Austin X6: unique Aussie rally winner with a Marathon pedigree

When Irish ace Paddy Hopkirk finished runner-up in the 1968 London to Sydney Marathon driving an Austin 1800, it proved how well suited the front-wheel drive British sedan was to the rigours of long-distance rallying. However, the short showroom life of its unique Australian replacement, the six-cylinder Austin X6 (better known as the Kimberley and Tasman), ensured it could not build on the 1800’s legacy despite winning a round of the Australian Rally Championship.

That breakthrough victory occurred in 1972 when Adelaide-based John Taylor and navigator Graham West beat a top-quality ARC field, which included the HDT’s all-conquering LJ Torana GTR XU-1s, to win round five of Australia’s premier rally competition.

The winning X6 was a private entry, which gave a glimpse of the car’s rallying potential had it remained in production. Sadly, the smartly-packaged X6 range launched in 1970, available in Tasman and more upmarket Kimberley model grades, never met its lofty sales targets (poor quality control and misguided marketing didn’t help) and ceased production in 1972.

Even so, it’s interesting to ponder what a superb long-distance rally car British Leyland Motor Corporation Australia (BLMCA) had on its hands, given that it was based on the Austin 1800 which - if not for some cruel twists of fate - could easily have won the London to Sydney Marathon.

Sure, the 1800 with its 1.8 litre four-cylinder engine and relatively heavy 1150 kg kerb weight was not considered a potential competition car when launched in 1965, particularly given the phenomenal success of its smaller, lighter and faster Mini Cooper S siblings.

However, long distance rallying requires a different mind-set to short-stage forest rallies. To succeed in this discipline, the emphasis is not only on tank-tough construction but also low-stressed mechanicals, supple long travel suspension and good load carrying capacity.

And in that context, it soon became clear to BMC management (before its merger with British Leyland in 1968) that in the Austin 1800 they had an ideal contender for the more rugged long-distance events that the smaller Minis were not well suited to.

The Austin 1800’s compact four-cylinder engine it shared with the MGB was (like the Mini) mounted laterally, with its four-speed manual gearbox and front-wheel drive transmission mounted beneath it. That meant there were no vulnerable tail-shafts or rear axle assemblies exposed to the rough stuff and the compact engine/gearbox unit could also be well protected from damage.

The space-efficient mounting of the engine also meant that 70 per cent of the 1800’s generous 106-inch wheelbase was available for luggage and passengers with ample leg room. Given the three-man crews and hefty equipment carried in the Marathon cars, this was also a major plus.

The four-door bodyshell was also very rigid and widely regarded as the strongest ever made by the company’s Longbridge UK plant. It was also blessed with short overhangs front and rear which kept most of the laden weight within the wheelbase for consistent ride and handling.

In addition to sharp rack-and-pinion steering and power-boosted front disc brakes, arguably the 1800’s greatest attribute in this application was its ability to literally ‘float on fluid’ as the corporate advertising claimed.

Its ‘Hydrolastic’ semi-active independent suspension, which connected actuators on all four wheels to a common hydraulic fluid circuit, responded to different road surfaces and driving styles with consummate ease.

All of these strong points added up to a vehicle which, in competition, possessed a rare ability to travel quickly over rough roads and across vast distances, with enviable comfort and durability.

The X6 range therefore inherited most of these attributes, plus with its new six-cylinder engine theoretically addressed the four-cylinder 1800’s only major shortcoming identified during the Marathon - a need for more power.

