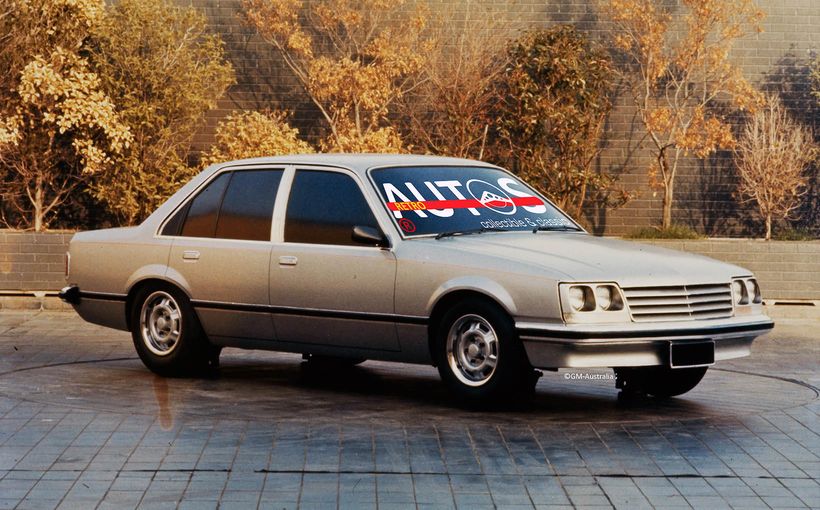

Holden VC Commodore: from feeble Four to HDT hero

Any student of Australian automotive culture wishing to understand the late 1970s and very early 1980s will learn more from the VC Commodore than any other single car. Outwardly, the VC constituted one of the most minor facelifts in Holden history, but strenuous engineering work had taken place beneath that unchanged bonnet.

To understand the VC in context, it’s necessary to revisit the first ever Holden Commodore, the VB which was introduced on 26 October 1978. The VC superseded it just 17 months later. The GM-H product planners had hedged their bets on the Commodore by keeping the Kingswood/Premier and Torana – hard to see why anyone would choose a Torana instead of the similarly sized and only slightly dearer Commodore! – in production until they could gauge market acceptance of their new Opel-derived offering.

In some respects the timing of the VB launch could hardly have been worse. Within months of the car’s release came the fuel crisis. The value of V8-engined cars plummeted seemingly overnight. At GM-H and Ford Australia, product planners and engineers wrestled with different ways of extracting better fuel economy from what were essentially outdated six-cylinder engines. Ford was quicker off the mark with its Honda-supplied alloy cylinder head. But Holden's plans changed to include a four-cylinder engine in the product mix.

In hindsight, this constituted something of an unintended gift to Ford Australia, whose clever marketing executives had insisted that the Commodore was a C-class car, not a D, like their Falcon. The real rival for the Commodore is not the Falcon but the Cortina, they argued. By introducing a four-cylinder version – and a remarkably lacklustre one at that –Holden seemed to support this view.

For the first time since the arrival of the EH in August 1963, the mainstream 3.3-litre six-cylinder engine got a major makeover. In truth, all the work that went into this program did not result in anything like a state of the art six, such as those produced by BMW, but amounted to little more than catch-up. Frankly it’s remarkable that GM-H could have got away for so long with an engine conceived for the 1960s.

If anything, the 202 cubic inch version of this engine was never as smooth as the 186 and 179 units that preceded it. And when it got lumbered with all that ADR27A anti-pollution gear, more refinement was lost. Holden’s greatest single mistake with the VB Commodore was bringing it to market with such an uncharismatic engine.

Hindsight also tells us that the so-called ‘Blue’ (as opposed to the previous ‘Red’) six represented too little too late. While it doubtless helped the Commodore to maintain its number one sales position, the writing was on the wall for the narrow-bodied models –VB, VC, VH, VK and VL; by the mid-1980s GM-H was facing bankruptcy.

The XT5 3.3-litre six made 83 kW at 4000 rpm, up from the previous unit’s almost embarrassingly modest 66 at 3600. Torque climbed from 221 Nm at 2100 rpm to 231 at 2400. Changes included a new cylinder head with larger valves, a new camshaft to flatten the torque curve, a twin-barrel carburettor, new inlet and exhaust manifolds, electronic ignition and a new crankshaft conceived to make the engine much smoother. The result was an engine that was noticeably smoother and which revved more freely.

Nevertheless, the Commodore remained only average in its performance and fuel economy. Wheels editor, Peter Robinson, waxed eloquent in singing the VC’s praises but the figures stood in contrast to his celebratory writing, for a manual 3.3 took 18.2 seconds for the standing 400 metres, the same time as a 1968 1.6-litre four-cylinder Fiat 125.

In response to the downturn in the popularity of V8s, Holden made this upgraded six-cylinder engine standard in the premium SL/E, which had previously come with the 4.2-litre V8. With its automatic transmission the SL/E took 19 seconds for this benchmark test.

And how about the fuel economy? It was somewhat better but still short of impressive. Driven for economy on the magazine’s dedicated ‘fuel loop’, the manual car got 24.6 mpg and the SL/E just 20.7. By contrast, over the same 83-kilometre loop, a 4.1-litre Alloy Head XD Fairmont Ghia (automatic) managed 24.8. Through the 400 metres its time of 18.3 seconds put the Ford significantly ahead of the Commodore SL/E. So the so-called XD1/2 had much better performance than its Commodore rival and significantly better economy. You’d have to give the sixpack engine victory to the team from Broadmeadows. (Of course, Holden still had its 4.2-litre V8.) It’s a pity Ford Australia’s efforts to extract better economy from its larger and more powerful six-cylinder engine received only faint praise in the influential Wheels magazine.

