MGA and MGB: Aussie doctor and the world's fastest ‘Super Bee’

The MGA and MGB were the ultimate in MG sports cars during the halcyon days of Australian production sports car racing (ProdSports) in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, at one stage it was claimed that a locally-developed MGB was the fastest Prodsports MGB in the world.

That bold statement, by none other than parent company British Leyland, was in 1971 when Queensland doctor Iain Corness and his hand-built ‘Super Bee’ were part of the company’s factory-backed racing team called the British Leyland Young Lions.

In reality, Leyland’s claim would have been difficult to authenticate, given that Australia was little more than an international backwater at the time and MGBs were competing successfully in other much larger markets including the UK and USA.

Even so, by 1971 the Super Bee was more highly developed than even factory-backed MGBs competing in the UK, given that it was equipped with a unique locally developed DOHC engine.

And after several seasons it was continuing to set new lap records, with one remaining unbeaten for eight years. On some tracks it was recording similar times to the top V8 Mustang touring cars of its day.

So, to understand how Australia ended up with one of (if not the) fastest MGBs in the world, we need to take a brief step back in time to recap MG’s post-war activities and put the MGB’s achievements into context.

MGA

As Britain slowly emerged from the rubble of World War 2 in the late 1940s, its primary focus was on increasing exports and earning foreign capital to rebuild its shattered economy. Any manufacturers sharing this vision were given favourable support by the UK government, so car manufacturers responded with development of new models with global appeal.

Naturally this included the much-admired MG sports car marque, which in 1955 launched the striking MGA at the Frankfurt Motor Show. Its slipstreamed fully enclosed bodywork was a major departure from previous T-series MGs, having been developed initially for Le Mans where three MGA prototypes competed in the 1955 24 Hour classic only months before the production version was launched in September.

Under that seductive skin was a robust and conventional (but compared to the dazzling Citroen DS launched the same year, outdated) body-on-frame design, powered by BMC’s 1.5 litre B Series inline four with twin SU carbs and a four-speed manual gearbox. Suspension was coil-spring independent up front with a leaf-spring live rear axle. Steering was rack and pinion and brakes were four-wheel drums with a choice of solid steel or wire-spoke wheels.

Most MGAs were destined for overseas buyers, particularly in the lucrative US market where the MG badge had been made popular in the early post-war years by GIs returning from Europe with much-loved examples of their little T-series sports cars. The MGA was also well received and many soon found their way into competition use.

The company responded with the faster but flawed MGA Twin Cam in 1958, featuring a DOHC aluminium cylinder head on a larger capacity 1600cc B Series block, plus four-wheel disc brakes. However, the Twin Cam was short-lived largely due to its compression ratio being too high to avoid detonation with most pump fuels. Warranty claims climbed, sales plummeted and the Twin Cam was promptly axed in 1960.

Even so, the pushrod 1600cc MGA sold in healthy numbers until 1962 when it was replaced by the MGB. Although most were sent to the USA, some were shipped to Australia as CKD kits and assembled by Pressed Metal Corporation at Enfield in Sydney.

As a result, the MGA in its various forms was raced extensively in both countries and with considerable success. In North America it was very popular from its 1955 arrival, winning numerous regional and national championships hosted by the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA).

In Australia it was equally popular in production sports car racing in the 1950s and 60s, being affordable for clubman racers to purchase and maintain. There were no national championships for ‘proddies’ in those days, but they did enjoy considerable success in circuit racing, hill-climbs and rallies.

And MGAs were raced by some of the biggest names in the game in the early years of their careers, including future Ford works driver and Bathurst winner Fred Gibson and retail tyre magnate Bob Jane.

MGB

Released in 1962, the MGB featured clean and well-proportioned styling with universal appeal, combined with the latest in rigid yet lightweight unitary or ‘monocoque’ construction which consigned MG’s traditional body-on-frame design to history.

Even so, the drivetrain and suspension were largely revisions of the MGA hardware with a larger 1798cc version of the twin-carb B Series four, which was upgraded from a three-bearing to a stronger five-bearing crankshaft in 1964.

