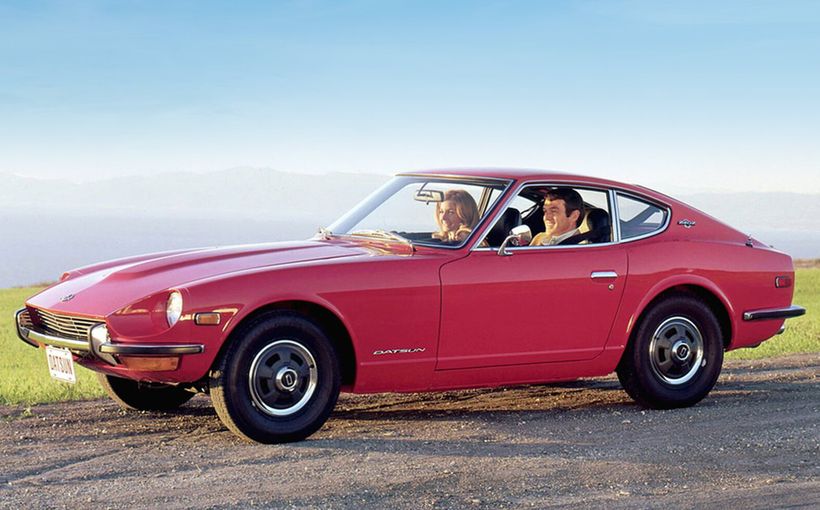

When launched in 1969, the 240Z set new benchmarks not only for contemporary sports car styling but also affordable and practical ownership. By contrast, its long bonnet, short tail, inline six cylinder engine and overtly rearward driving position seemed inspired by classic British sports cars of the 1960s, like the Austin Healey 3000 and E-type Jaguar.

However, if such British sports car icons did provide some of the new Z car’s design inspiration, the Japanese brought new world standards in manufacturing tolerances and refinement combined with Nissan’s rugged twin-carb SOHC 2.4 litre inline six, supple long travel independent suspension and a very strong unitary body-chassis unit with a relatively light 1043 kg tare weight.

It was these factors which combined to make the 240Z a winning rally car, which could well have been one of its design targets from the start. After all, Nissan’s primary competition focus at the time was on conquering high profile rally events to demonstrate the ruggedness and reliability of its products on the world stage.

The Datsun 240Z joined the ranks of African rally legends after winning the world-famous East African Safari in 1971 and 1973. Here the 1971-winning works car crewed by Edgar Herrmann and Hans Schuller powers through sharp rocks and choking dust on its way to an historic victory for Nissan. Image: www.blog.beforward.jp

The Z cars proved to be very effective in notoriously harsh environments like Australia and East Africa, but less so in Europe. Although its well-designed independent rear suspension provided excellent traction, the weight of a cast iron-blocked straight six hanging over the front axle line made it prone to understeer.

That and the Z’s long frontal overhang also resulted in a relatively high polar moment of inertia, which made it less responsive to rapid-fire directional changes than rivals like the tiny Renault Alpine A110 that was proving dominant in Europe. The 240Z was larger and heavier and a bit of a beast by comparison, requiring a rather brutish driving style to extract the most from it.

The launch of the 260Z in 1974 included the option of a new 2+2 body style on a 300mm longer wheelbase to appeal to a wider buyer demographic. However, in competition terms, the most significant change was in the engine with a longer stroke (from 73.7mm to 79mm) raising its capacity from 2393cc to 2565cc. This resulted in small increases in power (from 151 to 162bhp) and torque (146 to 152 ft/lbs) but the rally cars remained on the original 90.7 inch (2304mm) wheelbase.

Ross Dunkerton and John Large in their 260Z pushing hard in Victoria’s Akademos Rally during the 1975 ARC. Note how the wild-haired Dunkerton chose not to wear a helmet; such safety devices were not compulsory in local rallying in those days! Image: Chevron Publishing

The Australian Way: Dunkerton’s ARC three-peat

WA rally star Ross ‘Dunko’ Dunkerton was unquestionably the most successful Z car competitor in Australia, winning the Australian Rally Championship in 1975 and 1976 in a 260Z and 240Z respectively, plus claiming a third consecutive title in 1977 in which his 240/260Z 'hybrid' also played a decisive role.