Austin X6: Tasman and Kimberley

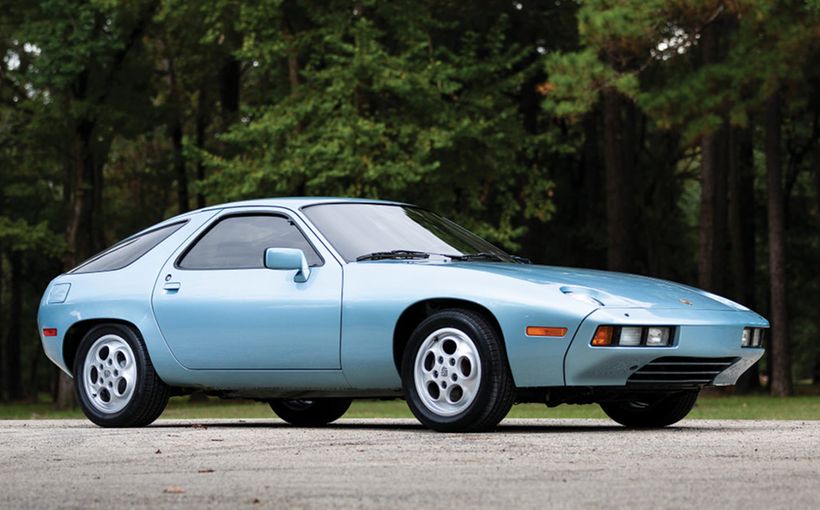

The X6 replaced the 1800 in the Australian marketplace in November 1970. Although the new Tasman and Kimberley twins were in effect “thoroughly logical updates” of the 1800, Gavin Farmer in his definitive book on the Leyland P76 points out that the unique-to-Australia X6 range broke new ground on a global basis.

“What is not generally recognised is the fact that the X6 twins from BLMCA were the first volume production saloons - in the world - to be powered by a transversely-mounted six-cylinder engine driving the front wheels." In other words, another great Leyland concept that was way ahead of its time - think Toyota Camry V6.

Farmer also points out that British Leyland’s design centre manager Roy Haynes was in charge of the relatively inexpensive - yet very successful - restyle of the 1800, which was a joint effort between David Bentley and chief designer Harris Mann. For reasons unknown to Australian management, though, this handsome design was not adopted for UK production.

“Only six exterior body panels were changed – three at the front (guards and bonnet) and three at the rear (guards and boot-lid) but the appearance was transformed.” Another clever yet inexpensive styling tweak was replacement of the 1800’s rearmost side-glass with a solid panel, resulting in a thick C-pillar effect which enhanced the X6’s visual solidity.

The base-model Tasman and more upmarket Kimberley were well defined, with the latter’s plusher interior including front bucket seats, four rectangular headlights and greater body ornamentation contrasting with the Tasman’s more basic trim (including bench seats which could carry six adults) and simpler grille with single round headlights.

Power for both came from the same transverse 2.2 litre six-cylinder SOHC adaptation of the 1.5 litre E-series four, which would later be increased to 2.6 litres for use in Leyland’s P76 and Marina Six. The Tasman version of the X6, equipped with a single SU carb, was rated at 102bhp @ 5500rpm. The Kimberley, initially offered with twin SUs, had 115bhp.

The front-wheel drive transmission offered a choice of four-speed manual or Borg Warner three-speed auto. The 1800’s superb Hydrolastic suspension was recalibrated to suit and it would be safe to say that no other Aussie-made car at the time could come close to the X6 twins in terms of ride quality. Attributes, you would have to say, of an effective rally car.

Austin X6: an ARC winner

We know of more than one X6 that competed in Australian rallying, but the most successful on a national basis was the South Australian-based car backed by Adelaide’s Taylors of Medindie dealership and crewed by John Taylor and navigator Graham West.

Although event reports always referred to their X6 as a Kimberley (and it could well have started life that way) it looked like a Tasman with its single round headlights and simpler grille.

Either way, according to a Racing Car News report at the time, it served as a company demonstrator and test mule before being assigned to rallying duties. That was in 1971, when BLMCA was gearing up for a factory-backed attack on Australia’s most prestigious rally, the Southern Cross International.

