LX Torana and A9X: from mediocre to meteoric in 18 months

Few cars in history have ever been designed to accommodate four-cylinder, six-cylinder and V8 engines, but the LH Torana was intended to be almost all things to almost all people. Originally conceived as a less expensive alternative to the Kingswood/Premier, costs blew out along with weight and it came to market barely cheaper. For some reason, GM-H management had forgotten former General Motors supremo Alfred P. Sloan, Jr’s dictum that a small car cost almost as much to build as a big one.

With its wide range of powertrain choices and two different bodies, the LH Torana was intended to be even bigger news than it was. That’s because only the sedans were ready for launch in 1974.

Two years down the road, in February 1976 GM-H launched its LX Torana range, the highlight of which was the new Hatchback. The sedans were barely changed.

All LXs got a column-mounted stalk for headlight flash and dipping. The soft-feel steering wheel rim was welcome. Seat upholstery was new and plusher. Clever use of chrome on the waistline and blacked-out window surrounds made the LX look lower than its predecessor.

The highlight was unquestionably the Hatchback. Apart from the stillborn Leyland Force 7, this was Australia’s first offering of the increasingly fashionable configuration pioneered in Europe by Renault with its 16 in 1965, which was voted European Car of the Year the following year.

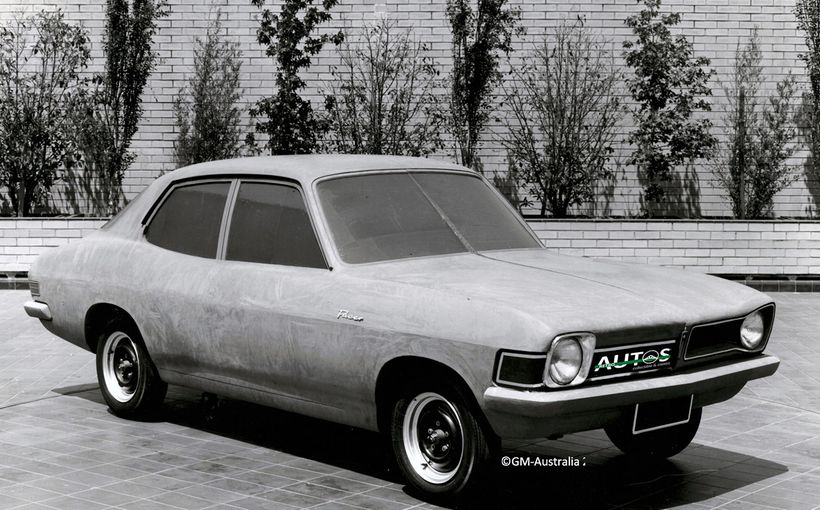

In many ways the Torana Hatchback was a brilliant concept, as stylish as the Renault was, er, awkward. From the A-pillar back it was a completely new car and its design reflected the Chevrolet Monza, while also referencing the brilliant Fiat 850 Coupe.

The news story in the April 1976 edition of Wheels was mostly positive, even if the driving experience came in for criticism common in tests of many Holdens of the pre-Radial Tuned Suspension (RTS) era. Then editor Peter Robinson reckoned it should have been called the HB Torana rather than another LX:

GMH’s stylists have managed to produce a totally professional two-door out of the sedan. The balance of glass to body, the sloping roofline, the slight kick-up of the tail and the impression of a lower waist line are all the work of men who understand styling. The cockpit area owes something to the American Chevy Monza and the new Opel Manta Coupe, both of which have very similar B-pillars to the new Torana. Perhaps the only disappointment is the lack of HB identity at the nose, which is pure sedan.

The front doors were 250 mm longer than the sedan’s but, unlike the Monaro’s they retained the window frame. The hatchback itself had gas-filled struts and was a huge piece. But that elegant line – almost a straight one from where the roof began to slope down to that slight Kamm-like kicked-up tail – entailed one major compromise: the luggage area was almost unbelievably shallow. Certainly, there was more space beneath the floor housing the spare wheel. But bulkier objects needed to be placed close to the backs of the front seats if the hatch was to be closed completely. Irritatingly, the key needed to be used to open it. There was a split rear seat. But when the seat backs were folded forward there was a space between them and the front seats. Headroom in the rear was tight.

An ingenious Hatch Hutch option – of which surprisingly few were sold at what was then a considerable $65 – was intended in some way to compensate for the lack of a wagon or fashionable panel van variant; it is just s-o mid-1970s, in much the same way as the orange stripes!

Just two variants were offered, the SL and SS, both with the 3.3-litre six and four-speed manual gearbox as standard. Either could be optioned with the 4.2-litre or 5.0-litre V8. Blessedly, no four-cylinder variant was on offer. In a way the SL specification foreshadowed the HZ Kingswood SL with reclining bucket seats, carpet and pushbutton radio. So the sparse equipment level of most entry level Holden models was addressed. The SS added a sports steering wheel, full instrumentation, twin exhausts, stripery and a front air dam.

