Hillman Imp: the daring little car that ruined Rootes

As a car-crazed boy the Rootes Group used to strike me as a weird name for an automotive corporation, perhaps the more so because its cars seemed mostly humdrum. For me, the word 'Hillman' conjured up images of dumpy fawn or grey sedans offering a similar level of excitement to my father's (grey) Austin A30. But something radical happened in 1963 (by which time Dad had traded the A30 on a marvellous cherry red Morris 850, which was always 'the Mini'). That something radical was the Hillman Imp.

When the Imp made its debut, the Rootes Group was on quite a roll, although few could have known that this rear-engined marvel, this extreme piece of automotive design that almost made the Mini-Minor seem like the new orthodoxy, would prove to be the product that clinched Rootes's future, or rather its lack of one.

Heading into the postwar era the Rootes Group was in a stronger position than most British carmakers. Its factories had emerged unscathed from German assault and the budget bottom line for 1945 was a then huge £1.5 million pounds profit. As a reward for their significant contribution to wartime production, first Billy (in 1942) and then Reginald, four years later, were knighted. Sir William knew that all he had to do was to sell 1930s era products for the first couple of years and then create a fresh range of cars, most of which would be exported. It was export or perish with the government insisting that about 70 per cent of all cars made in Britain had to be sold overseas. That's why the Austin A40 Devon popped up in New York showrooms and the Austin A90 Atlantic, the sports car answer to the question no self-respecting American could possibly have asked, was invented.

Apart from being pleasantly cashed up, Sir William had another advantage over his rivals. In 1948 he engaged Raymond Loewy who had signed a contract with Studebaker the previous year, as an advisor on styling. But the Sunbeam Talbot seemed a greater beneficiary of the Loewy influence than, say, the 1949 Hillman Minx. I do remember in 1956 or 1957 being surprised by how American the radical new Minx Series I looked with its low-riding style and reverse rake C-pillar (three years in advance of the 105E Anglia).

For all his undoubted acumen, Sir Billy did miss the automotive opportunity of a lifetime, an opportunity which, had he seized it, would probably have meant that the Hillman Imp wouldn't have been dreamt up, let alone thrown into production. Sir William Rootes headed a government commission which went to the ruined Volkswagen plant in Wolfsburg to see whether Hitler's car could be revived to aid the postwar recovery. Famously, the Rootes Commission concluded that 'the vehicle does not meet the fundamental technical requirements of a motor car…It is too ugly and too noisy…To build the car commercially would be a completely uneconomic enterprise…'

How extraordinary was it then that less than two decades later the Rootes Group's first mini car aped some elements of the Volkswagen? Towards the end of the 1950s it became obvious that the corporation needed a car to rival the Morris Minor, Austin A30/A35, Standard Eight/Ten and Ford Anglia/Prefect. And, maybe, the Volkswagen itself?

As is so often the case the impetus for such a project came mainly from the drive of one determined individual. For the Rootes Group this was Peter Ware, who was appointed as chief engineer, Ware was an enthusiast, unlike his predecessor, B.B. Winter. Somewhat amazingly, Ware was successful in getting the Apex program for a small rear-engined car approved. It seems that he did this in spite of Sir William Rootes's opinions because the chairman of the board refused to ride in the first prototype. That earliest incarnation of an idea, known (perhaps retrospectively) as the Slug, had an air-cooled engine and it is reported that not only did the Rootes family knock it back but Sir William himself refused to drive or ride in it.

While historian Graham Robson documents the history of Rootes in compelling fashion (Cars of the Rootes Group), he doesn't explain just how it was that Peter Ware overcame Sir Billy's and presumably Sir Reginald's and son Geoffrey's objections to that first prototype. As for Ware's own enthusiasm for the project, that doubtless arose because two young men had impressed him with their ideas.

The design of the new mini car was done by Michael Parkes (1931-1977) and Tim Fry (1935-2004). Fry recalled: 'We were very bored with the sort of cars Rootes were producing and with the arrogance of youth we went to the Technical Director and told him we could design just the car he needed. He just said 'All right, get on with it!' But in 1955 this amounted to no more than a feasibility study. Mike Parkes was later a development engineer at Ferrari. He also raced Ferraris in Formula One. (Asked in 1967 what private cars he ran, the answer was: 'I have a 1,000 cc Rallye Imp and a 1952 manual gearbox Mark VI Bentley'. The Rallye was built only to order and was intended for competition use.) Interestingly, Alec Issigonis, father of the Minor and its Mini-Minor successor, was to quote Mike Parkes's younger brother (by 12 years) John a 'family friend'.

The Apex small car program had its genesis in 1955 but probably gained momentum from the Suez Crisis of 1956-57 which drove BMC into its Issigonis Mini project. Germany was experiencing a bubble car craze. The Rootes Board members were shown two or maybe more prototypes starting in 1957. Apparently, they made it clear that they did not want a minimalist bubble-type design but a proper car, something more substantial than these prototypes. Air-cooling was out. But it seems that the rear engine configuration was established from the beginning.

