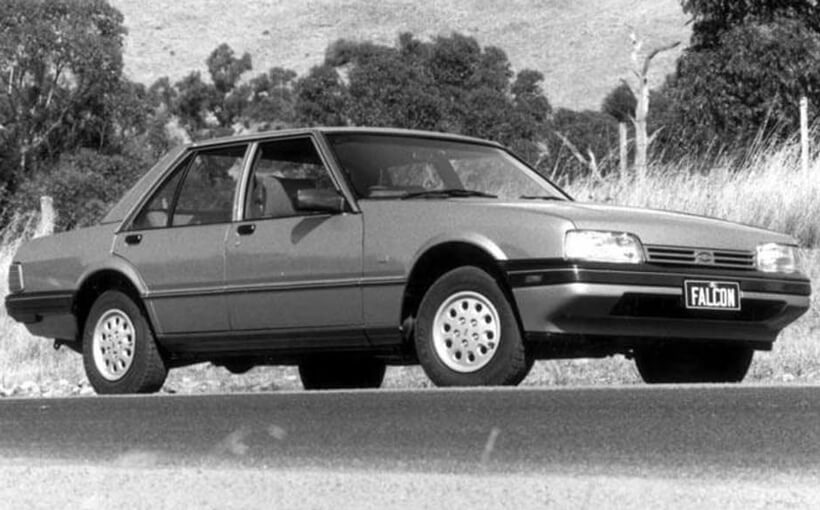

Ford XF Falcon: who could argue, Falcon WAS the answer!

To an industry outsider and even perhaps to a few of the invited motoring journalists, Ford Australia’s decision to showcase its XF Falcon at the Oran Park racetrack might have seemed odd. After all, in October 1984 it had been almost two years since the company had manufactured its final V8 engine and more than eight years since the demise of the legendary, unique Ford Falcon GT. High performance was no longer a Falcon brand value.

But there was an unpublicised tale to explain the decision to let the motoring media loose in the now six-cylinder-only Falcon at a closed venue. The previous year, at the launch of the Ford Telstar, one journalist crashed his car heavily with one of the company’s most senior executives in the passenger seat. No-one was hurt but the PR executives decided that their next major launch would not be conducted on public roads.

As it turned out, the Falcon was not too bad on the Oran Park South circuit. (I recall lapping in 62 seconds, which was reasonable for any standard production sedan running on street tyres not especially inflated for the purpose.)

There is always a problem with launching a new car at a racetrack, namely that those among us who love driving on them are prone to forget almost everything about the car in favour of savouring the experience. Arguably, with the XF this was a good thing: despite the predictable Ford Australia hype, there really wasn’t all that much about the XF that proved memorable

The XF was the second facelift on the 1979 XD. Hindsight clearly shows that it was the XD that set Ford Australia on its trajectory to market leadership. Of course, it was not so much the car itself, but the way those so-clever marketing executives drove the necessary engineering changes to be able to present the Falcon in the most favourable possible light.

The XE, which followed three years later, boasted a number of significant advances, chiefly a brilliant Watts Link six-link rear suspension in favour of semi-elliptic springs (euphemistically known as the ‘Hotchkiss System’), Weber carburetion and a five-speed gearbox option. In 1982 in a road test for MOTOR magazine, I found the premium Fairmont Ghia ESP considerably superior to a VH Commodore SL/X, even though the Commodore had a 4.2-litre V8 engine which gave the lighter car hugely better performance than the 4.1-litre sixpack Ford. Both cars had four-speed manual gearboxes (the five-speeder being limited at that stage to cars specified with the entry level 3.3-litre engine). The worse the roads, the greater the Falcon’s supremacy, truly the great Australian road car!

A great package and highly attractive visually, that ESP. So where was it when the XF arrived? Gone. Without the option of a V8 engine (and there had been two on the XD/XE – the 4.9 and 5.8), perhaps the savvy marketers decided the ESP might have seemed pretentious.

And so, to many of us, the XF Falcon constituted something of an anti-climax, despite all those memorable laps. But whatever we may have thought, the market continued to buy it in greater numbers than its arguably more advanced VK Commodore rival.

