Datsun 240K: the better Datsun with a royal connection

The Datsun 240K is one of those cars that seems to have acquired more respect with the passing of the years – or, more accurately, the decades. Picture the Australian automotive context of 1973 when this somewhat odd looking coupe made its debut, in amongst the HQ Holdens, XA Falcons, VH Valiants and the aftermath of what I like to call the supercar superscare (resulting from a 25 June 1972 article by Evan Green published in the Sun-Herald: ‘160 MPH Super Cars Soon’).

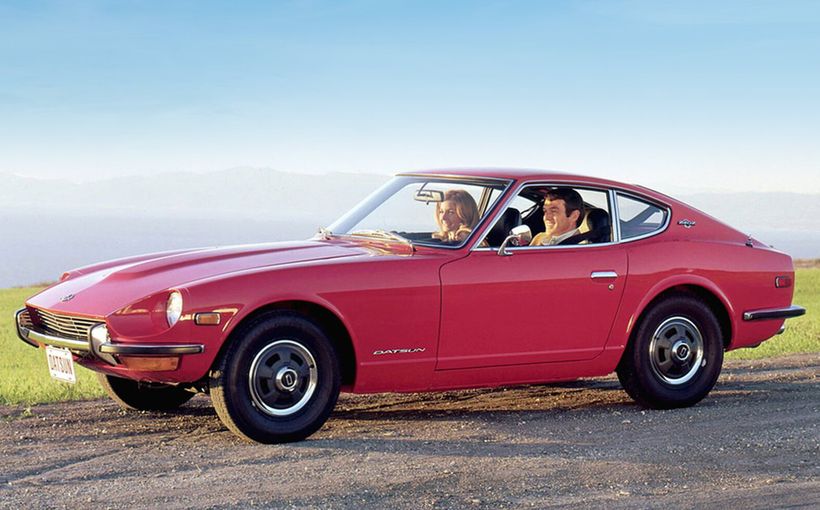

In 1973 Datsun was presenting itself as an almost schizophrenic brand. On the one hand there was the wonderful, evocative and fast 240Z. On the other was the boxy 1200 sedan, soon to be superseded by the 120Y, perhaps the ugliest and least charismatic small car of all time. Superficially, the 240K seemed to represent a kind of amalgam of these very different Datsuns, the 240Z and 120Y: it was ugly in something of the manner of the 120Y but with much of the driver appeal of the 240Z.

The best way to approach the character of the 240K is to think about what kind of company Nissan was in the late 1960s and very early 1970s. That adjective ‘schizophrenic’ is accurate in this sense: in 1966 Nissan merged with the Prince Motor Company. The Japanese automotive industry was just coming of age and the Government recommended mergers between companies to give the industry the strength to resist foreign takeovers. So that year Nissan got together with Prince, while Toyota merged with Hino (remember the Contessa, which the late Bill Tuckey described as understeering and oversteering at the same time?) and Daihatsu.

Wisely, Prince was permitted to operate independently. Prince’s hero car of the mid-1960s was the Skyline GT which was developed specifically for the second Japanese Grand Prix. Although a Porsche 904 won that 1964 race, the new Skyline GTs filled second to sixth places.

The roadgoing Prince Skyline GT was effectively a production version of the racer with a highly tuned 2.0-litre triple-Webered 2.0-litre single overhead camshaft six-cylinder engine. Maximum power was 127 brake horsepower.

The Skyline GT was a fascinating car. When it was conceived, Prince had two main models, the four-cylinder Skyline sedan and the six-cylinder Gloria luxury car (as strange in its way as the Hino Contessa). The engineers took the Gloria’s G7 engine, fitted triplecarburettors, tuned it mercilessly and mounted it in the Skyline. The body had to be stretched eight inches to accommodate the long in-line six, all of them ahead of the A-pillar. This stretch was not in any sense a cosmetic exercise – beauty being the last thing on the minds of engineers focused on success in touring car racing.

On 17 April 1964 the Ford Motor Company unveiled its Mustang, arguably the most significant post-war styling exercise. The Mustang’s trademark long bonnet/short boot theme has come over the next half century to represent a powerful rear-drive theme, the idea being that the length ahead of the windscreen and leading edges of the front door is necessary to accommodate the powerful engine. Of course, the Mustang, running on Falcon six-cylinder and V8 engines did not need that extra length (and nor did the 1968 HK Holden!), but the Prince Skyline GT did. If it resembled any previous four-door sedan in its proportions, that car was the 1955 Bristol 405.

The Skyline name was first used in Australia in September 1964 when the four-cylinder Prince Skyline made its debut priced at $1996. In the spring of 1964 the small Prince company offered Australian buyers the humble Skyline and the plush, extravagantly styled six-cylinder Gloria which cost $3028 at a time when an EH Premier was $2840.

The 1964 Prince Skyline GT is the true progenitor of the (C110) Datsun 240K, sold in other markets as the Skyline 240K and produced from 1972 to 1977. Two examples of the Skyline GT fared well in the 1965 Sandown Six-Hour Race, the second and last running of the event that would eventually re-emerge as the Sandown 500.

Prince’s independence remained real, not illusory, and lives on even now in the Nissan GT-R. In Japan, if you wanted to buy a Skyline you had to go to a Nissan Prince dealer, the car being unavailable from a Nissan dealer. Such a nicety did not apply in Australia when the 240K went on sale. Neither the Prince name nor the Skyline badge adorned its unlovely body. It wasn’t even a Nissan in branding. This meant that the proud Prince heritage could not be used to sell the 240K, which was unfortunate for those who recalled the original Skyline GT and its fourth placing in the 1965 Sandown event.

