BMW 3.0 CSL: Moffat, Brock and the Batmobile

Australian touring car legends Allan Moffat and Peter Brock are best remembered as arch rivals in Fords and Holdens in the 1970s. However, during that time they also ventured overseas to prove their skills against the world’s best - and both were behind the wheel of BMW’s legendary 3.0 CSL.

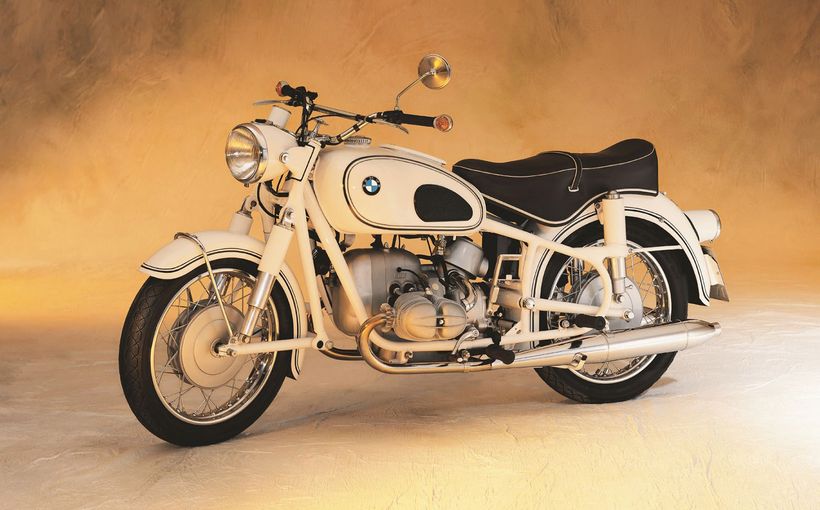

Affectionately known as the ‘Batmobile’ because of its radical bodywork, the 3.0 CSL was the definitive racing version of BMW’s handsome E9 CS six cylinder coupe, which sold alongside its E3 sedan stablemate as the Bavarian car maker’s ‘New Six’ range launched in 1968. However, only the sedans were sold in Australia.

Moffat was first to experience the awesome performance of the 3.0 CSL, after receiving an invitation from the BMW factory team to drive in the 1975 Sebring 12 Hour race. He played a key role in BMW’s prized victory; another less-known but intriguing chapter in Moffat’s career that will be revealed in this story.

Brock’s brush with the 3.0 CSL came the following season, when he spearheaded an Australian-based attack on the Le Mans 24 Hour in 1976. Driving a privately-entered car, Team Brock had to overcome significant budget and logistical challenges.

Unlike Moffat, Brock did not win in his first drive of the Batmobile, but the thinly-funded Aussie outfit earned admiration and respect from European teams for its gallant efforts in a car not expected to have performed as well as it did.

Sadly we never got to see a full-house 3.0 CSL competing in Australia, but its E3 sedan sibling, in both 3.0S and 3.0Si specifications, did prove its sporting prowess in local 3.0 litre touring car racing.

3.0 CSL: A Brief History

The first six cylinder CS (Coupe Sport) was the 2800CS with a 2.8 litre version of the company’s superb M30 SOHC engine. In 1971 it was enlarged to just under 3.0 litres resulting in the more powerful and faster 3.0 CS, before BMW raised the bar again that same year by replacing the carburettors with fuel injection to create the 3.0 CSi.

This sensational grand tourer, with around 200bhp and a top speed approaching 140mph, formed the basis of the 3.0 CSL with the ‘L’ denoting ‘Leicht’ or Light. Its drastic weight loss was crucial to the car’s success in racing, because the big coupe was far from a featherweight in standard trim. It tipped the scales at around 1400kg compared to Ford’s rival RS2600 Capri which weighed less than 1100kg.

Production of the 3.0 CSL commenced in 1971 to gain FIA Group 2 homologation to compete in the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC). However, as a minimum 1000 units had to be produced, the CSL was not approved for racing until 1973.

Central to its weight loss program was a lightweight body-shell made by specialist coachbuilder Karmann from thinner gauge steel with no sound-proofing compounds, along with aluminium doors, bonnet and boot lid, Perspex side windows, lightweight sports seats and deletion of the front bumper bar and all luxury items. This removed about 235kg, resulting in a competitive fighting weight of 1165kg in road trim. Racing versions were even lighter.

The CSL also featured smooth wheel arch extensions to shroud much wider racing wheels and tyres plus a ZF five-speed gearbox.

The arrival of the 3.0 CSL in 1973 was a godsend for BMW teams after they had battled through three seasons with the heavyweight 2800CS which, even with fiberglass panels and other weight-saving measures, weighed over 1200kg.

Despite intensive engine development by factory-supported tuners Alpina and Schnitzer, with multiple carburettors and later Kugelfischer fuel injection, the BMW teams were outgunned by smaller and lighter rivals. These included 1970 ETCC champion Alfa Romeo and in 1971-72 Ford's RS2600 Capris prepared by the company's German racing division in Cologne.

