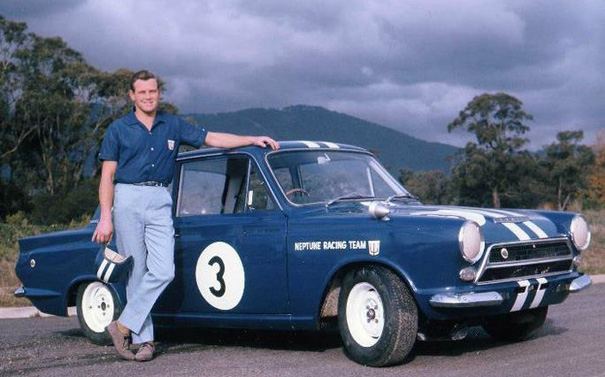

Made In Australia: Jim McKeown and the world's fastest Lotus-Cortina

Back in the 1960s, Allan Moffat claimed that Neptune Racing Team driver Jim McKeown had the world’s fastest Lotus-Cortina.

That was a quite an accolade, given that Australia was a motor racing backwater at a time when the lightweight Lotus-tweaked Cortina was Ford’s front-line weapon in small-bore sedan racing and rallying across the globe.

However, Moffat was well qualified to make such a judgement as he really had his finger on the pulse of Lotus-Cortina performance, not only in Australia but the UK and USA.

Moffat was creating a name for himself locally in an ex-works Lotus-Cortina he’d bought from Team Lotus at the end of the 1964 US racing season and shipped back to Australia.

Fitted with a full-house works engine prepared by BRM in the UK, Moffat was able to directly compare the performance of his ex-factory car against not only McKeown’s all-conquering Neptune machine but those raced by Bob Jane and the Geoghegan brothers.

Today, McKeown vividly remembers that his confrontations with Moffat in those days were intense and often brutal encounters.

“He came out and had a real lunge at me trying to grab my Shell Neptune money,” Jim told Shannons Club. “He put everything into it and tried really, really hard but he never quite made it.

“We had some pretty hectic races I can tell you. I particularly remember the fight we had for the 1966 South Australian Touring Car Championship at Mallala (single race format). There wasn’t much left of either of our cars when we’d finished!”

At the time Moffat was also attracting attention in the US racing Lotus-Cortinas, after scoring his first and only outright victory in a round of the SCCA’s now legendary Trans-Am series at Bryar, New Hampshire in 1966.

On that historic day, driving a privately-entered car with a BRM engine and trick Goodyear tyres, Moffat knocked off everybody including the big dollar Lotus-Cortinas fronted by Alan Mann Racing which had replaced Team Lotus as Ford UK’s factory team in the US.

Moffat knew he could raise the bar even higher with McKeown’s obvious power advantage, so he did a deal to borrow Jim’s engine for a tilt at 2.0 litre class honours in the 1967 Trans-Am series opener at Daytona. McKeown joined him in a second car with a works BRM engine.

Despite claiming pole position and leading the early laps, a loose flywheel that came adrift ruined Moffat’s big chance to prove how Jim’s home-grown Aussie ingenuity could conquer the world’s best.

Regardless of the Daytona debacle, the record books show that McKeown’s Lotus-Cortina was a stand-out performer, with a staggering race-winning ratio of around 90 percent in Australia that raised eyebrows around the world.

The Victorian ace won numerous state Touring Car Championship titles and smashed 1.6 litre class lap records at every track he raced on during a memorable era of motor sport.

When McKeown met King Neptune

Jim McKeown started motor racing in the late 1950s in a variety of sports cars before developing a taste for racing sedan cars.

After sharing a class win with George Reynolds in the 1962 Armstrong 500 and third place in the 1963 event, Jim stepped up to the latest Ford Cortina GT and then his famous Lotus-Cortina. It wasn’t an ex-factory race car like Moffat’s but still had its own claim to fame.

The low mileage showroom-spec example was of one of the first Lotus-Cortinas produced by Ford, instantly recognisable by the separate oval-shaped front indicator lights.

It was first registered for road use in 1963 bearing Victorian rego plates HUN 999 after having been imported by Peter Coffey of Coffey Ford dealership fame.

In early 1964 McKeown was invited to join a new three-car racing team that had been put together by Norm Beechey.

With backing from Neptune, a subsidiary brand of oil giant Shell, the newly formed Neptune Racing Team had maximum spectator appeal by representing the three most popular makes at the time – Holden, Ford and BMC.

As a result, Beechey was armed with a piping hot version of Holden’s EH S4, McKeown in his remarkably rapid Lotus-Cortina and Peter Manton in his giant-killing Mini Cooper S.

Beechey had learned plenty during his time with David McKay’s Scuderia Veloce multi-car race team, setting a standard of presentation with his new squad that was a benchmark for the era with all three Neptune Racing Team cars presented in identical dark blue with white racing stripes.

How McKeown built a world beater

At the time, Jim McKeown was also running a busy automotive repair shop and tow truck business in Kilsyth at the foot of the Dandenong Ranges in Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs.

“In those days Kilsyth was still mostly unsealed roads and apple orchards, so we were what you might call hillbilly mechanics,” McKeown said jokingly.

“We used to know the local police pretty well. The senior sergeant would often ring up and say ‘I know where you tested your car at midnight last night because I had all the locals on the phone, so calm it down a bit!’ They were different times for sure. When I first got the Cortina it was stock standard and we gradually developed it over a period of time. She was basically a home-grown special.

