Volvo 240-Series: Formidably Safe but Insufficient Progress Everywhere Else

It is a difficult to think of any other marque that suffered such a loss of following among car enthusiasts as did Volvo between 1962 and 1975. In 1962 the B18 Amazon went on sale here in limited numbers, known initially as the ‘Volvo B18’ (‘122S’ came later) and quickly established itself as an outstanding semi-sporting car of great quality and unique character. But by 1975 when the Volvo 240-Series arrived in Australia, the marque had acquired an entirely different reputation.

What had gone wrong? It is a simple question with a complex answer. The early postwar Volvos were simple, rugged cars that were perfect for rigorous Scandinavian conditions. The PV544 combined shrunken US styling themes with great strength. It did well in rallying. Its Amazon successor was more stylish, plusher and had greater appeal on international markets. This car which is best known as the 122S was, essentially, a sports sedan. In among the Peugeot 404s, Fiat 2300s, BMW ‘Neue Klasse’ sedans and even the Jaguar Mark 2 2.4, it was a real contender, especially in the 1962-67 time frame, before such cars as the Datsun 1600 and Fiat 125 rewrote performance expectations for medium-sized four-cylinder sedans.

In 1967 Volvo introduced the boxier 140-Series with styling along the theme of the Hillman Hunter and Mark 2 Ford Cortina. It was a larger, heavier and much safer car than its 120-Series predecessor but offered no significant increase in performance. Although the 140 did well in rallying, Volvo’s semi-sporting reputation had effectively evaporated, replaced by widespread recognition for the marque for its incorporation of Daimler-Benz-like levels of safety, but without the accompanying grace.

The big problem here was that Volvo’s idea of safety seemed to be all about protecting occupants in a crash rather than helping the driver to avoid that crash in the first place. The emphasis all seemed to go on secondary, rather than primary, safety.

When I say ‘problem’, I am referring only to the company’s reputation among driving aficionados since Volvo’s market share in Australia continued to grow. There was no questioning the car’s quality and the 140-Series models had a great feeling of solidity and strength. There continued to be a sense of prestige attached to the Volvo name, but perhaps with a largely different clientele.

From 1973 the 140-Series was assembled locally. This helped keep the cars keenly priced in an era of very high industry protection.

In August 1974 Volvo introduced its 240 range with the claim that these were the world’s ‘first series production safety cars’. Three years earlier the company had made great marketing capital out of its Volvo Experimental Safety Car (VESC). The Volvo marketing people presented the 240-Series as an all-new model, which was certainly overstating the case. Yes, it incorporated numerous worthy improvements derived from the VESC experience. Yes, it had rack and pinion steering, a new front suspension, and completely new dashboard. And, yes, it had a new nose, stretched for greater crash protection space and finished off with a snout reminiscent of a 1963 Toyota Corona and very similar to that of the VESC. But, no, this was no all-new Volvo.

While many prospective buyers would have been rightly impressed with its capacity to perform as well in a 40 mile per hour concrete barrier test as most other cars did at 30, others would have been put off by the appearance and performance levels more typical of the mid to late 1960s.

It is though entirely understandable – if, with hindsight, misguided – how Volvo management had decided its priorities. This is where economies of scale begin to enter the equation. Volvo was a relatively small company and the expense incurred in developing a collection of 10 safety vehicles doubtless meant that there just wasn’t the money available to give the 240 a new body. This would have been seen principally as a cosmetic exercise. As far as the Volvo product planners were concerned the 140-Series was functionally close to perfect in its packaging – Henry Ford and his Model T, anyone? So from the A-pillar backwards the new car was pretty much the same as the old one. Reinforcing the financial constraints faced by the company is the fact that in 1977 Volvo very nearly merged with the other Swedish automotive manufacturer, rival Saab.

Many people probably couldn’t pick the differences when the 240-Series eventually went on sale locally in 1975.

Consider what was happening in the international automotive industry between 1962 and 1974. Let’s compare Volvo with a manufacturer perhaps slightly below it in pricing and prestige and one slightly above it. In Australia in 1962, perhaps the closest competitor to the newly arrived Volvo B18 was that other newcomer, the (then) fully imported Peugeot 404. The Volvo was faster, plusher and better built, but a little less poised dynamically. Another competitor for the B18 in Europe was the sparkling BMW 1500, yet to arrive in Australia.

Now let’s fast forward to April 1967 when the 140-Series was introduced locally. Does the timing ring a bell? The Ford XR Falcon GT hit the market and instantly set a new performance benchmark among even vaguely affordable cars. The new Volvo was barely faster than its 1962 predecessor and far less sexy. The Peugeot 404 had been much improved from a brilliant starting point. The BMW 1500 had become the 2000TI by 1966.