The March 1973 edition of Wheels included a road test of the 240K. ‘Forget the styling and drive it’ said the sub-heading on the contents page. Turn to the opening double-page spread on pages 14-15 and the heading is: ‘At last Japan builds a sedan that really handles DATSUN 240K: GO MACHINE’. Then comes the introduction:

So the styling is peculiar, you don’t notice that from behind the wheel as the latest Datsun GT heads an Alfa through your favourite bend.

The story then begins:

Datsun slipped the 240K on to the local market without a great fanfare. We first saw one on a truck hidden among a batch of nondescript 1200s and a couple of days later two pictures and a blurb arrived in the mail.

It looked just like any other Japanese coupe. Ugly, apparently superbly equipped, but over-priced for what it did. We dismissed it as a gimmicky car for the freds who are taken in by tinsel.

It was a good introduction. Then, a couple of paragraphs later, we are told why the 240K ‘comes remarkably close to achieving GT status’:

How? First the 240K isn’t a Datsun. Well, it is, and it isn’t. Actually it is a product of the old Prince engineers and is built in what was the Prince factory, before Nissan took over a few years back. Prince always did build cars with above average roadability and performance. They were enthusiast-orientated cars.

While the 240K does combine Datsun bits, including the ohc six-cylinder engine from the 240Z and 240C and a refined version of the 240Z/180B rear suspension, it has been developed by Prince.

Initially, the 240K came in one guise only, the hardtop with a four-speed manual gearbox. The price was high at $3947, a little more than an HQ Premier with the 308 V8 engine. Datsun was pitching the 240K as ‘a step up from the ordinary sixes’ (see the advertisement shown here: ‘Introducing a Masterpiece’), but it also seems that the 240K was intended to steal sales from European offerings like the Peugeot 504, Fiat 132 GLS and Triumph 2000TC, all of which were dearer. These cars were closer in dimensions to the 240K than were the (much wider) HQ Holden and its direct rivals. Of course, there was the cumbersome 260C as a Premier/Fairmont/Regal alternative, but the 240K had a sporty appeal entirely absent from that machine.

Arguably, before the introduction of the Datsun 240K, most Japanese cars sold in Australia were either entry level models or cumbersome luxmobiles such as the Toyota Crown and Datsun 260C. But even this categorisation has difficulty accommodating the radical Datsun 1600… Certainly, it was Prince and Datsun cars that were forcing Australian observers to re-imagine the Japanese automotive industry in the 1965-1974 time frame.

The 240K’s styling shows heavy Chrysler influences which sit uneasily on a car that does not have the luxury of expressing itself over nearly six metres of length; the four-door sedan is more resolved than the coupe, because it looks less like a Japanese caricature of 1967 Chrysler themes (as epitomised by the Newport coupe).

In April 1974 the sedan variant was introduced with the choice of manual or three-speed auto. Two years later, the two-door 240K got a five-speed manual.

Despite carrying ‘240K GT’ badging, the car was sold under the ‘GL’ heading to appease insurance companies. It was a time when any car called ‘GT’ or ‘SS’ automatically attracted inflated premiums.

Those opening paragraphs of the Wheels road test raised expectations rapidly only to lower them in the conclusion. The styling was pilloried and so was rear vision (spoilt by the C-pillar, not pillor!). Even the finish was judged ‘below the usual standard from Datsun’.

While the handling was good, the 240K suffered from the vague recirculating ball steering system that was the norm for Japanese cars of the period. But it wasn’t as bad as many peers. And the steering wheel rim which looked exactlylike real wood (unlike that fitted to the original Monaro GTS of 1968), constituted a lovely touch, in contrast to the obviously faux material described as ‘woodgrain’ which was applied to the dashboard. Said Wheels:

The steering is tighter with just one inch of slack at the straight-ahead and with a variable ratio it is accurate with good feedback to the driver and plenty of feel once on the move and through the slightly heavy stage at parking speeds.

In 1973 even V8 Holdens and Falcons were rarely specified with optional power steering. Certainly the 240K was lighter to steer than my father’s HQ Premier 253, for which he should have specified power assistance which was still a novelty for Australian car buyers, except those in the market for up-spec Mercedes, BMWs, Jaguars or the Aussie Ford LTD/Landau launched at about the same time as the 240K. (The ZA Fairlane 500 had power steering as standard from its launch in 1967.)

The Datsun’s performance was strong with a top speed of 110 miles per hour (one short of the old Skyline GT’s!) Because the 240K was heavier than its 240Z sibling – should that perhaps be cousin? – and used a single carburettor rather than twins, its acceleration was impressive rather than brilliant. The standing quarter-mile took 17.8 seconds, which was slower than the Premier 308 but at least half a second quicker than the same car equipped with the 253 V8.

Perhaps the 240K was launched here initially only in hardtop guise as a response to the Monaro and XA Falcon Hardtop, but the six-cylinder Datsun could not compete on performance with any of the V8s on offer except GM-H’s 253, while the 240K’s dynamics and brakes – at least until the arrival of the XB later in the year (1973) – were superior.

Modern MOTOR had a 240K test in its May 1973 edition. Rob Luck, the then editor, seemed quite pleased to describe it as the ’24-OK’ but history has not honoured his terminology in the way it has kept 24-ounce in the memory for the 240Z. I wish I knew who was responsible for that clever coinage. Luck’s major criticism was the small size of the boot and the difficulty of loading it.

The 240Z was recognised as a potential classic decades ago, but the 240K’s status as a collectible is more recent. But the same can be said of so many 1973 cars including the HQ Holden itself and the Ford LTD/Landau siblings. It may be stating the obvious, but as current cars grow ever more similar and difficult to distinguish from each other at a distance of 50 metres, odd-looking cars such as the 240K – so very 1970s in concept and execution! – grow more appealing. But I don’t expect the 120Y ever to become desirable to those of us who think nostalgically of the cars of the 1960s and 1970s.