Datsun 1600 Heritage Lives on in Bluebird

A pretty desperate advertising slogan was used by Nissan Australia in 1981 to promote its new Datsun Bluebird. ‘The first four-cylinder limousine’ was far from being an accurate description of the car with which the Nissan Oz executives hoped to take leadership of the 2.0-litre sedan sector from the Mitsubishi Sigma. Impressive pictures showed a man inside what looked like a huge cabin but in fact this was a particularly small man!

A wiser approach might have been to describe it as the most Australian Japanese Car. That’s because it was subjected to more local testing than any previous Japanese car sold here. But not everyone in 1981 thought ‘Australian’ necessarily equalled good as the quality of many locally manufactured cars was, er, poor.

Nineteen eighty-one was not one of the great years for the local industry. From the late 1970s on, sales reps had been taken out of their six-cylinder Falcons and Commodores and squeezed behind the wheels of supposedly more economical 2.0-litre four-cylinder models – Sigmas, Coronas, Datsun 200Bs and the like. The new Bluebird was developed with extensive local testing to seize a significant share of such sales, while also being intended to appeal to private buyers.

Long queues at petrol bowsers and odds and evens days for buying fuel had focused Australian attention on fuel economy like never before. I remember it all too clearly. In November 1978 I had bought a brand new Commodore 4.2 ‘Sports Pak’. Months later, sales of V8-engined Commodores, Falcons and Kingswoods slowed dramatically. I even found myself wishing I had bought a 3.3-litre sixpack variant instead!

n the winter of 1979 it was difficult to recall that the era of the Australian muscle car was only a few years behind us. The very term ‘V8’ was almost a dirty word. Owners panicked out of their Holden Statesmans and Fairlane Marquis at a huge loss just to get themselves behind the wheel of something that would use less fuel. It seemed at the time as if the age of high performance cars had already passed.

This was the context in which the Nissan Australia engineers developed the local version of the Bluebird. It was to be manufactured locally under the 85 per cent local content rule which enabled it to be brought to market at a competitive price. Tariffs on imported cars were running at 57.5 per cent.

The timing was interesting in another respect, too. Front-wheel drive was starting to supersede rear-wheel drive as the orthodoxy first in small cars and then in medium cars. When the Bluebird was introduced in May 1981, the Datsun Pulsar, Mazda 323 and Mitsubishi Colt had all made the switch to front-wheel drive, while the Corolla, Gemini and Escort stuck with rear-drive. It was still (just) possible in May 1981 to describe rear-wheel drive as ‘orthodox’.

As for the sales reps they are said to have hated their new four-cylinder cars with a passion. They drove them within a centimetre of their lives, consuming as much fuel in some cases as they had in a Falcon or Commodore. And of course the whole of life cost of running a Sigma or Corona turned out to be much the same as for a six-cylinder car, due to higher maintenance costs.

The perceived differences between four- and six-cylinder cars had changed a lot since World War Two. When Ken Tubman won the first Redex Trial in 1953 in his 1.3-litre four-cylinder Peugeot 203, the idea that any car with fewer than six cylinders was not suitable for Australian conditions was overturned. The sales success of the Volkswagen Beetle later in the decade confirmed this reappraisal.

But the stifling Australian Design Rules emission legislation meant that late 1970s four-cylinder cars were mostly gutless with a 2.0-litre engine unable to supply the performance of a ‘dirty’ 1.6. The term ‘four-cylinder’ again acquired negative connotations, just as it had back in the days of the Austin A40 Devon, which for a few years was Australia’s top-selling car before GMH could meet demand for the Holden.

Coming after the Datsun 200B and 180B, the new Bluebird was revelatory. It used an Australian-manufactured rack and pinion steering system from the same company (TRW) which supplied Holden for the Commodore. With this superior steering, well developed suspension, and excellent rough road ability, it felt like a new generation, almost as much of a change as from the pre-Radial Tuned Suspension Holden HX to the HZ. Some of the Nissan Australia execs attending the media launch of the Bluebird wanted to convince the journalists that the Bluebird represented the same kind of forward step as had the Commodore from the Kingswood.

Its 180B and 200B predecessors were launched with roughly 70 per cent local content which was gradually lifted towards the 85 per cent mark which attracted the lowest duty regime. But the Bluebird was 85 per cent local from the start.

The July 1981 edition of Wheels magazine had a feature story by Bob Murray called ‘Wings across Australia’. Murray and two other staffers drove an ‘electric everything’ Bluebird LX from Adelaide to Darwin and back. Murray reckoned the only imported components in that car were the Nissan five-speed manual gearbox and the rear axle. The only modifications it received were radiator and sump guards, four driving lights and sticky tape to disguise the Bluebird badges. Into the boot went some common spares, an extra wheel and tyre and jerry cans. It was serviced and got new tyres at the halfway mark.

