Austin X6: Jaguar aspirations but six-cylinder 1800 reality

The Austin X6 range probably deserved to sell more strongly than it did. In several respects this uniquely Australian car was ahead of its time. But its sheer differentness from the bland Australian mainstream sixes, poor marketing and quality issues meant the Tasman and Kimberley were destined never to be more than very minor players.

Launched in early 1971, the X6 was unashamedly intended to encourage prospective buyers to associate it with British Leyland’s premium car, the Jaguar XJ6. The entry point was $2598 for the single headlight Tasman manual. Add $290 for automatic transmission. The up-spec Kimberley was $2888 as a manual and $3148 with automatic.

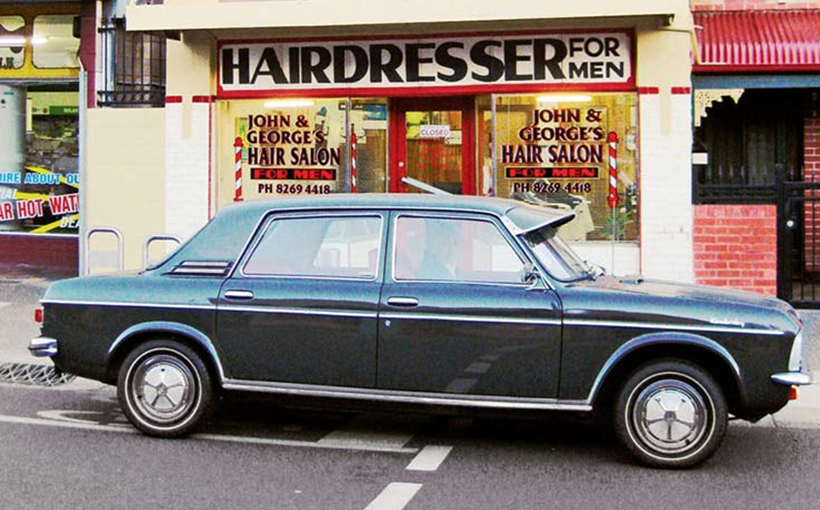

You could distinguish between the Tasman and Kimberley easily because the former had single headlights and a very simple grille, while the latter had quad headlights, a more stylish grille with plenty of chrome, side rubbing strips and more ornate wheeltrims.

Both used a new six-cylinder engine, developed by Australian engineers from the single overhead camshaft four-cylinder unit first seen in the Morris 1500 and Nomad. In what looked like a very 1960s solution to obtaining extra power, twin carburettors were fitted to the Kimberley.

Despite an additional eight inches of length, the X6s had a similar interior package to the Austin 1800 Mark II they superseded and rode on the same fully independent Hydrolastic suspension.

The initial marketing campaign failed: the new car was presented as a direct rival for the Big Three. It seems that the majority of buyers of Holdens , Falcons and Valiants were unlikely to be attracted to a strange looking front-wheel-drive car – remembering that the Morris 1100 and Austin 1800 did not have outstanding reliability records in Australia – and a shortfall of torque at around 2000rpm where Australian drivers customarily expected it.

Nevertheless, the stopwatch proved the X6 to be as quick or quicker than its purported rivals and some tests of the Kimberley recorded top speeds of more than 100 miles per hour.

Less than 18 months after the launch of the X6, the BLMCA (British Leyland Motor Corporation Australia: how clumsy is that?) team had a Mark II version ready. By this stage, the company’s Australian strategy was evident. Wheels editor, Peter Robinson, in his typically insightful way put this very well in a June 1972 edition comparison between the upgraded Tasman, VH Valiant, XA Falcon and HQ Holden:

The Tasman is obviously out of the mainstream of conventional six-cylinder cars but this doesn’t mean it can’t satisfy the same requirements while continuing to hold a strong appeal to the more discerning motorists. It’s not hard to imagine the Kimberley, especially, running a $5000 plus price tag if it carried BMW or Volvo badges and was fully imported.

But it is the complicated engineering which has reacted against Leyland in Australia and forced it to produce the Marina – a car cheap to run and repair but uninspired technically.

