HOLDEN 48-215 AND FJ: Best in the World…for Australia

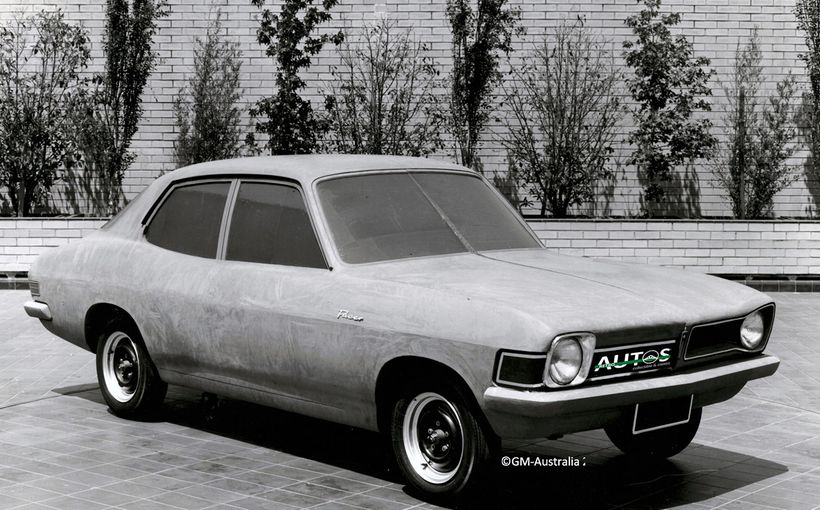

Even when it was new the original ‘Humpy’ Holden 48-215 (‘FX’) disguised its breakthrough engineering behind an essentially pre-World War II appearance. ‘Australia’s Own Car’ was designed, engineered and tested in Detroit before being tested again in Australia. You couldn’t even call it a Baby Boomer because work on 195Y25, as the program was unevocatively called, had begun before hostilities ended.

The 48-215 was always better than it looked. Behind its creation lies a veritable jigsaw of pieces, and foremost among these is its chief engineer, American, Russell S. (‘Russ’) Begg.

While the chief engineer of the Holden was not exactly a performance car freak, he certainly decided that his car should have a better power to weight ratio than just about any other sedan of its era. Russ Begg already had white hair when he was appointed to the Australian car project in 1944. He had graduated with an engineering degree from the University of Michigan 35 years earlier but had always been a progressive, even radical thinker.

Begg had to push his ideas for what kind of car 195Y25 should be through the General Motors engineering hierarchy. No way, when GM president and chairman, Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., approved the Australian subsidiary’s submission to get its own car, was he or anyone else conceiving a vehicle that would match a Chevrolet on performance. In fact, what GMH boss Lawrence (‘Larry’) Hartnett envisaged was a basic four-cylinder economy car. They, we, got much more than that!

One day in Detroit in 1946 Begg and two other engineers went for a drive in the Opel Kapitän. Begg had engineered this luxury sedan during the Third Reich. The Kapitän had been introduced late in 1938 and with the intervention of World War Two there had been little development time during the seven years since its debut. So it was still pretty much state of the art, quite a rival to Mercedes-Benz.

Between 1934 and 1939, Russell Begg, the radical thinker, had transformed Opel’s range of cars by introducing monocoque construction, first on the four-cylinder Olympia and later on this six-cylinder sedan. He was a pioneer in this technology. Opel sales rose exponentially with the brilliant new range of cars. From being merely number one in Europe, Opel enjoyed an immense sales advantage over all rivals by the time Hitler invaded Poland.

Before joining General Motors in 1934, he had worked at Budd, the company which pioneered all-steel bodies in an era when most cars still used timber in body on frame construction.

From Budd Begg went to prestigious Stutz. When the Great Depression claimed Stutz as yet another victim, he went to the General and was sent to its German subsidiary, Opel. Hitler had just become Chancellor, and even then was bent on total war in Europe.

Monocoque (or unitary) construction was still rare and Citroën’s evocative Traction Avant made its debut less than two years before the Olympia (named for the 1936 Berlin Olympics where African-American Jesse Owen ran to glory, embarrassing Hitler and his fellow Nazis).

Hitler’s first major political act as Chancellor was to remove all sales tax on new cars. He knew that to wage total war he needed a vibrant industry which could be converted quickly to produce aircraft and armaments. For Russ Begg and General Motors, this provided the perfect impetus to make the huge investment necessary to create a new range of Opels using monocoque construction.

Unitary bodies were at once lighter and stronger. This meant you could replace an old model with a lighter same-size car which would perform better and use less fuel, or develop a physically bigger and better equipped car that would weigh the same as its predecessor.

The Kapitän was the first General Motors car to combine a six-cylinder engine and monocoque construction which makes it a true predecessor to the Holden. But, unlike the Holden, the Kapitän was not conceived as a low-priced popular model. In its case the power to weight advantage conferred by unitary construction was offset against additional vehicle size and more equipment rather than as a means of reducing weight and fuel consumption. The Kapitän was Opel’s way of taking a tilt at Daimler-Benz. It was obvious that much of its new technology would be used in other GM cars as soon as possible.