It was Tim Fry's idea to approach Coventry Climax, whose engine he believed would suit a small car. Kenneth Sharpe, chief development engineer on the project, recalled in 2005 at least four 'short wheelbase' prototypes before 'Mike and Tim shoe-horned the 750cc Climax in place of the air-cooled twin. Inevitably more space was required for the bigger engine and its water cooling system, bigger wheels and larger saloon space'.

Even as I write this story, I find myself wondering why the Apex team was so resolved to make a rear-engined car – given that the concept seems almost cute nowadays! – and then I remember that in the mid-1950s time frame only Citroën had a small front-drive car in production, even if at least one other manufacturer, Renault, was hatching (pun unintended but appropriate) a plan. As for 'family friend' Issigonis, he would have been unlikely to share his Mini vision with rival designers. If there was such a thing as 'orthodoxy' in mid-1950s small car design it was front engine/rear-drive, while the bolder designs were a-la-Volkswagen: Renault 4CV (followed by the Dauphine) and Fiat 600 (then the Nuova 500). And small car design did not subdivide itself into mini-car design – aside from the bubble cars – before the Nuova 500 and the BMC Mini (whose maker effectively coined the term).

When it comes to the Hillman Imp, hindsight spells out a recipe for disaster. It was Rootes's first car of this size, its first with a rear engine. Then, as Graham Robson stresses, it was to be built in an all-new factory in Scotland by novice workers. Well, what could possibly go wrong? Then there was the timing. The Imp, scheduled for late 1962, would not actually arrive until mid-1963 by which time BMC's world-beater had been on sale for the better part of four years.

As for the name, thereby lies a tale involving a Humber Super Snipe, the car at the opposite end of Rootes's odd spectrum. Ailsa Craig made marine engines and one of these in the interregnum between World Wars was called the Imp. In 1962 the company was acquired by another and all its assets were up for sale. Rootes acquired the Imp name in exchange for a Humber Super Snipe. Truly stranger than fiction.

Researching this story I gained a new insight. It may have been a mistake that the test drivers used in the development program were all skilled. Garrett ('Garry') Walker writes:

At the end of the pre-production tests I was sent over to the US to work on another product, but I was there with the introduction of the Imp to the US market. It wasn't the right car for the market, but John Panks, Chief of Rootes Inc. certainly did everything to promote it. An Imp crossed the US coast to coast in just over 42 hours. A plan to drive from Miami to Fairbanks (5000 miles in five days) only just failed. The rear suspension collapsed within 200 miles of the finish line. Suitably customised 'Lord' and 'Lady' Imps were featured at the New York motor show.

Customer complaints and service problems included insufficient heat and transmission failures when driven on long thruway journeys. This was apparently caused by the differential pumping the oil away from a bearing when driving at steady speeds…as found on thruways. Price was a factor. A new Mustang was only $300 or so more.

I know other problems arose after the introduction.

In retrospect I think the type of people chosen to drive the test cars should have been different. We were all young enthusiasts and good drivers and I think that unconsciously we adapted our style to the capabilities and needs of the cars, without even knowing it. We didn't ride clutches, we raised engine revs when changing down, we didn't let the engines slog, etc, etc. We watched out for understeer on slippery surfaces and took great care in strong crosswinds! Somewhere early in the testing program more cars should have been given to truly lousy drivers who would have found their weaknesses far quicker than we did. At one point a car was lent to a lady who parked it facing down a really steep slope. (In the same circumstances I think we would have found a level patch.) As with me, the fuel ran out of the filler cap.

In all the overseas tests we didn't have an accident. We were spotted in northern Sweden by some enthusiasts, and someone got into our garage in Cortina and took some photos which gave me heartburn, but that was all.

The Rootes Board's insistence that the new baby Hillman should not be a cheap, no frills economy car allowed Mike Parkes and Tim Fry to choose the overhead camshaft aluminium alloy engine. At the time of launch the Imp was the only car in the world with an all-alloy engine – not bad for a tiny car! There was an aluminium gearbox case. The engine was originally 750cc but almost every component was changed and the production Imp had an 875cc unit producing 39 brake horsepower. It is no overstatement to say that this was still a racing engine, albeit fitted to a somewhat heavier machine.