Only the ‘four-cylinder limousine’ LX variant got the five-slotter with the lesser GX using a locally manufactured Borg-Warner four-speed gearbox, which had to travel on a truck from Albury to Clayton, where Bluebirds were made in the old Volkswagen factory.

The LX got electrically adjustable exterior mirrors, central locking, power windows and four-wheel disc brakes. There was tilt adjustment for the cushion of the driver’s seat. But air-conditioning was still an option. This was a high level of equipment for 1981 and helped justify the ‘four-cylinder limousine’ line. These days we would hardly classify it as ‘electric everything’; how times change.

Another Bluebird claim to fame was the polypropylene resin dashboard. It was the first to be fitted to an Australian-manufactured car. But I don’t reckon the Wheels team spent much of their time while cruising at 160km/h thinking about polypropylene resin!

On the stretch from Alice Springs to Tea Tree, the Wheels crew covered 209km in 75 minutes, a true average of 160km/h in the test LX. That was absolute pedal to the metal stuff. In pure performance this 1981 2.0-litre Datsun was about the same as its 1968 Datsun 1600 predecessor and that could only be seen as a good thing at the time. Here’s the point: Datsun Australia’s offerings deteriorated through the 180B and 200B era with at least one pundit quipping that ‘180B’ stood for 180 Blunders, while the 200B had 20 more. They weren’t nice cars, those Datsun Blunderbusses!

This journey from the 1968 Datsun 1600 to the 1981 Bluebird tells us plenty about that era of motoring. At every other time since the beginning of the automotive industry, cars have continually got faster. But the Bluebird, which was on a par with other 2.0-litre cars of the day for acceleration and top speed, took 14 seconds to reach 100km/h and 19 for the standing 400 metres. While the acceleration was no better than the 200B’s, the exhaust note was about 300 per cent superior; the Bluebird even had a slightly sporty note.

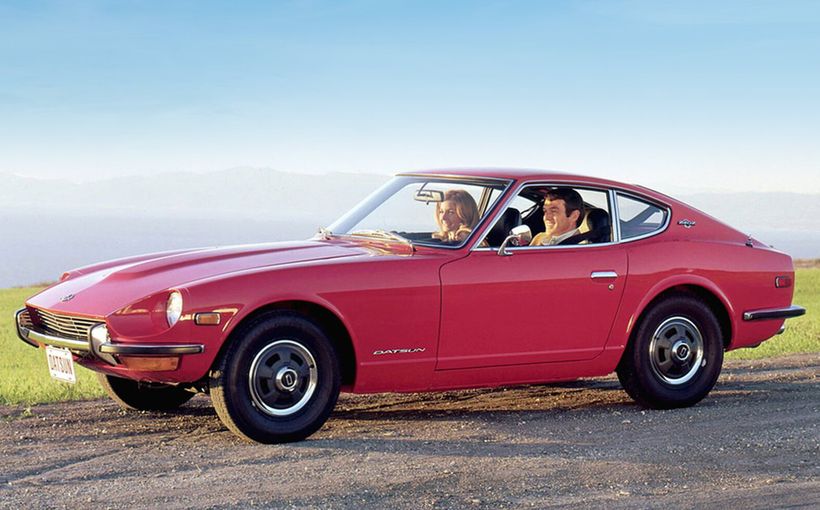

Was the Bluebird named for the purported bluebird of happiness or for Sir Malcolm Campbell and son Donald’s record-breakers? I can’t say. But fast the Bluebird was not, not at least until it acquired a turbocharger and went to Mount Panorama. The reprise of the Bluebird name, which hadn’t been used in Australia since 1968 when the 1600 replaced the last of the old straightened-out banana Bluebirds, was a bit strange and perhaps the result of a Japanese dictate, as was the later use of the unfortunate name ‘Tiida’ to replace ‘Pulsar’.

Nineteen eighty-one is a long time ago. In 1981 carburettors were still the most popular way of mixing fuel and air. Electronic fuel-injection was still two years away from being introduced on the Ford Falcon and it was generally offered only on expensive European cars. The Bluebird used a single carburettor and its maximum power of 69.9kW was slightly above average for a 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine. Its main rivals were the Corona (58kW), Mazda 626 (61kW) and the Sigma (64.4kW). The Sigma was the top seller and it was also available with a 2.6-litre four. Power steering was not offered and wasn’t in fact necessary. The optional air-conditioning was excellent for the era.

Remarkably, the brand new 1981 Bluebird could not surpass the performance of its legendary forebear, the Datsun 1600. But this was a sign of those depressing times. The quickest four-cylinder sedans of late 1960s included the Datsun 1600, Fiat 125 and Hillman Gazelle. Their levels of performance would not be eclipsed until the mid-1980s. When the Bluebird made its debut, Australia was still emerging from the grim days of ADR 27a which came into force on 1 July 1976. That was the day Holden introduced the HX, which was thirstier and slower than the HQ of five years earlier. It was the era not of progress but of regress, summed up by the ubiquitous and useless so-called econometer. So many 1981 cars had these, including the VC Commodore; it was literally a gauge of the times.

