The 1974 World Cup Rally was a 17,000 km-plus torture test from London to Munich via Africa. At one stage a Leyland P76 was leading. And had it not become lost in the Sahara desert, due to flawed route instructions that plunged the event into chaos, the all-Australian sedan could well have won the toughest and most demanding of all the global Marathons.

The fact that it was also one of only a handful of finishers was as much a testament to the skills and gritty determination of its driver Evan Green and navigator John Bryson as it was to the numerous design and engineering attributes of the much maligned P76 that made it such a formidable world class Marathon car.

Indeed, it was the P76’s unique engineering principle of a light engine in a light but strong car that made it the ideal Aussie sedan for such an enormous challenge. The 1974 World Cup Rally was the P76’s most memorable achievement in motor sport.

1974 World Cup Rally

Following the success of the first event from London to Mexico in 1970, it was agreed that a World Cup Rally would be held every four years, always start in London and always finish in the city hosting the World Cup soccer tournament that year.

In 1974, the host city was Munich in Germany. However, as the direct road distance between London and Munich was only about 1,000 kms, some major detours would be required to create the vast distance and difficulty demanded for such a world class event.

The lure of Africa and the world’s greatest desert, the Sahara, prove irresistible to organisers. The 1974 World Cup Rally would travel south from the UK through France and Spain before venturing further south into Africa and the treacherous Sahara. It would then pass through Sicily and southern Italy, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Austria and Germany to the finish in Munich. A marathon distance of 17, 209 km to be completed in just 21 days.

It was something of a miracle that the 1974 World Cup Rally even took place, given the growing political instability in Africa and the Arab-Israeli war in October 1973 which triggered petrol shortages and the world’s first energy crisis.

In the nervous oil-starved months following the conflict, numerous factory teams had decided (incorrectly as it turned out) that it would not be politically prudent to take part in an event seen to be selfishly burning up what was now seen as a precious resource.

It must be said that the absence of many factory teams played perfectly into the hands of intrepid Aussie motoring journalist/rally driver Evan Green and his seasoned navigator John Bryson, as it became evident that a well organised private entry with a little luck on its side had a good shot at winning.

Green had represented British Leyland’s works team as a driver in the two previous Marathons, which included an Austin 1800 in the 1968 London-Sydney Marathon and a troublesome Triumph 2.5 PI in the 1970 World Cup Rally. However, Leyland had since withdrawn from competition leaving Green and Bryson with the task of finding sponsors and purchasing and preparing a suitable car back home in Australia.

The Big Car Challenge

Green and Bryson gave considerable thought to what would make the right vehicle choice.

In 1973 they had been running a big HQ Holden Monaro four-door for GM-H dealer Suttons Motors in Australian forest rally events, which had convinced them that a big car would have certain advantages over a smaller one in such a marathon.

It would have more space and be more comfortable. It would have plenty of ground clearance and could carry a lot more equipment without affecting its performance. It would also be stronger. And a large capacity, low-stressed V8 could retain its tune for longer than a high-revving small engine.

They were also acutely aware that weight was the absolute enemy of performance because every extra kilogram made the engine work harder, thereby using up more power and petrol and putting more load strain on the suspension. And most big cars (including their Monaro) were heavy.

Thanks to the release of the Leyland P76 V8 in mid-1973, though, their choice proved simple. Leyland’s new sedan combined mechanical simplicity with generous interior space. And it was lighter than its Ford/Holden/Valiant ‘big car’ rivals because it was built around an all-aluminium alloy 4.4 litre V8 (based on Rover’s 3.5 litre Buick-derived V8) that weighed no more than the Austin 1800’s four cylinder engine yet produced twice the power.

The P76’s unitary body was very strong as proven during Leyland’s extensive durability tests on the roughest outback roads during its development. It also featured supple, long travel, four-coil suspension ideal for rough roads, with McPherson struts in the front and a live axle located by trailing arms in the rear.

Other pluses were its rugged and reliable Borg Warner rear axle assemblies and gearboxes, along with big ventilated front disc and rear drum brakes designed for heavier cars that gave it good reserves of stopping power. The sharp response of rack and pinion steering was another bonus. It ticked all the boxes.