Certainly, the VC 3.3 was a step ahead of the previous car but its economy still fell below the desired level. Probably the greatest gain was felt by buyers of wagons who regularly carried a load. Because the new engine spread what power and torque it did possess over a more generous rpm range, its superiority over the old red unit would have been obvious in this context. The wagon itself remained a thing of some joy, living up to that old axiom ‘car-like’ in its driving characteristics.

Despite all Holden’s cleverly reasoned arguments about the capacity of its Commodore wagon to accept a bigger box than its Falcon rival, many fleet buyers remained unconvinced. During the period of its smaller-bodied Commodores (1978-1988) Holden surrendered a large part of its fleet share to Ford Australia. And Ford Australia had always been more zealous in pursuing this important sector of the market: typically in the last quarter of the twentieth century more than 60 per cent of Falcon sales went to fleets. (It is also interesting to note that during the EA to EL period some 58 per cent of all new Falcons were fitted with towbars!)

But Holden had a second arrow in its quiver. Some genius decided that the answer to poor fuel economy was to introduce a four-cylinder variant. Ford Australia briefly considered this idea for the Falcon but wisely dropped it. Enter the Commodore Four. Cheekily (and after having waxed eloquent on the ‘blue’ six), Wheels listed its road test on the contents page of the September 1980 edition as: ‘Fourtifying the Commodore: is it a better Sunbird?’ It was a fair question.

Tester Mike McCarthy pointed out that the four was barely cheaper than a comparable six. The entry level 2.85-litre Commodore L cost $7658 and the four undercut it by just $255. Move up to mid-range SL spec and the price difference was $682 ($8429 to $9111) but this time the sixpack was the 3.3-litre unit. McCarthy put it well when he wrote: ‘Price is the Commodore's first hurdle’ (referring to the SL four which was the subject of the test).

The somewhat laughable ‘Starfire’ engine name had been dropped in favour of ‘Phase II’. It was much quieter, smoother, but sadly even less powerful with just 58 kW at 4600 rpm instead of 60 at 4800.

The lighter Four got 13-inch wheels instead of the bigger-engined cars’ 14s (15s for SL/E) and lost its rear anti-roll bar.

It cost more than rivals like the Corona (and Cortina) but was slower and thirstier. But it had easily the best dynamics in the sector, which probably helped to justify the higher price. There were not all that many customers though.

The kindest way to encapsulate the VC Commodore Four is to describe it as a great car in search of a better engine. Its standing 400 metres time was 20 seconds flat which puts it on a par with the 1962 Fiat 1500.

Infuriatingly, the throttle positioned device fitted to manual models to reduce emissions stopped the engine from returning to idle for six very long seconds.

These days the Commodore Four is surely a desirable model for collectors (though less so than any other variant) but in 1980 it failed to hit the spot with buyers and was discontinued with the launch of the VK in 1984.

Other changes from VB to VC included tweaks to the suspension to reduce body roll and a different feel to the brake pedal aimed at pleasing average drivers rather than racers or would-be racers. It was still definitely the driver’s car of the then Big Three, although the XD was probably not as bad as Wheels said. (I owned a VB Commodore 4.2 when I went to work at Ford Australia as the Graduate Training Co-ordinator. I did many kilometres in topline XD variants and rated them highly. The finish was also much better.)

The exterior changes for VC were minimal with the most obvious being the neater eggcrate-style grille. The cover of the January 1981 edition of Wheels showed this new nose to its maximum advantage. The car was a red one with red, black and white stripes and obviously wider wheels beneath flared guards. This was, of course, the first ever HDT model. ‘Flat out in the HDT Commodore’ said the cover line.

Without doubt, historians will always be more interested in Peter Brock’s first production car than they will be in the Commodore Four. It was the absolute highlight of the VC's 19-month run.

The HDT Commodore was based on the SL/E which meant air-conditioning, power steering, velour trim, four-wheel disc brakes, headlight wash/wipe and much more. In addition, it received the 333 option pack which included dual exhausts, central locking, and fast glass.

Then the boys at HDT got to work. The body got a plastic air dam, rear bootlid spoiler and wheel arches plus striping in Marlboro colours (it was the Marlboro Holden Dealer Team, after all) and gorgeous 7-inch Irmscher Alloy wheels all the way from Germany. A four-spoke black leather Momo steering wheel with Brock’s signature and a faux wood gearshift knob distinguished the cabin. Very welcome was the rest for the left foot.

Better brakes, Bilstein lowered suspension and much engine work to the venerable 5.0-litre V8 were other key ingredients. You can argue about the value for money of the Commodore Four but $19K for the HDT was astonishing, considering it was simply the fastest four-door sedan on the local market at the time with its standing 400 metres time of 15.5 seconds and top speed of almost 215 km/h.

One interesting innovation was the new Shadow Tone paintwork, very highly desired nowadays by Commodore collectors. If you couldn’t stretch your 1981 budget all the way to an HDT, then an SL/E 5.0-litre four-on-the-floor and dark green over light green would have been a pretty good alternative. I’d love one now.

The availability of the Shadow Tone paintwork on the SL/E by itself makes the VC more desirable than its VB predecessor but the introduction of the revised 3.3-litre six-cylinder engine and the fabulous HDT Commodore were the real highlights. This was a very good car in 1980 with some brilliant qualities but it was beginning to lose the sales race against the XD Falcon which was a much better car than the press, especially Wheels magazine in the formidable personage of editor, Peter Robinson, judged it to be.