With the 5.0-litre V8 and manual transmission, the SS ran the standing 400 metres in 15.6 seconds. The braking performance, however, did not match the urge. It was all too easy under emergency braking to find the car going sideways. In some respects, this braking deficiency reveals the true story of the early LX Torana and also the HJ/HX Kingswood/Premier.

When the LX Torana range was launched in February 1976, GM-H had begun a major re-engineering program, which the marketing people called Radial Tuned Suspension (RTS): an evocative acronym indeed and one pioneered by Pontiac a couple of year previously. There was less defensiveness in the air. That day, former racing driver Jim Sullivan experienced a quite different response to that usually given to members of the press who criticised Holden handling.

By then, Joe Whitesell had come out from Germany to be Holden’s new chief engineer. Not only did Whitesell listen and respond positively to Sullivan’s criticism, the pair became friends. Months earlier Peter Wherrett had criticised the HJ Holden’s braking performance on his television program Torque. That was when chief engineer George Roberts was still in the job. When the LX was launched, Whitesell had been in the role less than two months. Sullivan got his message through, where Wherrett had been politely ignored.

It was not by chance that the driving-focused American, Whitesell, had been appointed chief engineer. During 1975 a decision had been taken to introduce radical change at Holden. Late that year, Charles S. (‘Chuck’) Chapman, was promoted from being chief engineer at Opel to managing director of GM-H. Chapman brought Whitesell, who had been his offsider, out from Opel a few months later.

Both men were keen drivers. Interestingly, it was during his pre-release drive of the LX Hatchback that Chuck Chapman began to ring the changes. Belting these slick looking fastbacks around Lang Lang Proving Ground he realised that the handing was deplorable. Chapman was used to cars that turned when you turned the steering wheel, cars that didn’t want to go straight ahead all the time, cars that offered a feel for the road: he engineered ’em that way. He liked a smooth ride, but not one that came at the expense of responsive handling.

The forthcoming Hatchback ads would promise sun, surf and the generally trendy life, but who was going to want to understeer their way to paradise?

So Chapman issued a directive along the lines of ‘Sort out this goddam front end so that the goddam car will go around goddam corners!’

Within eighteen months of the LX launch, the entire range of cars from Gemini through to Statesman Caprice had undergone major suspension changes (RTS) and the braking system criticised by Wherrett, Sullivan and others was fixed.

In 1975 though, those engineers who took exception to the directives they received from their boss, George Roberts, could not get their criticisms heeded. The Torque program must have looked like a great opportunity for change. Doubtless many of the engineers had hoped that Peter Wherrett’s opinion would influence Roberts.

No question, the ventilated front disc brakes which were optional across the range and standard on the most upmarket HQ/HJ variants were brilliant. The problem, said Wherrett, was at the rear where the pressure-limiting valve did not prevent the wheels from locking prematurely and sending the car sideways.

Before we get to the RTS revolution, let’s hear Wherrett’s side of the story.

So they flew me down to Melbourne and I went out to Lang Lang. I did the braking test over and over again and every time the rear brakes locked up and the car slewed sideways and we finished up agreeing to disagree. It was all very amicable. George Roberts kindly offered to drive me to the airport. When we got there, I couldn’t help myself. I turned to him and said, ‘George, I now know why your cars don’t handle. George, you are the worst driver I’ve ever been with.’

Internal questioning of George Roberts extreme leaning towards a boulevard ride at the expense of handling began with the HQ launch. When I was doing the research for my 1998 official history of Holden, Heart of the Lion, John Bagshaw, who was sales and marketing manager in the late 1960s and1970s, and later returned from Vauxhall to become managing director, told me:

After that [the HQ launch], we set up a system whereby there were ride evaluation programs. But up until then…you never got a team together to drive and evaluate forward product. Never.

Other executives of the era, including Leo Pruneau and Peter Nankervis, confirmed this.

Mumblings and discontent may have been rife within senior ranks of GM-H, but George Roberts was the boss of Holden dynamics. His experience in Detroit with Buicks and Cadillacs gave him his template. No question, the HQ had a beautifully composed, quiet ride with extreme levels of compliance. But it also suffered from plough understeer. So did the LH and (early) LX Torana.

In 1968 Marc McInnes, an engineer and former rally driver, wrote George Roberts’ speeches. Thirty years on, he was still prepared to argue the case:

The car gave very, very early advice of pending difficulties in control. In terms of pure safety, you could argue that this was a fine example of advising a car’s limits to the driver. The front tyres would squeal long before the car was anywhere near its cornering limit. Let’s not bury George Roberts without giving him some credit for what he was attempting to do in the customer’s interest. The fact that enthusiasts hated it doesn’t mean he was absolutely wrong.

In 1972, McInnes moved to Sydney to run the public affairs office for New South Wales and Queensland. ‘I used to fit sports suspension on all my test cars, and this was much better accepted.’