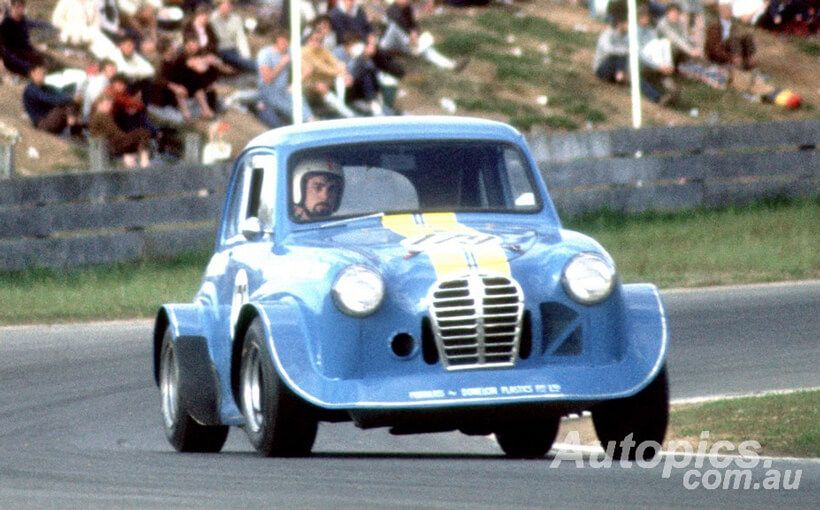

There was never any doubting the Imp's credentials as a driver's car. One tester remembered that every Imp driver seemed to be smiling in the action photographs; there was often a front wheel off the ground. The most surprising aspect of the Imp's appeal is that it was a Rootes car. With the honourable exceptions of the Alpine and Tiger sports cars, most of these were utterly conventional and dull to drive. While utterly different in its road manners from the Mini, the Imp was every bit its equal when it came to delivering driver joy. The engine was canted 45 degrees to keep the centre of gravity low. After testing a Chevrolet Corvair (from which, incidentally, the Imp's styling inspiration was derived), the designers insisted on semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension to minimise oversteer. They even chose swing axle geometry for the front end. So the Imp is one of those likeable cars that displays both oversteer and understeer and puts the driver at the centre of the action: so, a great car for keen drivers but not so good for uninterested motorists.

Of more practical consideration was the opening rear window which pre-dated the hatchback. The rear seat folded down to yield a generous luggage area. And there was synchromesh on all four gears (unlike the Mini). Third and fourth were tallish ratios. The shift was joy on a stick. The Imp had an automatic choke and gauges for temperature, voltage and oil pressure.

A Mark II with improved front suspension geometry, better trim, manual choke, among other changes was introduced in 1965.

The Imp went on sale in Australia in 1964 but was never more than a minor player. The Imp Californian coupe and the Commer Imp variants were never sold locally but we did get a high performance variant known as the GT ('Hillman GT' without the 'Imp', based on the Singer Chamois Sport). My lasting memory of the GT sadly did not take place in the driver's seat but mainly in the rear view mirror, then speedily overtaking and vanishing into the middle distance. I was in my Fiat 1100 103D on a university night rally – no closed roads in those relatively carefree days – and this Imp, seemingly with nine blazing lights obviously had a driver more talented than its navigator.

Curious that dropping of the Imp badge on the GT. Certainly by then the car had a dubious reputation for reliability, but who could have mistaken the shape?

Rootes was another British automotive manufacturer which specialised in badge-engineering. The luxury version of the Imp sedan was the Singer Chamois and there was a Sunbeam Stiletto coupe, but blessedly no Humber Hummingbird or suchlike.

I have never driven an Imp. Perhaps that's just as well or I would probably have had to buy one, maybe several! In more recent years many enthusiasts have found in this once almost forgotten treasure the ideal cutprice alternative to an old rear-engined Porsche.

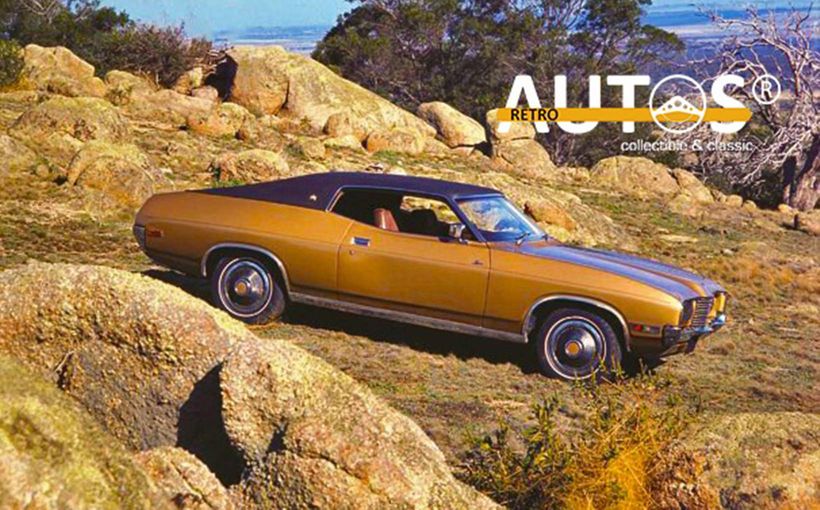

The Imp now seems barely credible. That a company renowned for dull mainstream sedans should have allowed such a car to be put into production beggars belief. And how badly the project was implemented! Rootes management hoped to sell 150,000 per year but the best was about a third of that in heyday 1964. On 4 June of that year Billy (by then Lord) Rootes sold a large stake of his corporation to Chrysler. In 1967 Chrysler completed its takeover. Amazingly, the Imp soldiered on until 1976.

In summary, the Hillman Imp is one of those rare mainstream models that represents the triumph of the automotive imagination over corporate constraint.