The Bluebird pointed to the future of the locally developed Mitsubishi Magna and Nissan’s own Pintara and Skyline. At least one Bluebird prototype was tested over 240,000km in the tough country of central Australia. Nissan Australia sent a team of engineers to Broken Hill, where they developed spring and damper rates, sway bars, suspension bushes and strut insulators to enable the new car to handle local conditions, at least up to a certain speed. Dust insulation also received attention.

The biggest single mechanical improvement over its predecessors was the change from recirculating ball to rack and pinion steering. Wheels said it approached Commodore levels of ride comfort and was well ahead of the Sigma, which had dominated the medium sedan segment since its 1977 debut.

Although the Bluebird was barely larger than the Toyota Corona, Sigma and Mazda 626, it offered more interior room with better all-round vision. The locally developed seats were larger in the front and offered superior support. They were also mounted higher in the car which had the effect of increasing legroom.

In June 1982 Nissan Australia introduced the sportier TRX variant, but like so many supposedly hotter cars of the time, it did not receive any extra power. What it did get were 15-inch alloy wheels, up from the LX’s 14-inchers and the 13-inch steel poverty pack wheels used on the entry level GX. And it also got the LX’s five-slot manual and rear disc brakes. New interior trim and more comprehensive instrumentation followed the sporty theme. Front and rear spoilers and a centre-mounted roof aerial (so cool!) completed the package. Oh yes, it also had a lower final drive ratio for marginally quicker acceleration. But don’t be fooled: this was a half-hearted exercise. It was the Bluebird equivalent to the old 200B SX with a fair bit more show and no significant extra go. Wouldn’t it have been great if Nissan Oz had offered the Japanese SSS two-door hardtop?

Fifteen months further down the bitumen calendar the Series II was released. New rear tail lights, a shovel nose and colour-keyed bumpers were the biggest changes.

The carryover 2.0-litre engine was the least convincing element of the Bluebird. Despite improved sound insulation, it was still a little harsh and noisy – despite the much improved exhaust note – when revved hard which it needed to be to yield reasonable acceleration. I guess those Wheels guys had the sound system cranked pretty high as they cruised at 160km/h which the non-existent tachometer would have shown as 4500rpm in fifth. Amazingly, the speedo was accurate, fixed on 160!

Yes, there was a high level of Australian input into the Bluebird but the locals didn’t get their way on all issues. The most glaring example was NVH at higher speeds. Local executives such as Howard Marsden had tried to convince their Japanese counterparts about the need for cars to cruise quietly at 130km/h or more. But because most Australian states had speed limits of 100 or 110, they refused to spend the time or money to develop NVH to suit higher speeds. The car handled extremely well until pushed to illegal speeds when the ride was softer than the Aussie engineers had wanted it to be. Yes, the suspension was calibrated locally but Japan still had the final say and the Bluebird was never designed to cruise at high speeds.

Within a year or so of the Bluebird’s debut this was addressed. The story goes that Japanese engineers, most of whom had never driven much faster than 80km/h in Japan and had never seen a dirt road, had numerous high speed crashes on the roads of outback Australia, with white-knuckled Aussies riding shotgun!

And so the already quite good Bluebird got that bit better, paving the way for the four-cylinder Nissan Pintara and six-cylinder Skyline which would be the last of the mid-size rear-wheel drive Japanese sedans developed as unique local models.

In April 1985 the Series III brought minor styling changes but the more powerful Nissan Gazelle engine with two spark plugs per cylinder. This took power up to 78kW, while torque climbed from 152Nm to 160. Performance was, of course, better, but four years had elapsed and many other cars had made more impressive gains. And the Magna was due with its wider body and improved 2.6-litre engine developing 85kW of power and 198Nm of torque.

Re-reading Wheels road tests of the time and reflecting back on my early years in motoring journalism, I’m struck by the fact that the Bluebird arrived on the scene about 18 months before Audi showed its brand new 100 sedan at the Paris Salon. With its mooted drag figure of 0.30 (it was actually more like 0.32 in road trim), this car gave notice to other manufacturers. While 1981 road tests rarely even mentioned aerodynamic efficiency, the following year it was very much the next big thing. The Bluebird, like most of its contemporaries was not designed to cleave its way through the air smoothly. That 160km/h top speed might have become 170 with a sleeker body.

So in many respects the 1981 Datsun Bluebird looked more to the past than the future. With a carburetted engine, rear-wheel drive and a comparatively narrow body, it had lots in common with four-cylinder cars of the 1960s. By the time the Pintara replaced it in 1986 it looked – and was – seriously dated.

Just a few years ago we might have thought of this Aussie Bluebird as just another old car but as we increasingly value our unique motoring heritage we can see it as a minor classic, an interesting local take on a Japanese car. With car manufacturing in this country due to end within years, machines like the Datsun Bluebird will only become more attractive. If you’ve got one in the shed, treasure it.