Ford Cortina-Lotus Mk II: Jim McKeown, Rallying and The Marathon

When Jim McKeown started racing a lightweight fuel injected Cortina-Lotus Mk II in 1968, he had already established himself as one of the best tuners and drivers of small-bore Fords on the planet with his mercurial Lotus-Cortina Mk I.

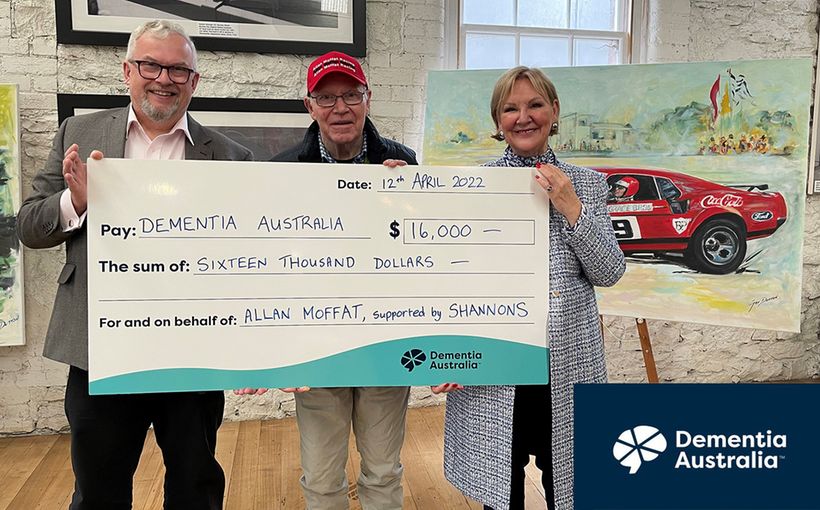

Since its debut in 1964, McKeown’s Cortina had been a stand-out performer with a staggering race winning ratio of around 90 per cent. It won numerous state touring car championship titles and smashed 1.6 litre class records at every track it raced on. Allan Moffat famously claimed Jim’s locally-developed Mk I was “the world’s fastest Lotus-Cortina”.

Not surprisingly, after four seasons in the Mk I, many expected the talented Victorian to progress to a new American V8 muscle car to tackle the heavyweights in the outright division including Pete Geoghegan’s ‘67 Mustang and Jim’s team-mate Norm Beechey in his Chevy II Nova.

However, Jim’s aspirations of stepping up to the big car class could not be realised under his long-standing contract with oil giant Shell, which through its subsidiary brand Neptune had backed the Neptune Racing Team since 1964, comprising Beechey (EH S4/Mustang/Nova), McKeown’s Lotus-Cortina and Peter Manton’s Mini Cooper S.

Shell, which in 1967 had replaced Neptune as the team’s naming rights sponsor, wanted to maintain that mix of large, medium and small cars in its famous three-car team to provide the broadest spectator appeal, which determined McKeown’s destiny in local touring car racing.

“The main problem was than ‘Jano’ (Bob Jane also had Shell backing) and Norm didn’t want me anywhere near a V8, neither did Shell,” McKeown told Shannons Club. “It was frustrating that I didn’t get to race a V8, but the Cortina Mk II deal was a good thing for me in other ways.

“I got the signing-on fee from Shell, plus the usual travel money for meals and airfares, plus bonuses for wins, extra bonuses for outrights and I got the car for nothing, so I did alright. And not many of the old racing car drivers did alright in those days, I can tell you that.”

Jim’s decision to replace his ageing Lotus-Cortina Mk I with the latest Cortina-Lotus surprised some, as the Mk II version was slightly wider and notably heavier (about 70 kgs) than its predecessor. It was also being built solely by Ford and was perceived to have lost some of its Lotus ‘panache’ in the transition. Even so, Ford Australia gave Jim plenty of good reasons to update to the Mk II.

“I actually wanted to race the new Ford Escort Twin-Cam because that looked like the right car to have in the 1600cc class,” Jim explained.