By the time the XF, codenamed ‘Redwood’, made its debut, Ford Australia had enjoyed market leadership for two and a half years. But the VK – the first Commodore with an injected engine option and boasting a new six-window glasshouse as the major element of a major facelift – was pushing Holden’s numbers closer to Ford’s.

The XF’s facelift was a reasonably half-hearted effort. Just as the XE’s nose was softened compared with the XD’s, so was the XF’s. But where the XE looked integrated, the XF’s rounded nose and lower bonnet line looked slightly out of keeping with the still rectilinear tail. The grille was new as were the slimline headlights. The new tail treatment was very effective (especially when colour-keyed), making quite a step up from the previous model in my view, though critics think it is fussy in a somewhat Fisher Price fashion.

Inside, the all-black dashboard of the XD and XE had been ditched in favour of a redesigned, colour-keyed panel. Digital instrumentation was enjoying its brief fad during these years and the premium Fairmont Ghia model shared its configuration with the Fairlane and LTD. The binnacle pod with its touch buttons for assorted functions including climate control and cruise suggested some influence from the Mazda 929 (as co-operation and model sharing between Mazda and Ford Australia flourished).

A fold-down rear seat hatch improved luggage-carrying but the proper split-fold rear seat would have to wait for EA.

An adjustable driver’s footrest was fitted to all Falcons.

More importantly for keen drivers, the steering wheel was moved closer to the instrument panel. The XE’s wheel had gone in a few centimetres but not enough; now a perennial complaint had been solved. Upmarket variants scored a steering column adjustable for rake.

All variants acquired additional standard kit. The Fairmont Ghia was the greatest beneficiary with cruise control, trip computer, fast glass, central locking and so-called Premium Sound System.

The EFI engine received a more advanced EEC 4 digital microprocessor and a higher lift camshaft. All engines got larger inlet valves, revised piston rings for reduced friction and an improved cooling system. The Honda-supplied alloy cylinder head was redesigned.

The 4.1-litre Weber-fed sixpack now made 103kW at 3750rpm, up noticeably from the XE’s 98 at 3800. Torque climbed from 305Nm to 316. Gains for the injected six were even greater – 120kW and 333Nm, up from 111 and 325.

The 3.3-litre six promised no more power or torque.

Taken together, these changes amounted to a fairly modest upgrade and, for enthusiasts, more was lost than gained. Despite all the Ford Australia rhetoric, the 4.1-litre EFI six was never going to substitute for the much love 5.8-litre Cleveland V8, even if it mostly had the measure of the 4.9 (which was, of course, thirstier). And the disappearance of the ESP (European Sport Pak) was most unfortunate.

The flagship LTD (and to a lesser extent the Fairlane) lost some credibility. This bastion of the hire car trade and Commonwealth Government fleet had achieved its apogee with the outgoing XE-based FD with 5.8-litre V8 engine, leather, Moonroof and highly regarded (at the time) Michelin TRX wheels and tyres. How could anyone compare a 4.1-litre EFI FE with velour trim and tacky digital instrumentation?

The XF had to soldier on for three and a half years until the much vaunted aero EA was ready for market (and, in truth, at launch it really wasn’t quite ready!). In 1985, 25 years of Falcons and 60 years of Ford Australia must have seemed like the perfect opportunity to offer a Silver Anniversary Falcon. The first cars off the line arrived at showrooms on 14 September, precisely one quarter of a century since the XK drove into town.

Two thousand of these special versions were produced, all based on the volume-selling 4.1-litre carbureted automatic sedan with T-bar shift. Two-tone colour combinations looked good and the unique trim was a significant improvement. There was also a colour-keyed grille, Fairmont taillight surrounds and LTD alloy wheels. The marketing executives had made the right call and this car sold well.

Unleaded petrol was mandatory in all new cars from February 1986. Performance suffered noticeably, despite Ford Australia’s claim that ‘Ford owners will find it hard to pick the difference’.