During Roberts’ last months in the job, Alex Cunningham, General Motors’ director of international operations, visited the proving ground to sample various Holdens. One executive, who did not want to be named, told me:

After the ride and handling session he pulled everyone into the Lang Lang conference room and in front of everyone said to the marketing manager, John Bagshaw, ‘Bags, you must be a bloody genius to sell that shit. And we’re going to do something about it.’ That absolutely floored everyone who was there. It was obvious that the standards which had been set for us were obviously not worldwide best. Very shortly after that George had gone.

Weirdly, Roberts was sent to Opel as chief engineer as Joe Whitesell’s replacement; the wheels of the automotive world move in curious (sometimes understeering!) ways. In the February 1978 edition of Modern Motor, columnist Harold (‘Dev’) Dvoretsky wrote of the latest Opels:

The ride has suddenly become boulevard. They roll. They don’t point as well. They’ve been softened up…It could be just coincidental, of course, but I can’t help pointing out that the current Opel chief engineer is George Roberts…Draw your own conclusions.

Meanwhile, back at Fishermans Bend, young engineer Ray Borrett played a hands-on role in developing RTS, the first recipient of which would be the four-cylinder LX Torana 1900 to be renamed Sunbird.

When Whitesell first came out, he told the engineers that they ought to start work on the suspensions. So they would go out to the proving ground and do their work. They got me involved in evaluating what they were doing. I was just your average shitkicker project engineer, the lowest level that they had and I’d been with the company less than a year. But I just drove the cars and told them what I thought.

A few months later they transferred me from the proving ground up into the chassis design area and I took over responsibility for the Torana and the Gemini suspension development – both design and development at that stage.

I started work on that and then Hanenberger [much later to be Holden’s managing director]came out. He was just a project engineer but he was an expert in handling. He’d worked in the chassis group at Opel for all his working life and had gone through all this process before.

I had a Torana down at Phillip Island. I took every bit of rubber out of the suspension, cut down the control arms, welded plates on and screwed rose joint on. We went through this exercise, just me doing it and a couple of mechanics. We would put a rubber bush in, with no other rubber in the suspension and see what effect it had, then take it out and put another bit in and see what effect that had. It was all seat of the pants.

Then we came up with ‘this bush here affects this characteristic of the car and that bush there affects this other characteristic’. It took a few days.

Thus was Radial Tuned Suspension born. Joe Whitesell defined it succinctly:

Neutral handling behaviour, higher cornering force capability, reduced body roll, steering with high response and an optimum road feedback on-centre feel, maximum straight ahead stability, lack of fishtailing, optimisation of tyre traction, stiffer but no less comfortable ride, smooth ride even under full load conditions.

The first LX Torana – indeed the first Holden – with RTS was the four-cylinder variant, now with a bright new name, Sunbird (replacing the old Torana 1900, a dog that never had its day!). This was in November 1976 and the sixes and V8s would take another three months. As well as the radically improved dynamics, the Sunbird got improved trim and equipment levels.

Ray Borrett’s last job before taking up a new assignment in the US proved to be the finest car GM-H had yet produced. This was the A9X, slipped surreptitiously onto the market in August 1977 raring to race in the Bathurst 1000.

I took an L34 and the first A9X prototype – if you like – and did all the geometry, bushes, steering rack location and all that sort of stuff. I got it running, drove it for two days at the proving ground, made a few changes to it, then hopped on the plane and went to the States. But I left the basic specification for the car behind.

‘A9X’ itself was just one of a long list of model codes available exclusively to GM-H, which got A-prefixes while Chevrolet got Zs – hence Z28. The ‘Performance Equipment Package’ had Bathurst written all over it in invisible ink.

Despite being nominally an LX, the A9X was really a hybrid LX/UC. Here was the first Holden with four-wheel disc brakes. The UC-style floorpan was used in order to fit GM-H’s new Salisbury axle and rear discs under the Torana. Just like the UC, the A9X had its steering gear mounted directly to the chassis.

Being a post-ADR27A offering, the A9X had to use the cleaner but less powerful L31 engine rather than the ‘dirty’ L34. But because the older unit was already homologated, Bathurst-bound A9Xs got the L34. A big improvement came from the Davis Craig thermatic fan.

Perhaps the sole jarring touch was that absurd foot-operated parking brake fitted to all LH and LX Toranas, so that three adults could sit on the bench seat of a fleet issue variant – and how often did that happen?

It is now almost impossible to contemplate what a revelation the A9X was. Compare it, for example, with two different Holdens. The original LH Torana 1900 with its ratbag engine and soggy suspension shared little more than the body with an A9X sedan. The HJ Caprice had a pleasant 308 V8 but its plough understeer was as different from the A9X’s sharp turn-in and outstanding balance as you could get in two cars branded Holden.

Coincidentally, the A9X was created right at the time when Porsche hoped to convince its customers that front engine/rear drive was the way of its future. It was only a question of time before the 928S entirely supplanted the 911. History now suggests that the LX Torana A9X was perhaps the closest car to a contemporaneous Porsche that Australia has ever had, our very own 928S.

Comments