Like the MGA, many MGBs ended up Stateside, while smaller volumes found their way to Australia. They were initially assembled from CKD kits by Pressed Metal in Sydney before production moved across town to British Leyland Australia’s Zetland manufacturing plant in 1968. However, MGB production ceased only four years later, due to unfavourable tariff laws designed to increase local content.

Even so, the MGB found many loving owners during the near-decade it was available in Australia and many found their way into competition, primarily in production sports car racing which peaked in the 1960s. And it was in this environment that rivals would feel the ‘sting’ of a potent competitor.

Birth of the Super Bee

In a fascinating article published in the out-of-print and sadly missed Australian magazine, The BMC Experience, the Super Bee’s creator and driver Dr Iain Corness penned a personal tribute to his famous car which provided many first-hand insights.

Iain Corness and his wife Carole (who also competed in the Bathurst 500) raced an MGA in local ProdSports racing for a couple of years before they travelled to the UK in 1967 where Iain completed his medical degree

Corness payed close attention to the UK racing scene, where he met works-backed MGB driver Bill Nicholson. An invitation to inspect the MG factory at Abingdon soon followed, where Corness was shown all the ‘hot’ parts needed to upgrade the MGB’s standard 1.8 litre B Series to full-house race tune or 'Stage 6' in competition department lingo.

He returned to Australia armed with engine hardware he’d need to build a car purely for competition use, including a Stage 6 steel crankshaft, oversize forged pistons and high-lift camshaft with competition valvetrain to match.

He found a nice 1965 MGB roadster, but after deciding it was perhaps too nice to race he put it up on blocks to serve as a parts donor for his actual race car, which started as a bare shell from the wreckers that had been stolen, stripped and torched. The fire was actually the first step in stripping weight out of the car, as it had melted away all the sound-deadening compounds and even the lead-based wiping metal between the panel joins.

In a cramped, dirt-floored workspace under his Brisbane home, Corness and pharmacy student John Campbell built the MGB racer in six weeks, working till midnight every weeknight and all-day on Saturdays with Sundays being their only day of rest. By modern standards it was pretty simple stuff, but for a pair of amateur racers relying on 'how to' books as their only form of guidance, it was a sizeable challenge.

The five-bearing engine was removed from the road car and rebuilt to Stage 6 specs. The road car’s front crossmember and suspension were transferred with uprated coil springs, re-valved shocks and revision of the lower front suspension geometry to eliminate bump steer. The road car’s live rear axle was also employed, with the two bottom leaves mounted on top of the spring packs (to lower the ride height) and anti-tramp rods fitted.

The burned-out shell came without door hinges, so Corness and Campbell improvised with what were, in effect, “reverse gull-wing” doors hinged from their lower edges instead. This also saved weight, as the original hinges were very heavy. To trim more fat, the bonnet and boot lid were re-made in fiberglass, using moulds taken from the road car. They also made a set of fiberglass wheel arch flares modelled on Mini Cooper S flares, to shroud the wider racing tyres and steel-spoke wheels with single ‘knock off’ nuts. The windscreen was more a wind deflector, made from a single piece of Perspex.

Corness made his own grille and instrument panel out of aluminium. However, more specialised fabrication like the roll bar and racing fuel tank were outsourced. The car’s Wildfire Green paint was applied by a spray painter neighbour, who was tired of all the noise each night and figured the sooner the car was finished, the sooner he would get some sleep!

1969: a dream debut

They confidently called it the ‘Super Bee’ and even displayed a bumble bee decal on the boot lid. The hand-built MG was a bit rough around the edges, but its lighter body and powerful Stage 6 engine resulted in an excellent power to weight ratio which ensured it was fast from the outset.

The Super Bee made its debut at the first meeting for 1969 at Brisbane’s Lakeside Raceway and immediately impressed, with both Iain and Carole recording times in the 69-second zone which Corness claimed were faster than any MGB on the challenging Queensland track.