Although Nissan had ended its East African Safari program by that stage (see separate story), the fast and determined West Australian proved that there was still plenty of winning left in the company’s stylish two-seater in local forests.

1975 ARC

WA state rally champion Dunkerton and his ace navigator John Large contested most of the ARC rounds in 1974 and finished third overall. Boosted by their competitiveness against the country’s top rally crews, they decided to have a serious crack at winning the 1975 championship in a privately-entered 260Z with limited sponsorship from Channel Nine Perth and Ansett Airlines.

And that’s exactly what they did, winning two of the seven rounds and finishing equal first in another with a Z crewed by South Australia’s Stewart McLeod and Adrian Mortimer. The SA team also finished second overall, in a title fight that saw Datsuns win all but one round.

The bright camera flash shows the intense concentration on Dunkerton’s face as he and navigator John Large guide the rorty 260Z to second place in the 1975 Mazda House Rally in northern NSW. This was the opening round of the 1975 ARC, which got the WA crew off to a strong start. Image: Chevron Publishing

There was plenty of quality on show in the 1975 ARC, with most of Australia’s top rally crews appearing at different events throughout the season. However, none of them could match the dogged consistency of Dunkerton and Large in a car that was largely stock with minimal preparation - it didn't even have a roll cage!

Reigning champions Colin Bond and George Shepheard had to forfeit their much-loved Torana XU-1 to blood the Holden Dealer Team’s new LH Torana L34, which didn’t appear until the third round. After winning Bega’s round four, a gearbox failure in the next event ended the reigning champs’ title hopes in their new V8-powered Holden.

Other outstanding Datsun performers included southern NSW farmer George Fury in a works-prepared 710, who won the opening round and was holding a commanding lead in the Bega until forced out with suspension failure in the closing stages.

Fury’s pain was Dave Morrow’s gain as he powered to victory in a highly modified 2.4 litre 180B SSS. Rising Canberra star Greg Carr added to Datsun’s dominance by winning the final round in another 180B SSS. The only non-Datsun victory went to South Australia’s Dean Rainsford and Graham West in an exotic Porsche 911 Carrera RS.

Dunkerton’s tenacious victory was as much a tribute to his driving skills as it was to his fierce determination and sheer physical endurance. Between his business commitments, Dunkerton had to prepare the car himself for each event and then tow it across The Nullabor and back when he competed on the east coast – a 10,000km return trip each time.

The fact that he also managed to win the WA championship again that year, in between his ARC commitments, is a testament to his tenacity.

Dunkerton (with arms crossed) waits while his 1976 ARC-winning LHD 240Z works car gets some attention at a service stop during Queensland’s Warana Rally. Note the unusual international registration plate and bank of four powerful driving lights which turned night into day on the many special stages held after dark.

1976 ARC

John Large was adamant that he and Dunkerton had done more than enough to become part of the factory-backed Datsun Rally Team in 1976 under the new management of former Ford competitions boss Howard Marsden.

However, when Datsun offered to provide a fully maintained LHD ‘works’ car but would not cover the WA crew's expenses, Large promptly quit in disgust and was replaced by Jeff Beaumont. Dunkerton's new mount was one of the 240Zs which had been prepared by the factory in Japan for the East African Safari but was never used.

Eventually Datsun changed its mind and the 240Z crew did enjoy some factory support. This proved to be the right call - in terms of results, at least - as Dunkerton and Beaumont drove superbly to win four of the six rounds and convincingly seal a second title for Datsun. They were also the only crew to compete in all the rounds, so consistency was again a crucial factor in their success.

The 1976 ARC got off to a bad start. The first round, which was twice postponed due to torrential rain, had to be cancelled. Some of the remaining rounds were also disrupted by either poor event organisation (competing crews actually went on strike in WA!) or infuriating wrangles over vehicle eligibility with governing body CAMS.

The crew worst hit by these disputes was George Fury and Monty Suffern in their works-entered Datsun 710. They won several rounds but scored no points because their car didn’t comply with the highly restrictive ARC rules, even though it was eligible for the Southern Cross or any other major FIA-sanctioned international rally! The rapid 180B SSS crewed by Greg Carr/Wayne Gregson suffered the same fate, prompting their sudden withdrawal.

Dunkerton in the LHD ‘works’ 240Z muscles the big six cylinder coupe through a tight turn on his way to third place in the 1976 Castrol International Rally in Canberra. With Jeff Beaumont reading the maps this pair was the class of the ARC field that year, only to be dumped by the Datsun Rally Team at season’s end due largely to personality clashes.