Preparing the P76

With their decision to go with the P76, Green and Bryson decided on a basic specification. It would need to be painted white to reflect the sun and reduce cabin heat. The mechanical menu was V8, four-speed manual, limited slip diff, quicker-than-standard steering ratio - and air conditioning.

Given the searing temperatures expected in the Sahara, they reasoned that if they were cooler they would be more comfortable. They would then require less drinking water, which would reduce the amount they had to carry. And the pressurised cabin would also stop dust entering, making it a nicer work environment all round.

Due to late confirmation that the World Cup Rally was going ahead, along with early production delays at Leyland caused by strike action and material shortages, Green took delivery of his P76 in Sydney just 10 weeks before the rally was due to start in London on May 5.

And as the car had to be given a shakedown before being flown to London no later than mid-April, Green and his small team had just over a month to prepare the car. What they achieved in such a short period of time was remarkable.

Leyland Australia’s management team was enthusiastic about the project because they had faith in their new creation. Its embattled dealers even passed the hat around to boost Green’s limited funding.

The company said it could not build a car down the line to Green’s exact specification but would allocate the most suitable model straight off the production line and provide Green and his small team unlimited technical help.

It was a white top-of-the-range Executive model with V8, air-conditioning, auto transmission and power steering. Leyland engineers advised that it would be easier to convert the top-spec model to a four-speed manual using swap-over factory parts, rather than try to retro-fit air conditioning to a lower spec manual version. They also advised that the power steering rack had the faster steering ratio they wanted, which could also be modified to operate without power assistance.

A small workshop was leased in Sydney’s north and two men were employed to work full-time on the car; qualified engineer and rally navigator Brian Hope and RAAF aircraft technician Paul Crotty. They were assisted by many enthusiastic volunteers, including some key Leyland engineering staff that pitched in after hours and on weekends to make sure the car was completed on time.

With the emphasis on minimising weight, the luxurious interior trim was stripped out including the internal door trims and instrument panel. Even the internal window winder and door lock mechanisms were removed, with side window glass replaced with lighter and stronger polycarbonate, and door locks operated by simple pull cords. All up that saved about 155 kgs.

The heavy steel bonnet and boot lid, being non-structural items, were replaced with lighter fiberglass mouldings that saved another 31 kgs. The heavy steel front and rear bumpers were also removed.

Brian Hope got rid of more weight by dispensing with the metal bonnet hinges and fitting a simple rubber flap across the nose of the car. This also provided full engine bay access because the front-pivoting bonnet could now be opened forward to a full 180 degrees. And because it rested in a cantilevered horizontal position like a table, it could serve as a large sun shelter if they became stranded in the Sahara.

All the heavy sound deadener compounds and materials were scraped off before Leyland’s top body man Roy Cullen spent a week re-welding all the seams and joins in the body shell for extra strength, including reinforcement around the front strut towers where the heaviest and sharpest shocks were likely. The door sills and other hollow structural box sections were filled with expanding polyurethane foam to boost rigidity.

The standard fuel tank fitted beneath the boot was replaced by two large fuel tanks used on Leyland trucks, each with a capacity of 90 litres, which were mounted inside the car’s huge boot. That added up to about 40 gallons, which given Leyland’s famous claims about being able to carry a 44-gallon drum in the boot seemed appropriate.

The first tank was mounted above the rear axle to keep as much weight as possible within the wheelbase; the second was mounted behind it on the stepped-down boot floor. An electric pump transferred fuel between the two tanks.

To maintain the best weight distribution, the second tank would usually only carry a small reserve and be filled only on very long stages. Apart from the two tanks, the boot was kept as empty - and therefore light - as possible with only a hand winch and cables, small axe and spade plus a few spares like air filters, fuses, light bulbs etc.

The stripped-out spacious cabin was fitted with a full roll cage made from lightweight alloy tubing plus rally seats, four-point seat-belt harnesses, sports steering wheel and a redesigned padded dashboard with instruments and controls thoughtfully positioned to best suit driving and navigating roles.

The stripped-out doors provided a wealth of internal storage compartments. The back doors held 9.0 litre plastic water containers, which not only increased the crew’s drinking supplies but could also clean the headlights and windscreen via a small electric pump and hoses.