On 16 October 1986 Ford Australia introduced the model commonly referred to as XF ½. A five-speed manual transmission was finally offered with the bigger six, colour-keying freshened the exteriors. Most importantly, four-wheel disc brakes and power steering became standard equipment on passenger models. A Fairmont Ghia wagon with chrome roof rack was added to the range. Wow!

The Falcon continued to lead the sales race, helped in great measure by the fact that up to 70 per cent of the cars went into fleets and also by the fact that its utility and panel van no longer faced Australian-made Holden rivals. But even without including the popular utes and vans, the XF outsold its Commodore rival(s).

The Falcon wagon, built on the same wheelbase as the Fairlane/LTD, was a more substantial vehicle than its VK Commodore rival. Few customers seemed to be concerned about its continued use of semi-elliptic rear springs.

When the VN Commodore won the prestigious Wheels Car of the Year award in 1988, Ford Australia’s response was to advertise its sales figures, declaring Falcon to be the Car of the Decade. Frankly, no-one was left with the imagination to argue the point; the marketing department had won every debate.

Back in 1987 I was invited to write a piece on the Falcon, ‘Ford is the last bastion of Aussie car culture’, for the Melbourne Herald (evening newspaper), which was published on 15 July. By this stage, the XF Falcon was facing off against the Nissan-engined VL Commodore and, frankly, seemed dreadfully old-hat. I opined:

In the long automotive winter of 1979, as the fuel crisis finally entered the Australian consciousness, Falcons seemed to grow in the paddocks at Ford’s Broadmeadows headquarters.

Even the company’s most sanguine optimists believed that a mistake had been made in opting for a traditionally sized Australian sedan, powered by thirsty six or eight cylinder engines.

Eight winters later, that same basic car is still with us. But, no, it’s no longer growing in the paddocks; rather Ford Australia, the only consistently profitable carmaker in this overcrowded market, sells every Falcon it builds.

And, after two facelifts and a number of engineering refinements, the Falcon is Australia’s top-selling car, as it has been for all but two of the past 50 months.

Ford finally eclipsed Holden’s in 1982.

Since then a slim lead has been opened to the dimensions of a walkover: Ford one. Others also ran.

The Mazda connection has been a big factor, but the consistent sales success of the Falcon and its assorted derivatives must take much of the credit.

This year to date April, the company held 29 per cent of the total vehicle market, compared with 26.5 per cent YTD April 1985.

Back in 1979, the figure was closer to 20 per cent with Holden comfortably ahead. Back then Ford’s advertising looked slightly silly: if Falcon was the answer mused one wit, then it must have been a bloody stupid question…

How can it be that a car which experts agree is outmoded – even primitive – outsells more efficient newcomers? And why, for that matter, is the company that builds such a car, triumphantly number one in a difficult market?

The first part of the answer has to do with the automotive tastes of Australians, but I would suggest that the major part lies with the consistent intelligence of Ford Australia’s marketing.

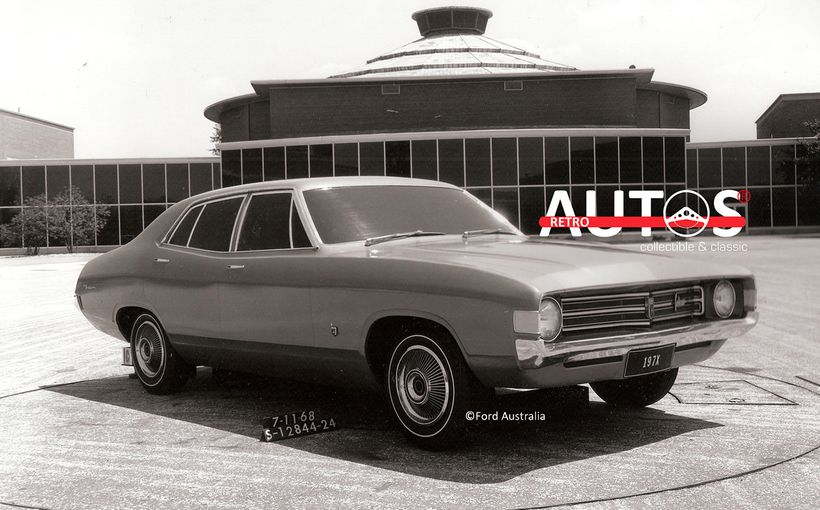

Let’s return to the woes of winter 1979. Holden’s had launched its European-based Commodore at the end of the previous year.