So the main rivals for Dunkerton/Beaumont were again Rainsford/West in their potent Porsche Carrera RS. The South Australian crew won WA’s opener and led the championship for several rounds until two retirements in succession dashed their title hopes. Strong competition also came from the very quick David Jones/Ian Pearson Galant which finished third overall ahead of Danny Bignall’s Datsun 240Z.

Ed Mulligan’s thundering V8 Torana L34 contested three rounds but was plagued by axle failures and Evan Green/John Bryson finished runners-up in round five driving an exotic ‘works’ Alfetta GT direct from Europe.

Then, in the first of two bizarre twists, Dunkerton was unceremoniously dumped from the works team at the end of the season as his brash personality and wild partying ways were not compatible with Marsden’s and Datsun’s more disciplined approach.

Although the Z cars didn’t star on Australian race tracks, it was a different story in the US where John Morton won the SCCA’s C-Production National Championship in 1970 and 1971. His immaculate 240Z was prepared and run by West Coast-based Brock Racing Enterprises (BRE) which under team founder Pete Brock (no relation to ours) set the standard for US production sports car racing. Nice job concealing the headlight pods which caused some aero drag at high speeds. Image: www.wired.com

1977 ARC

CAMS wisely dropped its suffocating vehicle eligibility rules for the ARC. The decision instantly breathed new life into the championship, as many top teams entered the series.

These included Fury/Suffern in their now ‘legal’ works 710, Mitsubishi rally ace Doug Stewart in a works Lancer GSR, Dave Morrow/George Shepheard in HDT’s new Gemini and Datsun ace turned Ford works driver Greg Carr in a new Mk 2 Escort RS2000. As a result the 1977 ARC was a thriller, with a different winner at each of the five rounds and the title not decided until the final event.

Having rolled his LHD works 240Z late in the season, Dunkerton regrouped for 1977 as a private entrant driving a hybrid - his 1975 ARC-winning 260Z fitted with all the running gear salvaged from the damaged 1976 car.

Dunkerton’s bid for a hat-trick of titles got off to a flying start with a strong second place in the opener and a home ground victory in WA’s round two. By that stage he had a substantial early points lead, but a rare engine failure in round three sidelined the Z and left him looking for an alternative drive to defend his crown.

The Datsun 240Z and 260Z proved popular choices for Aussie production sports car racers in the 1970s, as they were relatively affordable to buy with low maintenance costs due to excellent reliability. Two examples that competed on local tracks during the early 1970s were driven by Michael Conner (left) seen here at Philip Island in 1974 and ‘L. Brennan’ at Calder in 1972.

This triggered the second bizarre twist in this tale. Marsden, having sacked ‘Dunko’ the previous year, figured it was better to have the recalcitrant West Aussie driving for Datsun rather than against it. So he hastily arranged for Dunkerton/Beaumont to step into one of the works team’s 710s for the final two rounds! This sporting gesture gave them enough points to finish in equal first place with ‘team-mates’ George Fury and Monty Suffern in the other works 710.

So, two Datsun drivers were declared joint winners of the 1977 ARC, which Dunkerton could not have achieved without the strong performances of his 240/260Z in the early rounds. 1977 was also the end of the Z car era in top level Aussie rallying as smaller, lighter and faster cars like Datsun Stanza and Escort RS became the new pace-setters.

Nissan works driver Rauno Aaltonen played a decisive role in developing the 240Z into a winning rally car. Here the flying Finn is doing just that in the 1973 East African Safari, although he would later slide wide on a muddy turn and roll over an embankment. Image: www.pinterest.com

Conquering the Safari

The East African Safari was always ‘the big one’ as far as Nissan was concerned and the international event it most wanted to win. The fact that its works-entered Datsun 240Zs won it twice, first on debut in 1971 and again in 1973, proved works driver Rauno Aaltonen’s claim that it was the ultimate car for the Safari at the time.

Based in Kenya with loops into neighbouring Uganda and Tanzania, the Safari was hellishly tough. Its car-munching distance of 5,000 km included everything that the wilds of Africa could throw at competitors, from roaming wildlife to rock-throwing locals, baking hot sun and blinding dust to torrential rains, flash floods and thick mud. For the Japanese, a Safari win was a badge of honour.