The standard radiator grille and twin-headlamps were replaced with a stout stone shield and larger more powerful single quartz iodine headlamps. Another pair of long range rally lamps was mounted on a bar pivoted by an electric motor, which could raise or lower their lighting angle from the cabin.

A third pair of rally lights was installed on the roof when the event got underway.

To reduce weight on the front wheels, the 12 volt battery was moved from the engine bay to the rear of the cabin. And instead of a heavy bull-bar, Hope fabricated a light but strong space-frame from square steel tubing, which sat forward of the car’s nose to enclose all the lights and provide at least half a metre of crumple zone to the radiator.

From the all-aluminium V8 Green wanted strong torque more than brute horsepower, plus reliability in hot or cold weather for 17,000 kms without a noticeable loss of tune.

Leyland’s engine man Kjell Eriksen recommended keeping it at the standard 4.4 litres and if fully checked and assembled with great care said it would last forever. The engine was removed and sent to Lynx Engineering for a full blueprint, balance and crack-testing of all parts.

Leyland’s best engine tuner Noel Delforce then did the engine’s final preparations and was thrilled with the results on the dyno. The power output was roughly the same but the torque figure had greatly improved, peaking at just 2500 rpm. With a redline of 6000 rpm, maximum power was reached at 4250 rpm but could live at 5000 rpm all day.

The diff ratio was kept at the standard and relatively tall 2.9:1, because the engine’s lower revs would not only reduce wear and tear but also use less petrol. Therefore they would have to carry less of it, again reducing weight and improving performance.

Leyland engineers were confident their 4.4 litre V8 would have more than enough grunt to pull the 2.9:1 diff ratio. Green calculated that with the Borg Warner four-speed manual gearbox in place, Delforce’s safe 5000 rpm limit would give a theoretical top speed of around 200 km/h.

A robust toboggan-shaped aluminium guard was fitted beneath the engine to protect the sump and a twin exhaust system, which exited on each side of the car through the lower sills behind the front doors and tucked up neatly into floor recesses, was well out of harm’s way.

One of Green’s greatest concerns was the car’s standard suspension in such an event, as he was well aware of the extreme modifications on factory rally cars overseas that made them virtually indestructible. He was concerned that the Leyland people did not comprehend the severity of what lay ahead. Or perhaps they had so much faith in their new car they didn’t share his concerns.

Either way, the engineers suggested fitting heavier rear coils, mindful that it could be required to carry up to 180 litres (40 gallons) of fuel on rough roads. Armstrong also supplied larger rear shocks, but no stiffer than standard; they just had a greater capacity to cope with hard work.

Leyland also supplied specially-made front struts with thicker steel shafts, slightly stiffer coils and firmer damper settings, which still allowed generous wheel travel. The steel rims were also kept standard width, to avoid greater loads on the wheel bearings.

The standard front disc/rear drum brakes were fitted with heavier duty pads and linings. Leyland also modified the front-to-rear bias with more braking effort going to the rears. This was done at Green’s request to make it easier to ‘step out’ the tail during cornering, to make the car easier to handle at high speeds on loose surfaces.

With the build completed on schedule, Green just had time for a quick shakedown in some sandy roads in western NSW. The car performed without a hitch, but because of its tall gearing it went so quickly at low engine speeds that Green found it almost dangerously deceptive at first.

The four gears overlapped beautifully, with each shift at 4000 rpm dropping the next bang into the engine’s peak torque zone. He drove it through a known rally special stage near Bathurst, where in other cars he would struggle to average more than 70 km/h. The P76 did it at a loping 100 km/h. This was a very light and fast 200km/h rally machine that pulled like a train!

On his return to Sydney, Leyland stylists had enough time to apply a new coat of white paint then decorate it with an iridescent blue side stripe trimmed in gold reflective tape. The fiberglass bonnet was also painted blue, with patriotic gold stars representing the Southern Cross. Additional signage for major sponsor Faberge (Brut 33 toiletries) plus Endrust, Total, Avis and Travelodge were also applied.

The car made it to Sydney airport just in time to be loaded into the belly of an airliner and flown to London. With a modest sponsorship budget and time constraints, Green and Bryson had not been able to do a pre-event survey of the African section, particularly the Sahara, which would prove decisive.