Remarkably, the car the Kapitän replaced had been introduced a mere 18 or so months earlier (telling us much about the pace of change at Opel under the Americans). This was the body-on-frame Super Six. The Kapitän weighed just 13kg more despite being 250mm longer. But the Super Six was very close in size to the 48-215 and provides another piece in our 48-215 puzzle.

The prevailing assumption at the time among those working on the Australian car project (195Y25) was that it would be a less powerful machine than the Opel Kapitän which had been bred for high speed cruising on the new German autobahns. It certainly wasn’t going to be as grand and the decision had only recently been taken to use a six-cylinder engine rather than a four.

It was not surprising that Begg would take his work on the Kapitän as one of the main influences on the Holden. Some Aussie engineers had been sent to the US to work with Begg and one of them, George Quarry, had accompanied Begg on this jaunt.

Quarry wrote to the managing director of General Motors-Holden’s, Laurence (‘Larry’) Hartnett:

"Russ, Kuip and I were out in the 2 ½ litre Kapitan [sic.] sedan which, while weighing 2676 lbs. curb, with a 150.9 cubic motor on a 106.1" wheelbase, has very similar internal space and performance factor as our job (actually 90.3 compared with our 90.1). I told Russ that I felt that Australia would have accepted a somewhat reduced performance factor, especially if it had a beneficial effect on weight and cost; his reply was that such a move is quite in the other direction, as any substantially lower performance factor means a different and heavier transmission to handle the greatly increased second gear work."

Note those words ‘quite the other direction’. Conventional wisdom in 1946 was to link low cost and low performance. If you want to keep weight down, you also keep engine size and output low so as to impose lower stresses. Certainly General Motors Overseas Operations (GMOO) chief engineer, Walter Appel, thought along those lines, having expressed ‘considerable doubts about Begg’s high stress-low weight approach’ (in the phrasing of Australian engineer, Bill Abbott). Abbott also noted at about this time that Begg was an ‘absolute stickler’ on minimising weight.

Here was the moment in the 195Y25 when Begg began to push hard for the formula that would be unique to the Holden until it was challenged first by another General Motors product, the Vauxhall Velox, and then by Ford’s Zephyr.

ou can almost see the penny drop. It’s as if Begg stepped out of the Kapitän and decided: ‘I can have this size engine in a much lighter car for a brilliant power to weight ratio, great acceleration and top speed with astonishing fuel economy.’ There was also the Experimental Light Car 195-Y-15 (and its otherwise identical four-cylinder twin, 195-Y-13) developed by Begg in Detroit shortly after returning to the US from Germany). It was discarded as insufficiently robust for manufacture, whether as a smaller Chevrolet or an Opel or Vauxhall. But it did provide a starting point and it’s easy to see that 195-Y-15 led to 195Y25. Interestingly, the 195-Y cars were similar in size to the Opel Super Six. (I wrote my PhD thesis on how the Holden came to be so brilliant, and how its excellence grew out of the Sloan-created GM culture, dating from the 1920s.)

And that was the formula that set the Holden apart from all other cars in the world in the late 1940s: low weight, biggish engine with abundant lowdown torque, simple three-speed gearbox. Begg added nine inches of ground clearances at the insistence of Australian engineer, Jack Rawnsley. For the Australia of the early postwar years there was no choice between the city and the bush, it was Sydney and the Bush. Unlike most other first world countries, Australia had little bitumen and most of it was in the city and suburbs. Even the Hume Highway between Sydney and Melbourne was not fully sealed.

As well as being unsealed in long sections, the Hume Highway was undivided, which brings me to another strong point of the Holden: acceleration. At the time of its launch and for the first couple of years of production (with demand running years ahead of capacity), the top-selling car in Australia was the Austin A40. Imagine trying to overtake a semi-trailer in one of those! People liked it well enough but it was far from ideal.

For many Australians an A40 was their first ever new car. Smaller and less spacious than the Holden, it was also markedly inferior in performance. At home in narrow English lanes and pretty rural villages, in country Australia with its huge distances between towns (let along capital cities), appalling roads and sometimes very high temperatures, it was comparatively out of its depth. The Austin A40, as it were, couldn’t speak Australian. With its 1.2-litre four-cylinder engine it needed more than 20 seconds to reach 80km/h, which was its highest practical (noisy) cruising speed. But the Holden reached 80 in 13 seconds, could cruise all day at 60-65 (around 100km/h) and climbed hills (accelerating) in top where the Austin battled in the third of its three ratios.

Trading up from an A40 to a 48-215 represented a major leap forwards. Interestingly, in early planning towards the proposal for an Australian car, Larry Hartnett wanted a car ‘somewhere between the two types’ of English and American. ‘Mr Hartnett,’ recorded the minutes of a meeting held in his office on 20 December 1943, ‘was of the opinion that the present day US automobile was a bit too grandiose for Australia’s actual needs, and, on the other hand, European cars were a little bit too much the other way. Perhaps a solution to the problem would be a car somewhere between the two types…Desirable features in an Australian made car included 30 miles per gallon performance, light weight and comfort for long distance driving…’

Not only was the 48-215 a car between two types it was also a car between two eras. Based on a 1938 prototype and developed in the mid 1940s, it took the most advanced mass-production automotive thinking forward into the 1950s.

