Datsun Z Cars: Japan’s GT redefines the breed

As is so often the case, the original version is the cleanest.

The Datsun 240Z was the car that put the Japanese automotive industry on the international stage. Not only was the ‘Z’ greater than the sum of its total parts, it was greater, too, than the sum of its assorted inspirations. It was a true original, which amounted to nothing less than the re-invention of the sports car.

At the time of its first public showing, on 18 October 1969 at the Tokyo Motor Show, popular thinking still clung to the notion that sports cars were distinct from coupes, that the open air component was an intrinsic element (and lurking not far behind that view was the associated assumption that perhaps a sports cars should also be a little bit uncomfortable). But the more far-sighted observers could already make out the writing on the walls of the US safety legislators. In the land where MGs and Austin-Healeys and, indeed, Nissan’s own Fairlady, commanded strong sales, within a handful of years open-topped cars would virtually disappear. Even the relentlessly indigenous products of Detroit such as the Cadillac Eldorado convertible and the four-door Lincoln Continental convertible were set to join the dinosaurs.

In the 1960s, if one thought about the MGB or the Jaguar E-Type, one pictured first the convertible version and then the coupe variant – in the case of the ‘Bee’, the GT. Nissan, of course, already had its Fairlady, an old-style sports car in the idiom of the MGB or Austin-Healey but superior in almost every measurable way, especially by the time it was offered with a 2.0-litre engine. It made great sense, then, for the next dedicated sports model to be produced as a coupe, even though there were some product planners within Nissan who questioned the logic of this approach, believing that an open car would be less expensive to manufacture. But this was not the case because the coupe could be conceived as a one-piece (monocoque) design, dispensing both with the separate chassis and the need to brace that chassis to minimise the inevitable torsional flexing.

It was not until near the end of 1968 that the final decision was taken to produce the original Z-Car as a two-seater coupe. The scribblers enjoying hospitality on the Nissan stand on 18 October 1969 saw immediately how the new coupe fitted into the Datsun product range. The new car was called the Fairlady Z, emphasising its close relation to the open top roadster. Both used a 2.0-litre straight six-cylinder engine.

The first Fairlady had made its debut in January 1960. While this small roadster paid tribute to British ideals – even taking its name from the Lerner and Lowe musical – the would-be Miss Doolittle of sports cars was intended to compete on the US market against the established British brands. Katsuji Kawamata-san, the president of Nissan, saw My Fair Lady on Broadway.

But even the excellence of the 2000 paled in comparison with the Fairlady Z. Indeed, Yutaka Katayama-san, who was Nissan’s chief executive in the US, suggested dropping the genteel name because it belied the new coupe’s aggressive character.

There can be no question that the 240Z benefitted from great timing. It was conceived just as the United States was moving inexorably towards a new era of safety consciousness in the wake of Ralph Nader’s 1965 book, Unsafe at any Speed: the designed-in dangers of the American automobile. And it was produced when the Japanese automotive industry was superbly placed in terms of economies of scale, efficiency of operation and international currency exchange rates.

The single most obvious influence on the design of the 240Z is the Jaguar E-Type. But, the Datsun could be said to have trumped the Jaguar’s ace. When the E made its debut at Earls Court in 1961, few understood how Jaguar could have produced such a car for the price, half or even a third of natural rivals.

Fast-forward to the end of the same decade and the coming of the Z-Car. Although not quite as fast or plush as the famous Jaguar, the new Datsun was comparable. The E-Type, like so many other British cars of the era, had not progressed enormously from the time of its introduction to the end of the 1960s. Its handling was by no means exemplary. Fuel consumption was heavy. And the Jag’s ergonomics were quaintly English and outmoded. The E-Type’s pricing relationship with its British and Italian competitors was barely changed since 1961, but when the Z-Car hit the streets, suddenly and for the first time the classic Jaguar no longer looked like bargain high-performance motoring. In Australia, the Datsun was a little more than half the price of an ‘E’.

In the 1965-68 gestation phase, Nissan benchmarked several existing champions, among them the E-Type, the MGB, Alfa Romeo Spider, the Healey 3000, Triumph TR, Porsche 911 and, less predictably, the bespoke Facel-Vega Facellia. There was also plenty of Nissan heritage to be folded into the formula.