The Kimberley was initially prepared for Southern Cross duties by Roadsafe at Taren Point in Sydney for Taylor and West, who were joined by Evan Green/Peter Brown (Mini Clubman GT) and Andrew Cowan/John Bryson (Mini Cooper S) in a three-car team resplendent in the company’s pin-sharp blue and white corporate colours.

Although showing glimpses of competitive pace in their new and untested car, Taylor and West were dogged by suspension troubles and other setbacks during the event. John Bryson in his RCN event report (while also navigating for Cowan in the works Cooper S) took note of the X6’s potential:

“The last 18 miles were in terrible dust. The car in front was rather rapid and I was surprised to find it was Taylor’s Kimberley. This car will be competitive, as he was hard to stay with even though the shock absorbers had given up. He should have fitted Armstrongs. This fault was to lead to more front-end problems that stopped a good run.”

After the Southern Cross, the Kimberley was returned to Roadsafe where it was stripped down in expectation of another rebuild for the next event. However, before that could happen BLMCA followed its cash-strapped UK parent in abandoning direct involvement in motor sport, leaving the stripped-down X6 gathering dust.

However, John Taylor (like Bryson) had sensed potential in the new X6 during its troubled Southern Cross outing and made arrangements with the factory to acquire the car “in a million pieces” according to its new owner.

In early 1972 Taylor and mechanic Duncan Campbell rebuilt the Kimberley into a reliable car for the coming season. Prior to taking possession, Taylor and West had been rallying an ex-Marathon 1800 and experience gained with that car proved invaluable. The philosophy was to select the components which had worked best in the 1800 and transplant them into the X6.

Terry Douglas at Roadsafe had been in charge of the six-cylinder engine’s development when first built for the 1971 ‘Cross and it required few changes. With input from specialist race engineering firms including Lynx and Waggott, the right balance of camshaft and carburation (comprising triple 1.75-inch SUs) resulted in a reliable 145bhp – at least 30 more than the standard Kimberley engine – and increased torque.

Importantly it also offered great flexibility at low revs, with a strong torque surge from 2000rpm. It was also safe spinning to 7000rpm in the top cog of the four-speed gearbox with a terminal speed in excess of 100mph (160km/h).

The Hydrolastic suspension remained close to stock, apart from uprated Monroe Wylie GT 130 shocks and replacement of adjustable (and therefore troublesome) lateral tie-bars between the lower inner suspension pivots with standard non-adjustable bars. Wheels were lightweight Globe Rallymaster alloys with Dunlop tyres.

Lighting was increased with a special wiring loom designed by Taylor to support two Cibie headlamps in place of the standard units, plus four additional Cibie/Lucas driving lights mounted on the bumper bar. A large reversing light was also Cibie.

Most of the stock interior was retained, but front seats were replaced with special rally recliners from the 1800 and the dash layout revised to give Taylor and West best access to their relevant instruments and switches. The rear of the cabin was reserved for tools and spares, including a hydraulic hand-pump with gauge indicator to reset the suspension height after a hard day’s rally driving.

Two spare wheels/tyres were carried securely in the boot along with sand mats, winch and cables. The 1800’s long range 25-gallon fuel tank also found a new home in the X6’s boot, connected to twin SU electric pumps to feed the engine’s triple SUs via a CAV fuel filter.

It was a very solid, robust and capable car that would have been formidable if it had been around to compete in the London to Sydney Marathon. However, like the 1800, the only major negative was its power-to-weight ratio, which wasn’t in the same league as the dominant rally car of its era – Holden’s six-cylinder LJ Torana GTR XU-1. It also couldn’t match the Holden’s superior rear-wheel drive traction, particularly in hilly terrain.

As a result, it generally couldn’t match the stage times of the fastest Toranas in either ARC or SA state championship events, which tended to be only a few hundred km in distance. For the X6 to have a sniff of victory at ARC level, it would need an event which allowed it to play to its strengths.