And they could not afford a full service crew. Brian Hope would hire a van in the UK and either drive or catch flights to various service points along the way.

Leading the World Cup Rally

As the 52 starters assembled at London’s Wembley Stadium on May 5, the only full works entry was a Lancia Fulvia driven by East African rally star Shekhar Mehta.

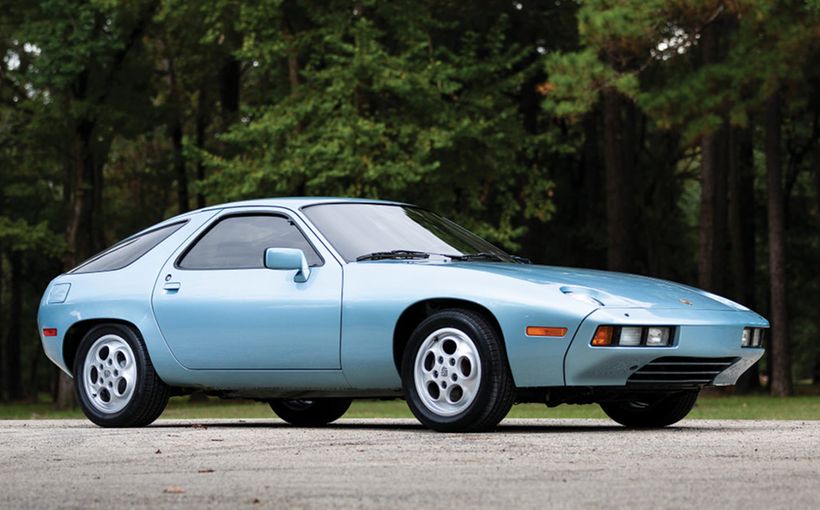

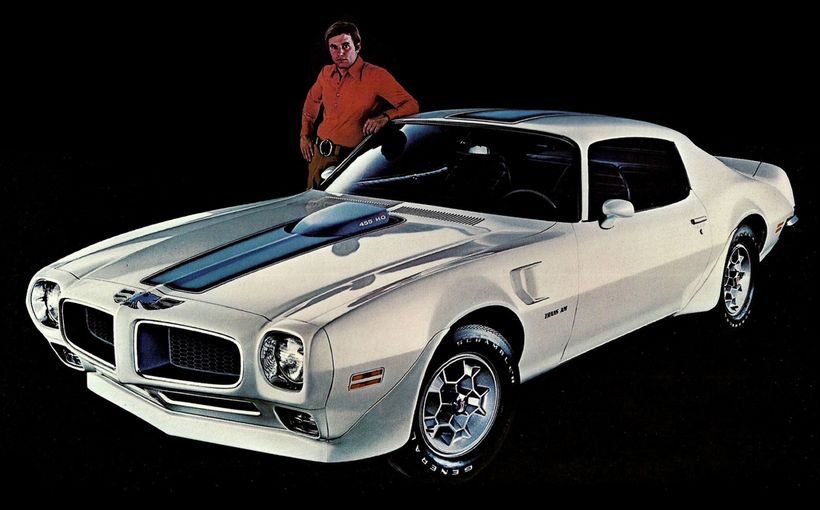

Other short-odds potential winners included 1968 London-Sydney Marathon winner Andrew Cowan in a Ford UK-prepared Escort RS2000 and Polish rally hard man Sobieslaw Zasada in a works-prepared Porsche Carrera. Even Grand Prix great Stirling Moss was there in a Mercedes Benz, plus several well prepared 4x4 Jeeps led by US off road racer Brian Chuchua.

French automotive giants Peugeot and Citroen also assisted with the preparation and servicing of cars for various entrants. These included another Aussie crew in a Citroen DS 23 which comprised Andre Welinski, Jim Reddiex and wily Redex Round Australia Trial winner Ken Tubman. They were not expected to set the early pace, but certainly be there at the finish...

From the start Zasada led in his Porsche, setting fastest times through special stages in England and Spain. Cowan in the rapid Escort RS2000 was second on points when they reached the Mediterranean.

The lone P76 suffered a simple fuel blockage on the UK stages that was easily cured, but it dropped the Aussies to third last in the field when they boarded the ferry at Southhampton to cross The Channel to Europe.