Certainly there was a lot to like about the Kimberley. The Mark II version had lost its rather complex twin-carburettor arrangement mainly because of cost and the fact that it only delivered the promised superior performance high in the rev range where few buyers ventured. But the new models boasted cleaner detailing and, it was said – can someone hear a boy crying wolf? – greater reliability.

The Mark II was marketed as car that offered an alternative to the meat and three veg of the rear-drive locals. (The Kimberley did boast some other minor changes in the attempt to compensate for the loss of the pricey twin carburettor configuration, but still couldn’t match the old model for top-end urge.)

By this stage, there were different judgements at hand. British Leyland boss, Lord Stokes, had declared in 1971 that the X6 was not suited to Australia. But the unnamed author of a road test in the August 1972 edition of Modern Motor wrote:

By this stage, there were different judgements at hand. British Leyland boss, Lord Stokes, had declared in 1971 that the X6 was not suited to Australia. But the unnamed author of a road test in the August 1972 edition of Modern Motor wrote:

To say simply that the vehicle is unsuited to the local market is too trite. Leyland themselves admit they made a mistake in the marketing approach to the car. They looked at the Big Three and tried to equate their vehicle to the best sellers…

Leyland have accepted the fact that it is an unusual vehicle and they are after people who value engineering individuality above looks or familiarity.

So, a kind of Australian Citroën perhaps?

By mid-1972 it was public knowledge that the X6 was not long for the new car market. In the test quoted above, we find:

But time is running out for the X6 – it will be withdrawn from the market when the Australian six/V8 [the P76] is released sometime next year. Which is a pity, because the overall concept and execution of the vehicle is good.

Shortly after the Mark II X6s were introduced, I bought a 1970 Camino Gold Austin 1800 Mark II manual, far and away the newest and best car I had ever bought. While I would never have described it as underpowered, I certainly felt it could easily have coped with more urge. Even years later after I had owned a Renault 16TS, an HK Monaro GTS 186S and a Fiat 125, I regarded the 1800 as the best handling car I had driven, with the possible exception of my father’s 1966 Peugeot 404 when re-shod with Michelin XAS radials (and I later bought that car from him).

The Hydrolastic suspension was superb. Point to point, that Austin was seriously quick. There was one favourite stretch of road with a series of corners with 45 mph advisory signs that it effortlessly traversed at a steady 80. The steering was low-geared and heavy at parking speeds but had great feel (even though it suffered from rack rattle). This was absolutely a driver’s car with immense interior room and a lovely airy feel.

I, for one, could never have contemplated owning a Holden Kingswood even with the optional four-on-the-floor gearshift rather than the Austin, but the car I really did covet was a Mark II Kimberley. The price I paid for the 1800, which I bought from a factory dealership, was $1450, reflecting the severe depreciation these cars experienced. There was no way I could rustle up the funds for the new model.

There was an inexpensive Mark I that I drove and could probably have afforded; but I hedged. Here is the interesting part of the story. I went to another yard and drove something else (I can’t remember what kind of car it was). The sales man there said to me, ‘some cars aren’t worth having even if they are free and one of those is the Austin Kimberley’. He said these cars were just rubbish, totally unreliable, badly built, etc.

Now I hadn’t experienced a completely trouble-free run from the 1800, which had done 37,000 miles when I bought it. A clutch slave cylinder fault, leaky suspension boots and other minor irritations plagued the car. I even tracked down the previous owner, who had traded it on a Mazda 1800. So, in the end, I never thought seriously about a Kimberley again, but my view now is that word of mouth from rival sales people more than real problems with the car itself did much of the reputational damage.

There is no question that the 1800, Tasman/Kimberley and the P76 all possessed superior dynamics to other Australian cars. Braking was excellent in an era when that attribute was not to be taken for granted. Front disc brakes were standard and the car was some 150kg lighter than its rivals, on all of which (at the lower levels of the range) front discs were optional. But the up-spec Kimberley, at least, should have been equipped with power steering, an issue that defied the engineers’ considerable efforts.