During the 1969 season, the Super Bee continued to lower its times, getting down to consistent 65s at Lakeside while also setting new benchmarks at Katoomba’s Catalina Park and Sydney’s Oran Park. By the end of the year it was Australia’s quickest MGB “by a country mile” which attracted plenty of attention, including a track test by Racing Car News with glowing reviews. The British roadster was also inching closer to the top of the Prodsports category and there was more to come.

1970: British might in blue and white

Proof of the car’s rapid ascendency in its debut season was an approach by British Leyland Australia for Corness to join its official works team - the Young Lions - in 1970. However, like all factory teams, BLA demanded a high standard of presentation.

So the Super Bee was given a make-over at the company’s Brisbane workshop by body and paint specialist Derek Allison. This included the correct hanging of doors, bonnet and boot-lid and getting the sheetmetal blemish-free (Iain also made a new set of aluminium wheel arch flares) before the garish green disappeared under Leyland’s corporate blue and white colours. It looked so sharp, the car was renamed ‘Super Bee II’ to erase all memory of the rough-and-ready original.

Refinements continued throughout 1970. Stripping as much weight out of the car as possible remained a primary focus, achieved in the best traditions of creative rule interpretation.

This included gutting the doors but leaving small pieces of Perspex protruding at the tops and securing the winder handles with brackets. To the outside world it looked like there were full window glass and winder mechanisms inside, but permanently fixed in the open ‘race’ position.

Hole saws of different diameters were used to remove surplus sheet-metal in many places that could not be seen and the heavy standard door hinges were drilled out, along with numerous bolts. A new lightweight racing seat was fabricated and the suspension continued to be refined.

No surprise that the Super Bee II’s lap times, with both Iain and Carole driving, continued to tumble on their favourite Queensland and NSW circuits, with Lakeside dropping to 63s and Oran Park to 51s, with Warwick Farm around 1min 45 secs.

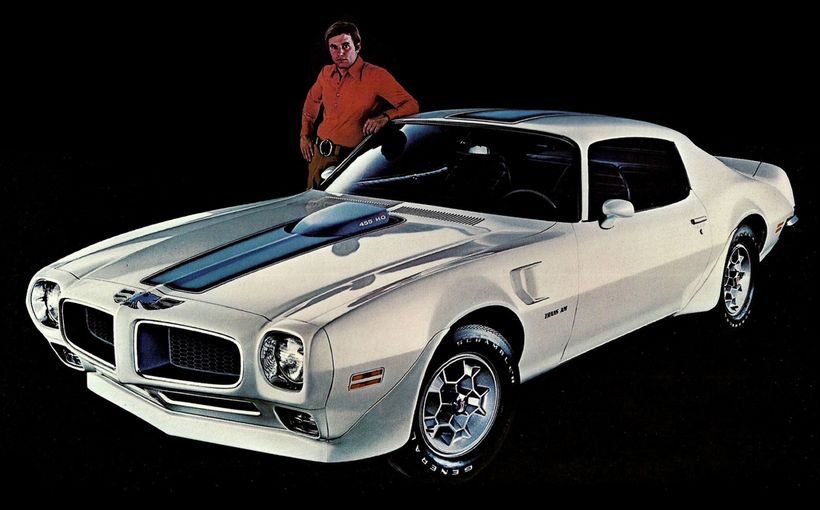

While there was still no MGB that could come close to matching the sting in the tail of the Super Bee, Corness could still not match the race-winning pace of British Leyland team-mate Ross Bond’s highly developed Austin Healey 3000. Corness simply needed more power, but with the B Series engine at the peak of its development, the solution would require some lateral thinking.

1971: fast but fragile

Fitting an MGA Twin Cam head to the Super Bee’s steel-cranked B-Series block was the brainchild of engineer Col Vaughan. Such a change was permitted under the Prodsports rules at the time as there were no restrictions on cylinder head design. Indeed, the inline six in Ross Bond’s benchmark ‘big’ Healey was fitted with a trick 12-port crossflow head, so it was literally a case of ‘if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em’ for Super Bee II.