“Ford’s motor sport manager John Gowland said they weren’t selling Escorts here (until 1970) and wanted me to race the Cortina Mk II instead, because that was the car they were selling in Australia at the time (local production started in August 1967) and the car they wanted to promote on the race track and in rallying.

The Cortina-Lotus Mk II’s outstanding success in the Australian Rally Championship and astonishing speed shown in the 1968 London to Sydney Marathon, which are covered later in this story, are further proof of this car’s impressive motor sport credentials.

Building the Mk II

“Basically we had to incorporate everything we’d learned racing the Mk I into the Mk II,” McKeown explained. “It was a bit bigger and heavier than the Mk I, but with all those aluminium panels and lightweight magnesium factory parts, it was still a very light car (about 850 kgs).”

McKeown and his local development team comprised of what he described as “hillbilly mechanics”, based near Mount Dandenong in Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs, had already developed the Ford-based 1558cc engine with its two-valve DOHC aluminium Lotus cylinder head into a world beater in the Mk I.

With more than 190 bhp on tap, McKeown’s Cortina engine had 15-20 more horses than the best engines from European works teams. It had been stretched to its limits in every dimension, from dual 45mm DCOE Webers and high-lift camshafts to an enlarged baffled sump, Laystall steel billet crankshaft, Cosworth rods, wedge-top pistons, sky-high 13.5:1 compression ratio and staggering 8500 rpm limit.

However, under the bonnet of Jim’s Mk II was an engine displaying a distinctive ‘BRM’ plaque on the front of its aluminium cam cover. How Jim ended up with a cylinder head from the famous British Racing Motors organisation, complete with Lucas mechanical fuel injection, is a mystery today although Jim believes it was the result of his earlier dealings with Allan Moffat.

Moffat had famously borrowed Jim’s super powerful Mk I engine to compete in the 1967 Trans-Am series opener at Daytona in his ex-works Lotus-Cortina Mk I. Part of that deal was that McKeown would join him in a second car powered by Moffat’s BRM engine. Sadly a flywheel came loose on Moffat’s car and McKeown’s drive didn’t go to plan either in the cash-strapped team.

Jim returned to Australia after Daytona while Moffat stayed in the US to continue competing in the Trans-Am series. Jim said the two red and gold ex-Alan Mann works cars were loaded onto the transporter after the race and went back to Detroit with his hot race engine still installed in Moffat's car. He does not think that engine ever returned to Australia because he never saw it again to determine what caused the Daytona failure.

Back in Melbourne, Jim still had Moffat's standard BRM fuel injected cylinder head and spares left over from his 1966 race campaign.

"I guess Allan and I did some sort of deal," Jim said. "I recently asked him about this and he commented that this whole episode was just a blip in his long career and has been lost in time."

By incorporating all the big power secrets from his Mk I engine, McKeown’s Mk II was pumping out close to 200 bhp with improved throttle response thanks to the fuel injection. Even so, there were certain design elements that he was not happy with.

“I don’t think the fuel injection made it more powerful, but it sure opened up better,” McKeown said. “The Weber carbs used to get rejection and they’d be too rich down low and start to cough and splutter, whereas the injected engine would open up smoothly from about 4500 rpm which made it a bit easier to drive.

“The Lucas fuel injection had a throttle slide mechanism which was quite primitive. It was just a slide that bolted onto the cylinder head with four large holes in it and a big return spring. It had to slide against the intake vacuum of the engine and would stick if it got any grit in it, so I often had a jammed throttle.

“It was scary, particularly in the rain, so we just kept putting stiffer and stiffer return springs on it. The fuel injection was a high pressure system supplying a rotary metering unit driven by a toothed belt from the camshaft. The fuel flow was controlled by a rose-jointed rod connected to the throttle slide and a ramp-type cam at the back of the metering unit.

"The only way we could alter the mixture was to remove the cam, build it up with bronze, re-grind it on an emery wheel then test it on the dyno. It was crude I guess, but it worked."

With weight being such a critical factor in a car with only 1600cc to play with, McKeown was keen to adapt his close-ratio Holinger gear sets to the featherweight magnesium bell-housing, gearbox casing and extension housing supplied by his good friends at Ford.