The superb Toyota 2000GT was designed after the car that was the basis of the 240Z.

Albrecht Goertz, who had worked with Raymond Loewy on the 1950-53 Studebakers, then shaped the gorgeous BMW 507 and was at Porsche when the 911 (initially 901) was being done, was engaged as a consultant by Nissan in May 1963. When, in 1965, Goertz moved to Toyota and developed the 2000GT, he had already done a prototype for Nissan called A550X which contained many styling themes of the 240Z.

Toyota may not have sold many 2000GTs but the company gained fabulous publicity for itself in particular and the blossoming Japanese automotive industry in general. This spurred Nissan to move its Goertz prototype forward towards mass production.

There can be no doubt that the driving force behind this decision came from Yutaka Katayama-san, who wanted to move the company upmarket in the US. Katayama believed there was no future in selling low-priced cars forever into this huge market. At the time he was also doubtless conscious of the enormous enthusiasm with which American customers had embraced the Ford Mustang. But Katayama envisaged a unique sporting model not spun off any existing sedan. He also believed that the sports car should be affordable in a way that, say, an E-Type Jaguar (let alone a Ferrari) was not and to this extent he probably saw the chief rivals as being British models such as the MGB which was hugely successful in the US. Nissan’s US boss was, however, convinced that the new car should have a closed roof. Besides, Nissan already had the Fairlady 2000 convertible. And so the Nissan board swung its collective weight behind perhaps the most exciting new project ever undertaken by the Japanese automotive industry.

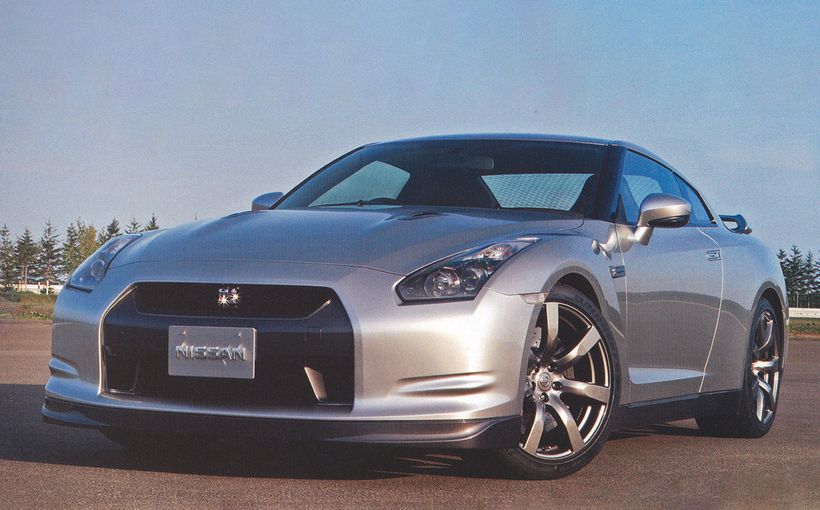

Yoshihiko Matsuo was appointed chief designer of Nissan’s Sports Car section. He began work on the new concept in November 1965. He was just 31 years old but his experience on the Bluebird SSS was seen as a big advantage. Indeed, it was Matsuo who coined the term Triple S, from Super Sports Sedan. The SSS serves as another reminder that Nissan’s credentials in the sporting market were the strongest in Japan. They had been further served by the amalgamation with Prince in August 1966, a long-term liaison which led to the creation of the Nissan GT-R.

The pricing of the 240Z was the final proof of the international competitiveness of the Japanese industry, particularly Nissan.

From its inception the Z was destined to be radical. Firstly, it would be a dedicated new sports car not based on any existing vehicle. Secondly, it would sell in a lower price range than its ostensible rivals. Thirdly, it would be conceived especially for the US market with a view to giving Nissan greater prestige. With its advanced overhead camshaft six-cylinder engine, it offered more urge than the four-cylinder Alfa Romeos. Unlike the Mustang, or indeed the Australian Holden Monaro, it was not based on a sedan platform. Rather, the 240Z offered some 90 per cent of the performance of a Jaguar E-Type and 90 per cent of its sex appeal, for little more than half the price in the US. In its first road test of the Datsun 240Z published in April 1970, Road & Track had concluded:

we expect to see the Datsun establish a market of its own, one which will force other makers to come up with entirely new models to gain a share in it. The Japanese industry is no longer borrowing anything from other nations. In fact, a great struggle may be ahead just to prevent a complete reversal of that cliché.