Now we come to 1975, the year when the supposedly all-new 240-Series Volvos were introduced in Australia. The heyday of series production racing was already over with the XY GTHO having been the fastest four-door sedan in the world four years earlier. The Peugeot 404 had been superseded by the 504, which by 1975 was available in fuel-injected Ti guise. The BMW 528i was a seriously fast and desirable car, albeit with somewhat dodgy oversteer-prone handling. Seriously, how could a car enthusiast opt for a four-cylinder Volvo over any of these?

The engine (B21) itself was redesigned to include an alloy cylinder head with a single belt-driven overhead camshaft. Most of its extra performance was taken up by the extra weight of the safer new car, but it was certainly smoother and happier to rev than its overhead valve predecessor, the B20.

Volvo, of course, was not entirely reliant on four-cylinder vehicles. Its 164 and 164E had impressed with their performance in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But the heavy 3.0-litre straight six was to be replaced with a new, more modern 2.7-litre V6 in the new cars. The Volvo 264 was the first new model to receive the ‘Douvrin’ engine built in France as a joint venture between Renault, Peugeot and Volvo. Lighter, more compact and smoother though this new engine was, it delivered just 140 brake horsepower at 6000rpm, compared with 175 at 5800.

Volvo introduced a new V6 engine with less capacity and a lot less horsepower than the old 3.0-litre straight six. Go figure!

There was never any question that the 264 would not match the performance of its predecessor, a remarkable development in itself, when progress implies gains not losses! Nobody at Volvo seemed worried. New engine, less power: who cares? In its November 1974 edition, Wheels magazine carried a news story on the 244 and 264 newcomers. Even the heading and sub-heading of this report suggest Volvo’s loss of prestige among enthusiasts: ‘Volvo Fights Back’ is the heading, followed by ‘Volvos have been stodgy and crude.’ And the good news? ‘But for 1975 two new engines, including the long awaited Volvo-Renault-Peugeot V6, new suspension and new steering, plus a totally oriented front end styling job…’

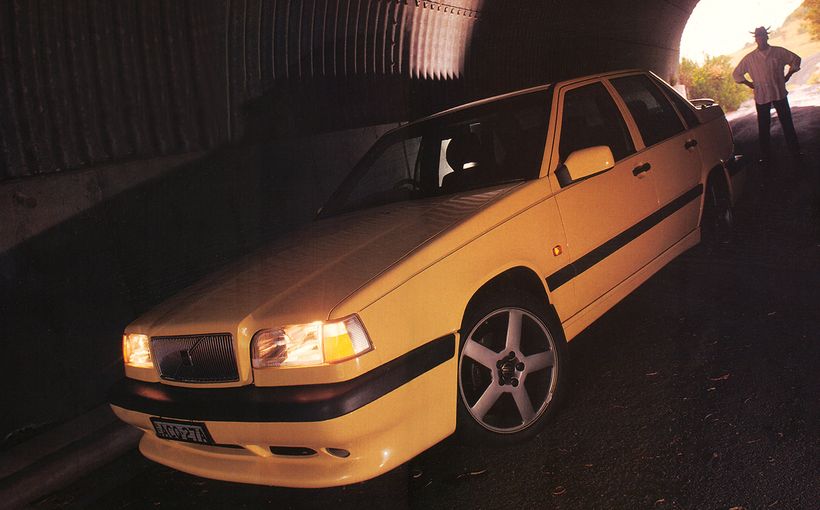

A flattering colour, and perhaps the best angle.

Deeper into the story, we find this gem, comparing the 264 with its predecessor:

Volvo’s attitude to this drop in maximum speed and acceleration is to say so what? It makes the point that the vast majority of its sales are in Sweden, the USA and Britain, where you can’t drive legally at over 110km/h anyhow, and often at rather less. Who cares if the top speed is 177km/h, 169 or – as we suspect – closer to 161km/h when you can’t use it anyway. The Volvo buyer would find this kind of logic difficult to refute, even if he wanted to.

Here is a big part of Volvo’s problem due in part, I believe to its somewhat isolationist position, way up in Sweden. No German manufacturer would ever have fronted the media with such an argument. By 1974 there were BMW sedans that could hit 220km/h. In Australia, by the end of the 1960s enthusiasts were accustomed to hotshot European fours – Fiat 125, Renault 16TS, etc – that could touch 161 under faintly favourable conditions. (On the issue of isolationism: I was astonished in 1998 to discover how far off the pace the all-new S80 luxury sedan was when I attended the international launch. It was if the Volvo engineers were somehow unfamiliar with the pacesetters, namely Mercedes-Benz and BMW.)

Sales of the 264 were not strong and for some months after its launch you could save about $3K and buy the old 164 instead – more performance, less equipment, old-fashioned looks and a lower level of safety.

For Australian Volvo customers main interest centred on the four-cylinder cars. The entry level car was the 242DL (two-series, four cylinders, two doors) with carburettors, four-speed manual gearbox, priced at $6190 in May 1975. Maximum power was just 97 brake horsepower and it is worth remembering that the Holden 149 ‘red’ engine made 100 back in 1963.