The lightweight UK factory components included a magnesium diff housing, LSD and special ‘quill’ racing axles which Jim had never seen before. The inner halves of these tapered axle shafts were smaller in diameter than the outer halves, which allowed a slight twisting or torsion bar effect to reduce shock torque loads and therefore axle failures.

The Mk II Cortina-Lotus’s conventional leaf-sprung live rear axle was also seen as an advantage, after McKeown had struggled to improve the Mk I’s fancy but flawed rear-end courtesy of Lotus czar Colin Chapman with its coil-over shocks, trailing arms and central A-frame design.

Jim maintained that the Chapman design was “more a gimmick and part of his sales pitch to Ford” than a genuine performance enhancement. He said the A-frame’s altered geometry made the rear roll centre too low, which was why the early Mk I Lotus-Cortinas would lift their inside front wheels to alarming heights during hard cornering.

“We did a fair bit of work on the Mk II’s rear end, although I can’t remember the exact details of it. I think we made up some extra trailing arms so that there was no axle tramp and it put its power down well. We also played around with the spring angles to get the roll steer where we wanted it, so it was easy to control.

“When I look at the photos of it today, it looks very predictable and ‘chuckable’. You could throw it into a corner and it would lift the inside wheels in the air, but it was never an oversteerer or understeerer; it was very neutral in its handling.

“With those big Minilite wheels and the latest semi-slick Goodyear tyres which had fantastic grip it wasn’t a bad jigger, but it was still outclassed by the V8s as far as outright placings were concerned.”

1968 ATCC

McKeown certainly had the fuel injected Mk II in giant-killing form at Sydney’s demanding Warwick Farm Raceway during practice for the biggest touring car clash of the year - the 1968 Australian Touring Car Championship.

This was the final year the ATCC would be decided by a single race and the competition looked fierce. The mercurial Pete Geoghegan in his Castrol-backed ’67 Mustang was short-priced favourite to claim his fourth ATCC crown against his nemesis Norm Beechey in a new 350 cid Chevrolet Camaro and a mob of wild Mustangs driven by Bob Jane, Fred Gibson, Bryan Thomson and Kiwi stars Paul Fahey, Red Dawson and Rod Coppins.

Even so, McKeown upset the V8 hordes by qualifying fourth fastest with a scintillating time just 0.7 sec slower than the Castrol Mustang on pole position.

As expected Geoghegan galloped off into the distance and won as he pleased, as a high rate of mechanical attrition wiped out most of his V8 foes. Sadly, the long list of casualties also included McKeown’s Cortina, after it snapped a rear axle after only three laps.

“That was a real tragedy,” Jim recalled. “We didn’t have the good axles in it for some reason. With the latest Goodyear tyres on it, that car was amazingly fast at Warwick Farm given that it only had 1600cc against all those big V8s.”

The fact that a young Victorian by the name of Alan Hamilton suffered a flat tyre but still finished third, driving a new 2.0 litre Porsche 911 T/R in its first race, was not lost on McKeown. The speed and reliability of the lightweight flat-six European thoroughbred planted a seed in his mind that would soon grow into a long-term commitment to the German marque.

1969 ATCC

Proof of the growing popularity and importance of touring car racing was a decision by governing body, the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS), to expand the nation’s premier tin-top title from a single annual race to a multi-round series in 1969.

It was to be contested over five rounds in five states with a simple 9-6-4-3-2-1 point scoring system, which clearly favoured the fastest V8-powered cars as there were no extra points for class wins by smaller capacity machines like McKeown’s 1.6 litre Cortina or Hamilton’s 2.0 litre Porsche.

Even so, the smaller cars were still seen as a potential title threat, given the fragility of many V8 entries. McKeown didn’t get his ATCC challenge off to a good start at Calder where he scored no points. He also missed the second round at Mount Panorama in a dispute over starting money, but fourth place at Mallala and impressive thirds at Surfers Paradise and Symmons Plains saw him finish fourth overall in the championship.