In the end, the P76 had even less time on the market than the X6 it replaced; Leyland Australia as it eventually became known could not, it seemed, get anything right. But a great part of the failure of both these cars was a lack of public acceptance, due to too much difference or unreliability rumoured to be worse than it actually was.

In theory, the X6 concept seemed inspirational. Mel Nichols wrote a comprehensive story in the February 1971 edition of Wheels, headed ‘Poor Man’s XJ6’ (and the August 1972 Modern Motor test was called ‘Junior Jaguar?’). The opening paragraphs set the tone:

Remember the ‘Mustang-bred’ campaign that Ford used effectively to give its pony car image to its bread-and-butter Falcon?

There was hardly anything more desirable to the masses than a Mustang, and Ford cashed in big on a ready-made and spectacularly successful image.

British Leyland is now following an identical line; ‘From the builders of Rover, Daimler and Jaguar come the brilliant Austin X6s, the Kimberley and Tasman…’

The emphasis is squarely on luxury, performance, safety and quality – a hint of something a cut above the rest – and it’s a wise move for BLMC because the X6 goes into a section of the market where there’s room only for a car with a definite image.

Near the conclusion of the story, Nichols writes:

BLMC has a lot riding on the X6. It’s the beginning of an adventurous new era for the Australian offspring of the British giant, both in engineering and marketing.

When Lord Stokes gave Zetland [BLMCA’s headquarters in south-west Sydney] the ‘All-Australian’ go ahead in 1968, the X6 concept was a quality family car to replace the faithful 1800 but with none of its failings. The new car had to be similar in size and design, but with better styling, more power and a decent boot for starters. And the budget was to be restricted to a low $4.5 million (Ford spent that much just developing its new 250 CID motor).

BLMC was able to save a lot of money by laying down terms of reference, then having B-L in England act as styling contractors. Zetland says this in no way affected the truly-Australian concept of the car and its overall 85 per cent local concept (the gearboxes and a few other parts are still imported).

And with the car (new body, new engine, new suspension, new trim) on the market a little more than two years later, we think BLMC Australia has done a good job.

Once again the ingenuity inherent in the Australian automotive industry was apparent. Something of the lateral thinking that gave us the Austin Freeway and Wolseley 24/80 in 1962 (but taken much further) defines the X6 program. Those 1962 cars got an Australian-developed six-cylinder version of the B-Series four but the styling was barely revised. So the X6 was arguably the most Australian product seen to date from the British firm, although the Morris Major Elite of 1962 was very cleverly conceived.

Good as the X6 was, it was easy even at the time to see how it could have been better. Mel Nichols concluded his test thus:

The car’s finish and attention to detail is good, it has an extremely high safety level, fine handling, braking and comfort with neat, functional styling. The performance will still be a little on the mediocre side for some drivers, but that will be cured with the bigger ’72 model.

Meanwhile, the Kimberley/Tasman are practical Australian family cars at extremely competitive prices, and might just live up to B-L’s mini-XJ6 image…

Peter Robinson’s comments about the hypothetical possibility of a $5K pricetag had the car been produced overseas by BMW or Volvo invites analysis of just why the X6 failed to attract the necessary custom.

The basic design was so good that the flaws remaining became almost overwhelming. For example, the cable gearchange was dreadful – poor on the 1800 and worse on the six-cylinder car. The driving position featured the same bus-like steering wheel angle. And, it now seems to me, Leyland missed the opportunity of positioning the Kimberley more as a luxury sports sedan, a great value six-cylinder alternative to the Fiat 125 and Renault 16TS.

Great as the concept was, it lacked finessing. The product planning was perhaps a little simplistic. After all, the sixpack weighed less than the B-Series four. At the very least, one wonders why a more highly tuned edition of the twin-carb version was not included in the model mix.

In summary, the X6 Tasman/Kimberley – and, in my view, probably especially the original twin-carb Kimberley – will eventually be highly prized by discerning Australian collectors. They were undoubtedly the most interesting English/Australian models ever created.