All other four-cylinder variants had the fuel-injected B21 2.1-litre engine and 123 horsepower. The front seats were height adjustable which was an unusual and most welcome feature in the era of the HJ Kingswood with park, sorry, bench front seat. The 244GL cost $7395 in manual form and an extra $300 with the three-speed auto. ‘GL’ over ‘DL’ meant 5.5-inch rims with 185/70 rubber over 5s with 175/70s, tachometer, boot and bonnet lights, chrome wheeltrims, carpet in the boot, metallic paint and leather trim. The very popular 265GL wagons were about $200 dearer than the sedan and were also available with a choice of transmission. As for the underpowered 264GL, it was a seemingly absurd $11,725, whether you chose the manual or automatic transmission.

The wagons quickly became fashionable in the more prosperous suburbs, beloved by mothers desiring maximum safety for their children. I stood on a Paddington (Sydney) footpath one day in 1983 to monitor seat-belt wearing and found that the highest proportion of unbuckled drivers were in 240-Series Volvos, doubtless under the impression that the car itself was so safe, no seat-belt was required.

The story did improve as the 240-Series’ long life continued. Even at the European launch in January 1973, Volvo insisted it was more conscious of dynamics. The rack and pinion steering was the biggest single improvement and the 240 got a new MacPherson strut front suspension instead of the old coil and wishbone arrangement. In Volvo terminology, the new car had received a ‘radical redesign of the front suspension and steering to give improved roadholding and handling.’ Even so, in 1979 the 240 received Volvo’s ‘Dynamic Safety’ package which included gas dampers, bigger anti-roll bars, and other improvements, which had been developed for the 242GT, which was introduced that year. According to Wheels: ‘if you own a five-year-old car you won’t believe the difference.’

The reality is that despite the hype at the launch of the 240, the dynamic improvement was less than came later with the 1979 upgrade. Steve Cropley, in his July 1975 Wheels road test wrote:

It’s amazing, after all the work that has been done redesigning the suspensions and geometry of the Volvo, that it feels so much like the old one.

As for the 242GT, to which credit for the ‘Dynamic Safety’ upgrade goes, it was the undoubted highlight of the local 240-260 range of Volvos. It got the 2.3-litre B23 injected engine with 10:1 compression and 140 horsepower. Here was the first overtly sporty Volvo since the P1800 and continues to be one of the very few locally delivered 1970s Volvo to appeal to collectors. At the other spectrum perhaps was the Bertone-designed 262, a lavishly specified V6 coupe with dramatically lowered roofline (a-la Rover P5B Coupè), which prompted various wags to ask owners, ‘who sat on your car?’ About 100 of the total of 6,622 came to Australia, some 200 were sold in Sweden, and three-quarters of them went to the US, where doubtless they looked more at home.

There was great change between 1962 and 1975, meaning the 240-260 were already old-fashioned in styling. But who could have predicted that the four-cylinder models would linger on the local market until the arrival of the front-drive 850 in late 1992? By this stage they had lived beyond the joke stage to become something of an institution. Perhaps one advantage was that remarkably few cars of this size still used rear-wheel drive in 1992.

Throughout its very long life, the 240-Series benefitted from many upgrades. In 1980 the topline 264GL picked up an ‘E’ to become the 264GLE with central locking and four US-style headlights. The next year saw the 242GT’s 2.3-litre four-cylinder engine standardised for all injected 240-Series variants. In 1984 a four-speed automatic replaced the old unit. The difference between a 2.3-litre four-speed auto 1984 model and its predecessor was marked.

Finally, another sporty Volvo, but the 242GT came rather late in the day. David McKay’s decision to race one of these cars at Bathurst on road tyres neither endeared him to other competitors nor added value to the brand through enthusiasts’ eyes.

At this time the 2.1-litre engine was discontinued and there was a new version of the 2.3 with reduced frictional losses.

In 1986 the bonnet was raked more steeply with a lower grille, changes which went some way to giving the 240-Series a more contemporary appearance: it certainly looked better!

The Volvo 240-Series hid beneath its inelegant bodywork extremely high levels of safety but in other respects the car offered few improvements over its 1967 predecessor. It then had to compete in international markets for more than another decade and a half. During this time a wider range of affordable European models came on stream and the Honda Accord drove quietly into this market sector. Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Audi broadened their model mix. Months before the Volvo 850 replaced the 240 locally, Lexus was also competing with the ES300. So Volvo faced a tougher marketing challenge than it had in the 1970s. Amazingly, between 1975 and late 1992 the 240 had faced three generations of BMW’s 5 Series! Excellent as it was – or became – in many respects, the 240 gradually became the butt of more jokes than any other car of its era. Volvo is still recovering from this negative impact.

For Volvo, discretion was the better part of velour.