By comparison, Alan Hamilton in his Porsche 911 T/R almost pulled off the greatest upset victory in ATCC history when he came within one point of beating Pete Geoghegan’s ‘67 Castrol Mustang, after a nail-biting final round in Tasmania.

Against Australia’s best cars and drivers, including the Jane and Moffat Trans-Am Mustangs and Norm Beechey’s new HK Monaro GTS 327, the little German car’s stunning speed and reliability produced one third and four second places from five rounds. McKeown could see his racing future in such a car.

“We had some great battles with Hamilton that year, but we just couldn’t hold his 2.0 litre Porsche over a distance,” Jim lamented. “If I drove the Cortina really hard for say 30 laps, it just wouldn’t finish in the same state as the Porsche, which ended up second in the championship.

“Towards the end I’d really lost interest in the Cortina. We were still breaking class records but by then it was all about the big guys up front. You’d be able to hang onto the V8s for a bit around a corner or in the wet, but in most places they’d just leave you for dead which was pretty demoralising.

“Given that under my Shell deal I couldn’t race a V8, the performance of Hamilton’s car in 1969 was the major reason I decided to switch to racing a Porsche in 1970.”

A champion rally car

The Cortina-Lotus Mk II’s relatively short competition career at the elite level in the UK and Europe was determined more by timing than anything else. Put simply, it was the right car at the wrong time.

In many countries the enduring reign of the Mark I Lotus-Cortina lasted until the end of the 1967 season, leaving little time for the Mk II to establish itself as its successor before the new smaller, lighter and faster Escort Twin Cam (released in early 1968) took over in both racing and rallying.

Initially, though, Ford considered it a better alternative to the untried Escort in long distance events like the East African Safari and 1968 London to Sydney Marathon, as its more generous dimensions provided greater comfort for crews and more space for carrying the multitude of spare parts and tools required.

In Australia the Escort did not go on sale until 1970, so the Mk II Cortina was Ford Australia’s local mid-sized weapon of choice for both touring car racing and rallying in the late 1960s. And in both 1.6 litre Lotus Twin Cam and 1.6 litre pushrod GT specifications it proved to be a fast and rugged rally car, easily claiming the 1968 and 1969 Australian Rally Championships.

In 1968, the first running of the ARC, Ford backed a three-car Cortina Mk II works team with top flight drivers including the company’s contracted race/rally tuner Harry Firth, rally specialist Frank Kilfoyle and Ford’s hands-on product planner Ian Vaughan.

Firth was driving his own bored-out and supercharged version of the Cortina-Lotus while Kilfoyle and Vaughan were in pushrod GTs featuring twin DCOE Webers, hot cams, big extractors, Salisbury Mk II LSDs and specialised rally preparation by Firth’s garage.

Competition between the Ford crews was strong but Harry had the ARC title sealed up before the final round, which he did not contest as he was busy overseeing preparation of the three works entered XT Falcon GTs for the London to Sydney Marathon.

For the 1969 ARC, reigning champ Firth was planning an even hotter version of his blown Cortina-Lotus, with a ‘stroker’ crankshaft to boost its capacity to 1840cc. According to Firth, the project was canned by competitions boss John Gowland on the grounds it would be unfair to his team-mates. It was of little consequence as Firth left in 1969 to join arch rival GM-H as boss of the new Holden Dealer Team.

His former team-mates Kilfoyle and Vaughan became Ford’s lead drivers for the 1969 ARC campaign armed with a pair of Cortina-Lotus Mk IIs wearing local GT side stripes. Kilfoyle was in sparkling form, winning the Classic, Warana and Alpine events to easily wrap up Ford’s second ARC title in fine style.

Roger Clark was in fast and fearless form in the Marathon, with reports of him passing cars on the outside of sheer drops and in mid-air as he maintained astonishing speeds. Sadly, even a works-prepared car could not withstand such punishment over such a long distance. Here Clark’s Cortina-Lotus is captured at full speed through Australia’s chilly Alpine regions. Image: www.flickr.com

Without doubt ‘the one that got away’ for the Cortina-Lotus Mk II was the 1968 London to Sydney Marathon, which thanks to the blindingly fast British star Roger Clark it led for most of the gruelling 16,000 km distance only to fail in the do-or-die final stages.