In Spain, though, the Aussies stunned everyone with the speed of their Leyland V8 sedan, moving up an astonishing 44 places to be placed eighth as the Algeciras-Tangier ferry shipped the rally field to North Africa. Only Zasada’s Porsche had been faster than the P76 through Spain.

A long and difficult section through Morocco in North Africa took a heavy toll on the field, with lots of mechanical breakages. The light and fast P76 came through with no problems, gaining another five places to be third by the time they reached Adrar on the edge of the Algerian Sahara.

It was here that both Zasada and Cowan stopped for lengthy services, putting the P76 into the lead as the field plunged south into the world’s greatest desert aiming for the next checkpoint at the oasis of In Salah.

It was a long night run on the track to In Salah. The P76, with its light weight, high ground clearance and ample V8 power, churned through the sand with consummate ease, averaging almost 110 km/h on its way to the checkpoint. Their theories about a big, powerful and light car in such an event were proving to be inspired.

At In Salah, the P76 was leading the event by more than two hours. Zasada’s Porsche had blown its engine in the heavy going and Cowan’s Escort had become badly bogged. Virtually every other car behind them had also become bogged or struck trouble. The Aussies could sniff a potential win.

Lost in the Sahara

A crucial flaw in the route instructions in the night run south from In Salah to the next checkpoint at Tamanrasset caused the leading P76 and many competitors behind them to become hopelessly lost. Some were stranded for two days. Some almost died from thirst.

In the dark of night, the 1974 World Cup Rally quickly descended into chaos. By the time Bryson had used his sharp navigational skills to chart an overland course to the correct track to Tamanrasset, the P76 had taken a fearful pounding escaping the towering dunes, resulting in a broken front strut.

Green spent a day stranded in the searing Sahara heat while Bryson hitched with another competitor to get help. He returned with fly-in mechanic Brian Hope and two new front struts which allowed the P76 to continue to Tamanrasset.

By that stage only one car had completed the entire original route to the southern-most point of the rally in Kano that was still in good shape – the Tubman/Reddiex/Welinski Citroen.

Tubman was one of only two drivers (Andrew Cowan the other) to have done pre-event surveys of the African leg, which proved a crucial advantage. However, the rear suspension in Cowan’s heavily-laden Escort had collapsed. Tubman in his indestructible Citroen now held a lead he would never relinquish.

The survivors were re-grouped for the formidable 2,200 km grind north-east to Tunis on the Mediterranean coast where the field would be shipped to Sicily for the start of the final leg through Europe.

Green and Bryson re-started in 19th place but their Sahara nightmare continued when another strut (which had been damaged in transit from London) broke in the Hoggar Mountains about 400 kms out of Tamanrasset.

To stay in the rally they spent three days driving (limping) the 1,800 kms to Tunis, across brutal terrain in a car that was very hard to steer with the front right corner slowly collapsing underneath them. At one stage the broken strut punched its way into the engine bay with such force that the coil spring ended up wedged hard against the engine! That alone took six hours of work to free.

It was a cruel fight for survival which Green later described as the most punishing drive of his life. However, with body repairs completed and another pair of new struts fitted in Tunis, the P76 was back in the game.

A Targa Trophy

Although now out of contention to win the event, the big Aussie sedan’s run across Europe was inspired. The high point was being awarded a special trophy for setting the fastest time on the famous 72 km Targa Florio road circuit in Sicily.

It was the same incredibly dangerous yet enchanting circuit which had hosted a magnificent annual sports car race since 1906 and which had only come to an end in 1974 for safety reasons. Leyland was so impressed with Green’s world-beating performance that it produced a special ‘Targa Florio’ limited edition model of the P76 which today is highly sought after by enthusiasts.

The P76 continued to show formidable pace as the field made its way to the finish line in Germany, also recording the fastest times on several special stages in Turkey.

Of the 52 cars that started the event in London, only 19 were classified as finishers in Munich, led home by the winning Aussie-crewed Citroen. The P76 was in 13th place.

If not for the shambles in the Sahara, one can only wonder where the P76 could have finished after leading one of the most gruelling motor sport Marathons the world has seen. Could winning the World Cup Rally have even saved the P76? Not likely, but sadly we’ll never know.

Protect your Leyland. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.