About all it had in common with with the old Kingswood/Premier range were engines and transmissions. The shape was contemporary and the car was lighter, more attractive and far more competent.

As soon as the Ford executives set eyes upon it, they believed that they had made a terrible mistake in electing to stick with a bigger, more conservatively engineered model; basically, the XD Falcon of 1979 was nothing but a new skin drawn cleanly over old mechanicals.

Ford’s director of sales and marketing, Max Gransden, is happy to admit that the majority feeling among the Ford executives was that Holden’s had made the right decision in opting for a smaller car.

The Commodore was about to supersede the Kingswood (the two sold side by side for about 18 months). The Valiant was venerable and unloved.

The traditional Oz sedan was heading for dinosaur status. The Falcon was simply a more attractive dinosaur.

At first, the market vindicated the Ford men’s anxieties, buying Commodore in preference to Falcon.

And then marketing offered a fine piece of lateral thinking. Since economy was the catchcry of the day, why not try to use it?

The Commodore was perceived by the public as more economical than the Falcon because it was smaller. But its engines were even more old-fashioned than the Falcon’s.

The marketing men at Ford decided that if – and it was a big if – they could establish the Falcon as being no thirstier than a Commodore, then they could once again sell its size and spaciousness as virtues.

Naturally, the rhetoric of high technology had to be part of the formula in that fuel-conscious era.

The company struck a deal with Honda and, lo and behold, the Falcon acquired an alloy cylinder head.

It made minimal difference to fuel consumption, but it was something fantastic to advertise; its presence demonstrated the company’s commitment to the theme of fuel efficiency and a hint of high tech to spice up the traditional Aussie recipe.

A neat little alloy badge saying ‘Alloy Head’ went on to the Falcon’s flanks and the sales curve picked up almost immediately.

With the question of efficiency somehow answered, buyers fell back into the Falcon. They were sick of four-cylinder cars anyway.

Why not go for more sheetmetal for the money? And, yes, surely Ford was right. The Commodore was too squeezy! From that point on, it seemed that Ford could do no wrong with its Falcon.

Meanwhile, Holden’s continued to do nearly everything wrong with the Commodore. The press might have deemed it the superior vehicle, but the public disputed this judgment.

So confident had Holden’s marketing men been back at the release of the car in November 1978 that they decreed that fleet sales of the Commodore would be held off for some time; effectively they handed this market to Ford.

The effects of that misjudgment are still being felt. One reason the Falcon still fares so well is that private sales (where Commodore is marginally stronger) have declined by some 33 per cent, while fleet sales are down only seven per cent.

(In 1986 Ford registered 66,436 Falcons/Fairmonts compared with 54,696 Commodore/Calais.)

There has never been a Commodore taxi pack either. Suddenly nearly every taxi was a Falcon and the owners told their clients how much they admired the car.

Ford’s marketing skill has maximised the Falcon’s success. Falcons were entered in economy runs (with the right engine and gearing) and performed well.

When sheetmetal for the dollar could be sold, then the Falcon’s size was italicised. When high technology held sway, why, look, the Falcon acquired a gee-whiz Watts Link rear suspension and a Weber carburettor.

And later it even offered fuel injection.

In June 1987 as the car market entered its bleakest winter in more than 20 years, the Falcon was being promoted as ‘a legendary six’ for very little more money than ‘an ordinary four’.

In truth, it’s an antiquated car that has survived the onslaught of high-tech rivals better than even Ford had expected.

I found this newspaper clipping in a scrapbook during my research for this story and I agree with it completely 31 years later. But the one proviso I want to add is that Ford Australia’s marketing executives in that era understood family car buyers’ aspirations better than we motoring journalists. Yes, the XF was an antiquated car in many respects (even before 1987), but it represented a better answer to more people’s automotive questions than did the VK Commodore or even the VL – how unfortunate that the much better EA (once it was sorted failed to capitalise on such a huge advantage.