The Equaliser: 1972 ARC Rd 5

“Locals Dominate Rothmans!” screamed the headline for RCN’s coverage of the Rothmans Walkerville 500, South Australia’s round five of the 1972 Australian Rally Championship.

To describe the result as an ‘upset’ would be an understatement, because not one of the top eastern state crews – including the Holden Dealer Team - finished in a major placing. And the first six were taken by Adelaide-based crews!

As a point-scoring ARC round, the Walkerville 500 attracted a powerhouse entry featuring numerous factory-backed cars. Reigning champs Colin Bond/George Shepheard were joined by Frank Kilfoyle/Mike Osborne in a pair of HDT XU-1s. There was also Ford backing for two rapid Escort Twin Cams for Peter Robertson/Roger Bonhomme and Bruce Hodgson/Fred Gocentas.

And Chrysler Australia, in its home state, also mounted a three-car Galant attack, with Doug Stewart, Doug Chivas and Bob Riley as drivers.

The (320-mile) 500km event started at 4.30pm on Saturday October 28, with the 46 assembled cars and crews departing Wayville Showgrounds Theatrette towards the Adelaide Hills before heading north-west to the start of three divisions of competitive stages about 100km from the state’s capital.

The first division saw damage and/or demise for some top contenders, including Doug Chivas in his works Galant which ended up on its roof after he misjudged a T-junction. Local star Stewart McLeod’s XU-1 suffered a loose rear wheel causing considerable damage, championship leader Bond suffered two punctures, team-mate Kilfoyle re-arranged his Torana’s door and Robertson damaged his Escort Twin Cam’s front suspension.

Doug Stewart clean-sheeted division one in his works Galant to take the early lead, but he had seven crews all with single-point penalties breathing down his neck, led by Hodgson’s Escort in second and the Taylor/West Kimberley in third.

Navigation errors in the second division took a heavy toll on the front runners, with Stewart (Galant), Riley (Galant), Hodgson (Escort) and Kilfoyle (Torana) all copping heavy penalties for missing control points. However, as many of the top ARC crews struggled to find the correct route, Taylor/West exploited their local knowledge and navigation skills to remain high on the leader board.

The best performer in the second division was the local Pennell/Lock XU-1, which dropped only one point to lead the field into the third and final division ahead of the Taylor/West Kimberley. The Stewart/Bryson works Galant withdrew with a blown clutch before the start of the third division, which claimed more interstate victims.

Hodgson, Kilfoyle, Bond, Watson (Renault) and McPherson each missed another control point to slip further down the order. The Pennell/Lock XU-1 was maintaining its tenuous lead over the Taylor/West Kimberley until a missed control point put an end to their spirited challenge.

What levelled the playing field for the South Australian teams was not only having strong knowledge of local roads. There was also a high degree of traditional map-reading navigation required. This was common at club and state level, but increasingly rare in the ARC with its growing emphasis on vehicle performance and driving ability with a minimum of navigation. The 1972 Competition Yearbook concluded that:

“The arguments could rage forever over whether it was or wasn’t easy navigation, or whether it favoured local crews who had some prior knowledge of the area, but the fact is that many recognised top crews became lost for lengthy periods on many sections and local South Australian crews took the first six outright placings.”

And at the head of that list was the Taylor/West Austin Kimberley, recording the X6’s first and only ARC victory. The Adelaide-prepared car displayed consistently high speeds on local roads its SA crew knew well, combined with faultless reliability.

This against-the-odds win also spoiled what would otherwise have been a clean-sweep for the all-conquering HDT XU-1s, which won every other round of the 1972 ARC. Such a giant-slaying victory would also have been advertising gold for Leyland, had the X6 range not gone out of production at around the same time it scored such a significant triumph.

We can only wonder how different the Kimberley/Tasman story could have been if these unique Australian six-cylinder cars had been given the chance to exploit their strengths in long distance rally events, just like the Marathon-bred Austin 1800 on which they were based.