There would be a long wait for the next model, which the public expected to be all-new. That car was the FE which would not appear until July 1956. The biggest news with the 1953 FJ facelift was the availability of the Elasco-Fabulous Special, even though early FJ Specials used tough leather upholstery rather than the much vaunted Elascofab vinyl with two-tone colour schemes and elaborate buttons.

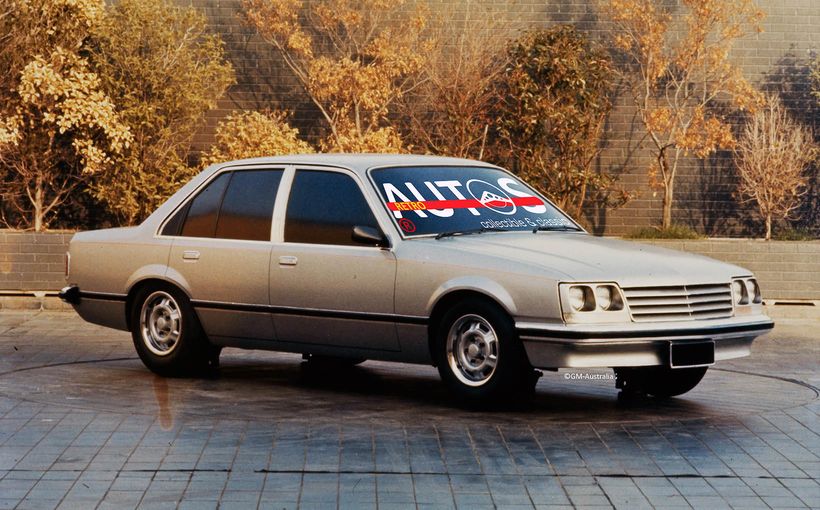

The FJ with its scale model tail fins and garish new grille represented a nod to Detroit. But it didn’t seem like sufficient change. It was almost an anti-climax with thousands of 48-215s colouring Australia’s road in uniquely local colours such as Convey Grey, Gawler Cream, Mortlake, Flinders Blue and Trentham Green. Already the new Vauxhall Velox (which drew so much engineering inspiration from Russ Begg’s work), first shown in late 1951, looked more contemporary with its faired-in guards and copious chrome. And then there was the Ford Zephyr, which had actually started life as a planned smaller Chevrolet (the Cadet) before its engineer, Earl MacPherson (yes, that MacPherson, with the distinctive spelling) decamped to Ford. The Zephyr dated the 48-215 overnight, two years before the FJ hit the streets.

It is a little known fact that the GM stylist given the Australian car project was Frank Hershey whose next job would be to make a big contribution to the 1948 Cadillac and who, after moving from GM to Ford, was the man who shaped the ’55 Thunderbird. Hershey described the Holden as a ‘cute little car’, as if to say, barely worth remembering. Hershey styled the Holden in limbo land, before new ideas had got a grip on the design studios, just before GM styling guru, Harley Earl himself had decided on the new directions of postwar styling.

So the Holden got warmed-over pre-war themes, emboldened by a particularly striking grille. At least it looked more modern than the 1948 Chevrolet which was little more than a reheated ’42 model with a horizontally disposed frontal treatment.

Larry Hartnett would have been happy enough with this approach because he had always wanted an unassuming type of car, but by the time the Holden was launched Hartnett had been shown the door in favour of American, Harold Bettle.

Even though exhaustive testing took place in Michigan and in the roads around Melbourne prior to the launch of the 48-215, there were still minor durability issues and steady running changes were made, most notably the suspension upgrade in March 1953 with the introduction of telescopic shock absorbers along with wider springs.

At the time of its launch the Holden was the only car in the world that could achieve 30 miles per gallon, reach a top speed of 80 miles per hour, seat five adults with good space for luggage, and offer nine inches of ground clearance. It is not going too far to say that it was the best car in the world for Australian conditions, truly Australia’s Own Car! It was certainly vastly superior to anything from Austin, Morris, Ford, or even Vauxhall, and vastly less expensive than anything from the US. Truly a unique niche vehicle.

Although the FJ model continued the sales momentum, the Holden was beginning to show its age as new rivals displayed more modern priorities – wider, lower bodies with a more streamlined three-box look. Its engineering was still the equal of any modestly priced car with the arguable exception of the Redex Trial-winning Peugeot 203. Just how advanced the 48-215 was in 1948 is revealed in this chart. Check out the brake horsepower to weight ratios to see how far ahead of its time the 48-215 really was.

Check out the brake horsepower to weight ratios to see how far ahead of its time the 48-215 really was.

As for the FJ its lasting contribution to Australian automotive culture was the world of street machining before that term was even coined. The undoubted star of the 2005 Australian International Motor Show was Holden’s tribute to the FJ, EFIJY.

In conclusion, only General Motors had the international expertise – and especially that of Russell S. Begg – to give Australia what was truly and outstandingly its Own Car. The FJ consolidated the great start made by the 48-215 and has lodged itself as one of the icons of Australian culture.