“We discovered pretty early on that the Poms were very conservative in their valve lift and valve timing. The factory type of (race) engines they sold were pretty tame compared to ours. We were running very high-lift cams with longer durations and much greater valve overlaps.

“It was a bit of a job putting high-lift cams and bigger valves in when there wasn’t enough room for the valve springs and what have you. It took a lot of fiddling around to make it all fit. We basically hot-rodded it and squeezed every little bit out of it with the valve sizes and cams we were running.”

Fact is, McKeown’s locally developed version of the Ford-based 1558cc engine with its two-valve DOHC aluminium cylinder head went a lot further than just camshaft and valve development. The whole engine was stretched to its limits in every dimension.

These days, the list of skilled hands and minds that worked on the car reads like a who’s who of Australia’s top race engineers.

In addition to Jim himself, the hot-rodding skills of Jack Goldsmith Godbehear, George Wade (Wade Cams), Eddy Thomas (Speco-Thomas) and Peter Holinger (Holinger Engineering) all had significant input in the Neptune Cortina’s development, which gives you some idea why the car was so fast.

Engine highlights included a Laystall steel billet crankshaft, Cosworth rods and wedge-top pistons; a stout bottom end capable of withstanding the spine-tingling 8500 rpm rev limit required to get the most out of the engine’s big-breathing top end.

The heavily baffled sump was also extended downwards, greatly increasing the engine’s oil capacity to combat oil surge and improve its air cooling. A thicker core radiator kept the lid on engine temps.

The standard 40mm DCOE Weber chokes were enlarged to 45mm, feeding 130-octane aviation fuel into reworked combustion chambers with a sky-high 13.5:1 compression ratio. Jim admits suffering some blown head gaskets running such big compression, but said it was worth it for the obvious power gains.

The end result was a mini monster motor. Lotus quoted 105bhp at 5500rpm for the Lotus-Cortina engine in stock form. The best figure Moffat saw from a BRM works engine was 170 bhp. Jim’s engine was pumping out 15-20 bhp more. No wonder Moffat wanted it!

“The main thing was that at the time our work on the car coincided with Jack Brabham running the (Tasman and F1) Repco-Brabham engines and George (Wade) used to supply all of the camshafts for the guys at Repco Research (in Melbourne).

“George made a number of special camshafts for me, which we experimented with until we found the best one. He also did the valve springs for me. He had a test rig that he used to run the various lobes up on to check valve spring harmonics and all the rest of it.

“It had a lot of top-end power but we did suffer a bit down low. The engine wouldn’t really start to pull until 4500-5000rpm, so you had to have the gearing right to keep it revving (and not lose air speed through the ports).

“Peter Holinger made the gearboxes for me, so we had three or four different ‘boxes with different ratios to suit different circuits. He used to do all of that work in his little tin shed out the back of Warrandyte (another outer eastern suburb near Kilsyth).

“We had lots of different diff ratios too, right down to 4.9:1, so by mixing and matching the gearboxes and diff ratios we could come up with a combination that got the best out of the engine at any track.”

Jim had considerable freedom with engine development but the same could not be said for the car’s unique rear suspension, in which Lotus replaced the Cortina’s standard leaf springs with coil-over shocks, a pair of trailing arms and an A-frame to positively locate the live rear axle.

The A-frame design consisted of two pivoting trailing arms angled at 45 degrees that joined at a single mounting point beneath the diff housing.

Jim said it might have been good in theory but in competition use it placed too much strain on the banjo housing, causing the alloy diff housing bolts to work loose and leak oil.

“That A-frame was a horrible thing, but under the rules I had to stick with it for the whole time I raced the car,” he lamented.

“I don’t think Colin Chapman (Lotus) gave it too much thought to be honest. I think it was more a gimmick and part of his sales pitch to Ford. When we first got the car we were getting beaten by Harry Firth and Pete Geoghegan in their Cortina GTs (with leaf spring rear-ends) because they just out-handled us.

“The geometry was all wrong because with the A-frame bolted to a bracket below the diff it made the rear roll centre too low. That’s why they used to lift the inside wheel all the time through the corners.

“We overcame that to a certain extent by reinforcing the diff (casing) and we changed the pickup points on the axle housing so that the trailing arms were on top rather than underneath. Then we basically stiffened it all up with much higher spring rates all round.

“No one knew much about springs and shocks in those days, but I had a contact at Central Springs in the city and they made us a lot of different coil springs that we played around with. We also had adjustable Armstrong shocks.”

Colin Chapman was renowned for his obsession with minimising weight in cars of his design and the Lotus ‘Type 28’ (Lotus-Cortina) was no exception.

Early models like McKeown’s came standard with lightweight aluminium doors, bonnets and boot lids, plus alloy bell-housings, gearbox casings and differential housings. Claimed kerb weight was less than 900 kgs.

Even so, Jim trimmed even more weight out of his by using lightweight aluminium aircraft nuts and bolts to replace steel equivalents throughout the car.

Widened steel wheels ran either Dunlop ‘green spot’ or softer ‘yellow spot’ racing tyres. The 9.5-inch Girling front disc brakes and 9.0-inch rear drums ran sintered metal pads and linings. The front discs were also fed lots of cooling air through aluminium air scoops mounted beneath the front beaver panel.

“There was no big secret or mystery about that car,” Jim concluded. “It was the result of a joint effort by a group of people that had a lot of good ideas and we just played around with different bits and pieces to come up with the best result. I was very proud of what we achieved.”