Talented engine tuner Ivan Tighe was given the job, but it was a challenge from the outset given that the aluminium DOHC head was a 10-stud design trying to fit on an 11-stud block. It also created a sky-high 15:1 compression ratio, which required the combustion chambers to be enlarged. However, that in turn ruptured the water jackets, with the solution requiring lots of skilful aluminium welding and machining.

The MGB’s oil galleries also did not align with the Twin Cam’s, which required more improvisation by Tighe. He also devised a clever crankshaft drive for the twin overhead camshafts which were given Repco-Brabham grinds, along with a new set of pistons manufactured to his design by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) in Port Melbourne.

A set of four-into-one exhaust headers and an inlet manifold for two 45mm side-draught Weber carbs, both hand-made by Brian Payne, were the finishing touches on what Corness proudly claimed was the world’s first MGB Twin Cam with an eight-port crossflow head.

Although no dyno figures were quoted, it would be safe to assume this definitive version of ‘the world’s fastest MGB’ engine was up around 200bhp. Along with some minor cosmetic updates, the car’s name was also updated to ‘Super Bee III’. 1971 was another memorable year but not always for the right reasons, as Corness explained:

“The extra power systematically broke everything from the flywheel bolts backwards. It dropped valves; it broke pistons; it threw rods; but even though it was unreliable, it set lap records and won races.

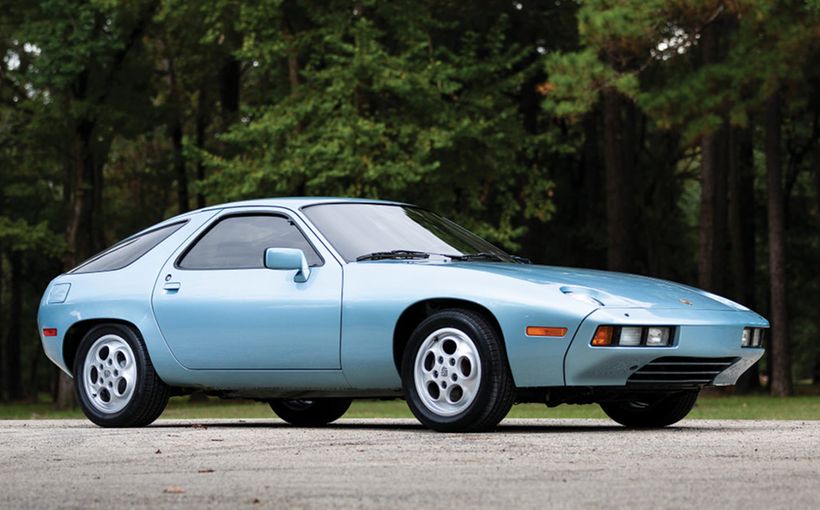

“But it was a very physical car to drive, requiring more strength than Carole could muster, so in 1971 I was the solo driver. The Lakeside time of 61 seconds remained unbeaten for eight years and Super Bee only lost that when they opened the class from under 2.0 litres to under 3.0 litres and Alan Hamilton’s Porsche took the record away.”

1972: end of the road

Through sheer persistence Tighe did get on top of the powerful engine’s reliability woes by the end of the season. And there were plans for a genuine ‘factory lightweight’ Super Bee IV for 1972, with Leyland UK promising to stamp a full aluminium body using the MGB production dies.

However, with the model being discontinued in Australia that year, the aluminium body did not eventuate and the Leyland Young Lions racing team was disbanded. Any plans Corness may have had to continue racing on his own were also shelved, after CAMS placed new restrictions on ProdSports modifications which effectively outlawed the country’s top cars.

Corness parked the MGB and went motocross racing instead. He sold it two years later without the special Twin Cam engine. It was raced in pushrod form without success, before disappearing from the tracks and into hibernation for more than three decades.

It was not until 2008 that the car was dusted off and purchased by Queensland enthusiast Ian Rogers, who undertook an authentic restoration to its 1970 Young Lion’s ‘Super Bee II’ specification. It now competes regularly in Historic racing; a fitting revival for an Australian sports car racing icon which will always be remembered as the world’s fastest MGB.

*Special thanks to The BMC Experience publisher/editor Craig Watson for his valuable assistance with this story.