Not that the testers had found the car perfect. The ride was choppy and the steering was too susceptible to front-end adjustments. But styling, interior comfort and appointments, performance, handling and braking were all rated highly. Car & Driver observed in its June 1970 edition:

Datsun didn’t invent the overhead-cam engine, or disc brakes, or independent suspension, but it has a habit of incorporating these sophisticated systems into brilliantly conceived and easily affordable cars. That is why the 240Z was so much more than the sum of its parts.

Most other magazines around the world drew similar conclusions to Car & Driver. In Australia, the 240Z quickly became known by insiders as the 24Ounce. We got the five-speed gearbox as standard (while US customers got the four-speed). There was an auto option.

The interior of the 240Z was truly charismatic as well as ergonomically sound. Compared with contemporaries such as the Holden Monaro, it was more like a traditional English sports car but closer to a Jaguar E-Type than an MGB.

At Nissan, road tests were pored over and improvements were made to the 240Z to meet most of the writers’ concerns. Unfortunately for purists, the company’s eventual response was the softer, heavier 280ZX.

Some testers compared the 240Z’s performance with a Porsche 911S or Ferrari Dino 246 GT, the acceleration time from zero to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) being within half a second. Invariably, the Datsun delivered superior acceleration and a higher top speed than all other sports cars anywhere close to its price range – no surprise when you considered it came with a 150 brake horsepower (112 kW) six-cylinder engine and weighed little more than most four-cylinder rivals with 100 horsepower (75 kW) or less.

Nissan’s straight six is an engine of great character.

As for the new 2.4-litre engine, it was based on the brilliant single overhead camshaft 1.6-litre four used in the Datsun 1600, the model which cleared the bitumen for the arrival of the fabulous 240Z.

When the Z-Car was ready for its first significant upgrade, a 2 + 2 variant was added to the range. The differences in design are not all down to practicality, but reflect the fact that the two cars were done by different designers. (In turn, this explains why sometimes the design of the original 240Z is credited to Akio Yoshida rather than Yoshihiko Matsuo. But Matsuo was the chief designer and Yoshida was his assistant. It was Yoshida though who had done the work on the 2 + 2 prototype which never came to production during the life of the 240Z.)

The 240Z was not merely successful, it quickly became the world’s best selling sports car.

In the manner of Porsche, Nissan chose to make running changes to its cars. The June 1971 edition of Wheels magazine detailed 14 minor changes that had been made to the car since the Australian launch in October 1970. Revisions in September 1973 included a de-tuning of the engine to meet new emission laws.

While the really big news brought by the 260Z was the new 2 + 2 variant, extra low-speed torque which came with the larger engine would be welcomed by customers who still wanted the two-seater.

The additional capacity was achieved by lengthening the cylinder stroke (up from 73.9 mm to 79). But the new engine was less sporting in character, despite a slight gain in performance. A characteristic of longer stroke engines is less willingness to rev.

In its April 1971 road test of the original Z, Modern Motor recorded a zero to 60 mph time of 10.0 seconds and a top speed of 119 achieved in fourth. The heavier 260Z 2 + 2 (Modern Motor, September 1974) managed 10.8 seconds and 118 respectively.

After considerable internal debate, one imagines, in 1974 work began on what was effectively a redefinition of the Z as fully fledged GT, still with many of the features of the older models but with a new emphasis on luxury and refinement. It would use the engine already on offer in the US in the 280Z but the body would provide more room for occupants and superior comfort, with greater attention to detail.