The company took its first tentative steps in East Africa in the early 1960s with its Bluebird and Cedric sedans. Although success initially proved elusive, Nissan’s engineers learned quickly and by 1970 had developed the twin-carb ‘SSS’ version of its popular 510 sedan (aka Datsun 1600) into the company’s first outright Safari winner.

Naturally, Nissan was hungry for more African victories but also recognised that it needed a bigger, tougher and faster car in response to increasing competition from top European factory teams. The new 240Z was the ideal replacement.

Cutaway of a factory-prepped 240Z destined for Monte Carlo duties shows the detailed preparation that went into these cars. Even so, by today’s standards they appear remarkably stock. Note triple twin-choke side-draught carbs, single roll-over hoop and spare tyres/tools neatly secured under the rear hatch. Image: www.tech-racingcars.wikidot.com

Preparations for 1971 involved a two-pronged attack, because in addition to its African strategy, Nissan’s primary European target was the Monte Carlo Rally. The new 240Z works cars were built in two specifications. One batch was in high-riding Safari trim while the other was tailored for the Monte Carlo’s smoother and faster roads with lower suspension and more power.

Africa or Europe, these works rally machines never strayed far from their production line origins, as proving the strength and durability of the showroom product was of paramount importance to the Japanese.

The torquey 2.4 litre SOHC inline sixes, armed with three twin-choke side-draught Mikuni-Solex carburettors, were claimed to produce 200bhp. Close-ratio five-speed gearboxes and limited-slip diffs got power to the ground through 14 x 6-inch magnesium alloy wheels.

There was also massive underbody protection and to minimise weight all removable body panels were exchanged for fiberglass replacements and clear polycarbonate side/rear windows replaced the original glass items. The crews sat in lightweight fiberglass rally seats, with tools and two spare wheels/tyres mounted in the back.

Nissan is so proud of its rallying heritage that it has not only kept many of its winning cars but also preserved them in the condition in which they finished their careers, warts and all. Above are the 1971 (No.11) and 1973 (No.1) Safari winners. Each of these 240Zs survived 5,000km of merciless high-speed punishment across one of the harshest places on earth. Their hard-earned wins were richly deserved. Image: www.nissan-global.com

The Safari Zs had slightly less power (lower compression) to safeguard against inconsistent fuel supplies, but they were still capable of top speeds of 130 mph (200 km/h plus) over some of the worst terrain imaginable. The African cars also had extra driving lights mounted high on the bonnet in streamlined pods and at the base of the windscreen pillars.

The 240Z made its Monte debut in 1971 and the best result from Nissan’s three-year works campaign was a third place for Aaltonen in 1972. The 240Z also made its East African debut in 1971 and the reigning champions came well prepared with three cars for Rauno Aaltonen/Pieter Easter, Uganda’s Shekhar Mehta/Mike Doughty and Kenyan-based German ace Edgar Herrmann/Hans Schuller who won the 1970 Safari for Nissan in the 510.

Aaltonen set a lightning pace in the early stages only to suffer suspension and driveshaft problems which forced him to ease off to make the finish. A humiliating collision between the rival works Porsche 911s left local Safari specialists Herrmann and Mehta to fight for the win in their 240Zs – and with no team orders! At the finish Herrmann had beaten Mehta by only three minutes in accumulated times. It was a thrilling contest and a dream Safari debut for the Z cars.

The works 240Zs also made guest appearances in major Australian rallies. Here Rauno Aaltonen and navigator Steve Halloran are snapped setting a blistering pace in the 1972 Southern Cross International, on their way to a close second place behind Andrew Cowan’s works Mitsubishi Galant. The 1972 event was a thriller, with the winner only decided in the final stages.

The 240Zs struggled in 1972 with a variety of mechanical gremlins, but Mehta got it all together in 1973. He and co-driver ‘Lofty’ Drews claimed victory on countback in their battered 240Z, after finishing in a dead heat with a works-entered Datsun 180B SSS. It was the closest finish in the event’s history.

With two Safari victories in three years, Nissan had nothing left to prove about its mighty 240Z. 1973 was the last appearance of the works cars, even though private and semi-works Zs did continue to compete in Africa and elsewhere.

And that included Australia of course, where the 240Z and 260Z will always be remembered as two of Nissan’s most accomplished Australian rally performers. And arguably the most beautiful.