Ford assembled an impressive armoury of cars for the Marathon, which included several works-prepared Cortina-Lotus Mk IIs from the UK, Taunus M20s from Germany and a trio of Falcon GTs from Australia.

Clark and his Swedish co-driver Ove Andersson were the pre-event favourites in their works Cortina-Lotus Mk II and attacked from the outset with blistering speed, leading the first leg from London to Bombay which passed through 10 countries including England, France, Italy, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Indian coast.

After the depleted field was shipped to Perth to commence the final leg across Australia, Clark kept the pedal to the metal leading all the way to Port Augusta in South Australia before being forced to stop with engine valve damage.

Critics said Clark was pushing his car too hard, but the dashing Englishman knew only one way to drive – flat-out! To keep the fastest Ford in the Marathon, team-mates Ken Chambers and Eric Jackson donated the healthy cylinder head from their Cortina and withdrew from the event.

Given the Cortina-Lotus Mk II’s success in Australian rallying, the Ford works team prepared one of its ex-ARC cars for the burgeoning sport of rallycross at Melbourne’s Calder Park. Although this car was usually driven by rally champ Frank Kilfoyle, one of the sport’s most exciting confrontations occurred in 1970 when Allan Moffat did a one-off guest drive to take on the dominant Peter Brock in his supercharged HDT LC Torana GTR. Moffat not only set a new course record, but had the audacity to pass Brock over a jump on the last lap, colliding in mid-air with the Torana and breaking his Cortina’s side window, before going on to win the final! Note the crudely flared wheel arches to reduce mud splash and the nudge bar still fitted to the front of the car, which was perfect for giving Brocky a little hurry-up here and there. Image: Chevron Publishing

The stop for engine repairs had dropped Clark to third behind the Lampinen/Staepelaere works Taunus and Bianchi/Ogier Citroen DS 21, but with an incredible display of ten-tenths driving through the hidden dips, crests and washaways of the Flinders Ranges the Briton made up a staggering nine minutes on the leading Citroen.

Noted author Bill Tuckey, who was covering the Australian leg of the event with a TV crew, captured Clark’s resolute commitment in his wonderful book From Redex to Repco: “We were just below a blind crest that turned left in mid-air and dropped down to a right-hander into a dry creek bed full of rocks. Clark came over the top absolutely flat-out – maybe 160 km/h – with the car pointed the wrong way. He flicked it the other way, then the other way and arrived at the crossing dead straight and going back to third. By Brachina, Clark was back on time.”

By the time they reached Victoria, the German Taunus had suffered suspension damage and Clark was up to second place and only four minutes behind Ogier. However, his gallant fight-back came to a grinding halt at Omeo with awful noises coming from the Cortina’s rear-end. Some reports say the diff had failed, others claim it was a broken axle half-shaft. Either way, he could not go on.

They called him ‘Wild’ Bill Evans and he certainly lived up to his nickname during the 1973 rallycross season at Calder Park. Evans, who also starred for the Datsun works team in Class A at Bathurst for many years, dominated in his turbocharged Cortina, thrilling the crowds with high-flying aerobatics like this. The Cortina-Lotus Mk II certainly proved to have the right credentials to be a deserving rally and rallycross champion.

With his Ford service crew nowhere to be found, Clark wasted crucial time scouting the town in a desperate bid to find a solution. He managed to persuade a surprised Mk II Cortina owner to part with the standard components from his road car to repair the damage, but too much time had been lost and his bid for victory was over.

What made Clark’s demise particularly galling was that a Ford team mechanic had been assigned to service the works Cortina at Omeo. However, he had become involved in a drinking contest with the rival British Leyland team, so was very drunk and fast asleep at the control point when Clark arrived seeking repairs!

As a result, the London to Sydney Marathon was a classic ‘Hare vs Tortoise’ result with a surprised Scottish farmer called Andrew Cowan reaching the Sydney finish line first in a slower but very solid works-prepared Hillman Hunter. Had the Cortina-Lotus won, it would have been immortalised as a world beater.