The body, despite its similarity, was all-new and almost 40 mm wider. It was also slightly lighter, thanks in part to the extensive use of plastics. But this new coupe was much stronger and surpassed itself in Nissan’s extensive crash-testing program. Safety was as much part of this new design as was sportiness or luxury. Past that first blush of similarity to its already famous predecessors, significant change was evident. Importantly, the ZX achieved an excellent-for-1978 CD figure of 0.385 (Audi’s 0.30 being still three years into future tense, and unpredictable!) compared with 0.467 for its predecessor. A reduction in aerodynamic drag means lower noise levels and improved fuel economy. In the Z’s case it also meant a sleeker look with that long nose pushing smoothly forward in a steady curve to an integrated front bumper. Already the radiator grille had been consigned to history. The generous stretch of the bonnet also allowed the engine to be moved aft in the interests of superior weight distribution, close to 50:50. This stretch applied to the rear as well where increased overhang accommodated an 80-litre fuel tank, extra luggage, and allowed for a more stylish response to US safety legislation as it applied to the rear bumper. The second generation Z constituted a seamless new streamline, ready for the 1980s and gesturing towards the following century.

The 280ZX was better proportioned in terms of the relationship between wheelbase and overall length. You notice this especially in the two-seater which was never made available in Australia. Its wheelbase was stretched by 15 mm, which not only provided extra space but accentuated the improvement to the ride which resulted from numerous subtle suspension changes. Conversely, the 280ZX 2 + 2 lost 85 mm in the wheelbase to achieve a tighter turning circle.

The Z had consistently put on weight since 1969 and by the mid-1970s some customers craved power steering. Nissan made this desirable feature standard on the 2 + 2 with the added benefit of reducing turns lock to lock from 3.5 to 2.7, giving the car a welcome responsiveness at the wheel. An excellent air-conditioning system was also fitted on 2 + 2 models.

A deeper glasshouse made for an airier cabin and enhanced the lower, more purposeful demeanour of the ZX. Great attention was paid to colour combinations and two-tone colour schemes were available. The B-pillar was thicker in the interests of greater body strength and was finished in chrome.

Fundamentally, the 2.8-litre straight six derived from the 2.6 and 2.4-litre versions which preceded it. But where the 2.6 was a ‘stroked’ version of the smallest unit, the 2.8 had a larger bore. Nissan chose a less complicated version of Bosch’s L-Jetronic fuel injection system than that found in Mercedes V8s. This enabled the 280ZX to meet all legislative requirements while retaining similar performance to the original 240Z with much improved driveability and similar fuel economy (despite all the added weight).

From 1980 T-bar removable ‘semi-transparent’ roof panels were introduced as a new option that brought even more versatility to the Z. It seems likely that this brilliant move was inspired by the phenomenal success of the 1976 Pontiac black and gold Special Edition Trans Am and to a lesser extent the gold Special Edition Grand Prix of the same year, both of which were conceived to celebrate Pontiac’s half century. (Interestingly, Pontiac used a Hurst T-top through until 1978 when the change was made to a design by General Motors’ Fisher Division.) The 1968 Corvette was the first American car to use the Hurst T-top.

In order to make the T-bar concept viable, the engineers reinforced the roof. These targa panels worked beautifully – easy to remove and stow, their absence made no difference to the stiffness of the car, thereby eliminating a major disadvantage of the full convertible style of body. I owned a light blue and silver 280ZX for some months and loved this feature. In its press release of 5 February 1980, Nissan Australia suggested the arrangement provided the ‘advantages of a convertible while retaining luxury car comfort.’ The 280ZX was almost the complete all-rounder.

It has been a commonplace of criticism that the second generation sports car lacked the hard edge of the earlier models, particularly the 240Z. What is overlooked here is that in many respects the ZX was superior in its road qualities. Not only did it ride much better, but it had much better brakes – discs all round, ventilated on the front. During my ownership I remember thinking that the model’s success in Group E (production car) racing was at odds with such criticism.

Despite some reservations from those who wanted a more aggressively themed sports car, the 280ZX must be judged a resounding success. It was sold from 1978 to 1984 and during that period 414,628 were produced, taking total Z output past 1,000,000. On 12 September 1983, Nissan Motor Corporation Limited’s International Division published a press release under the heading: ‘Cumulative Production of the Fairlady Series Reaches One Million Units’. This figure included the Fairlady roadsters but by the end of 280ZX production, the Z had notched up six-figure production in its own right. Considering this occurred during one of the most troubled times the automotive industry had ever faced, the achievement now looks all the more remarkable.

In less than a decade Nissan had created a most valuable brand within a brand and arguably Japan’s most famous sports car. It is no wonder that these Z Cars – especially the pioneering 240Z – are now increasing in value.