In 1973 BMW fronted with its own official factory team and the new 3.0 CSL, with the fuel-injected M30 engine enlarged to 3003cc. This small increase moved it up to the 3.0 litre division which under the liberal Group 2 rules allowed a capacity increase of up to 3.5 litres. The Cologne Capris were still a match until mid-season, when a BMW homologation upgrade clearly gave the CSL the upper hand.

This included a new crankshaft and 3.5 litre ‘big bore’ engine with around 380bhp. And even wilder aerodynamics developed in a wind tunnel, with the largest front spoiler to date, vertical splitters mounted on the front guards and a full-width scoop across the trailing edge of the roof which directed airflow downwards onto a huge rear wing. In this configuration, it soon earned the nickname ‘Batmobile’.

The new 3.5 litre engine spec and aggressive aerodynamics produced a staggering speed increase, too, with as much as 15 seconds being carved off the CSL’s previous best times at the infamous Nurburgring. BMW left Ford in its wake by winning all of the remaining ETCC races in 1973 and claiming both the driver’s and manufacturer’s championships.

The 1974 ETCC between the 3.0 CSL (now with a 24-valve head and experimental ABS) and Ford’s new 24-valve Cosworth V6-powered RS3100 Capri promised to be the mother of all battles. However, the world’s first oil crisis prompted savage cuts to racing budgets, resulting in BMW contesting only a few ETCC rounds and Ford’s competition department in Cologne closing its doors at the end of the year.

In 1975 BMW ceased production of the CS coupe but the 3.0 CSL’s racing career was far from over. While BMW focused its factory racing efforts on the IMSA GT series in the US (where Moffat enters the story), Alpina and Schnitzer continued the fight in Europe, winning the 1975 ETCC.

In the 1976 ETCC, a revision of the Group 2 rules saw the cars effectively return to 1973 specifications but that had no effect on the 3.0 CSL’s winning ways. The Belgium-based Luigi team won the 1976 championship and more ETCC crowns with different teams followed in 1977, 1978 and 1979 before its Group 2 homologation expired.

Moffat: 1975 Sebring 12 Hour

Ford hero Allan Moffat scored one of the biggest wins of his career on March 25, 1975 when he won the Sebring 12 Hour endurance classic in a works-entered 3.0 CSL.

It was the first time Moffat had raced anything other than a Ford in his professional career and a hugely important victory for BMW, as the Bavarian manufacturer was focused on building a reputation for prestige cars with a unique sporting flavour in its largest export market.

F1 star Ronnie Peterson was originally chosen to share the drive with British international Brian Redman, but when the Swede became a late withdrawal BMW Competitions Director Jochen Neerpasch had to quickly find a replacement. Given the wealth of driving talent available in the US and Europe, the fact that Moffat scored the drive was proof of his international standing.

For the 23rd running of the Sebring 12 Hour, BMW entered a pair of 3.0 CSLs in the GTO division (GT cars Over 2.5 litre) with one crewed by Redman and Moffat and the other shared by German ace Hans Stuck and versatile American Sam Posey.

Sebring International Raceway is a notoriously bumpy and challenging 5.4 mile (8.6km) road racing course on the site of an old WW2 airbase. The annual 12 Hour is an immense challenge for cars and drivers, covering twice the race time and distance of the Bathurst 1000 in Florida’s oppressive heat. The once-around-the-clock race starts mid-morning and finishes late evening.

BMW adopted a classic ‘hare and tortoise’ strategy, with the Stuck/Posey car to be driven flat-out from the start to break the back of the Porsche challenge. If it later retired as expected, the more conservatively driven Redman/Moffat car would be well positioned to win.

Reigning Sebring champs Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood in their Porsche Carrera RSR struck trouble soon after the start, allowing the Stuck/Posey BMW to take the lead and set a blistering pace for six hours before an oil leak led to a blown engine. At that time the Redman/Moffat 3.0 CSL was in second place, inheriting the lead with a three-lap buffer over another Porsche in second place.

Due to the high heat and humidity, the surviving BMW (like all cars) was uncomfortably hot inside and the drivers had been complaining of dehydration, so the team decided to add Stuck and Posey to the roster and regularly rotate the four drivers to keep them fresh and alert during the difficult night stages.

It was a huge victory for BMW against the usually dominant Porsches and what made the champagne taste even sweeter for Moffat, Redman, Stuck and Posey was that they also set new GTO records including average speed (165.183km/h), number of laps completed (238) and total distance covered, which was almost 2,000km.

Moffat more than held his own in such esteemed company, earning him high praise from BMW and international acclaim as one of the sport’s finest sedan drivers. His selection was also a great compliment to Australian motor sport as a whole, with Moffat being presented with a commemorative plaque by the Light Car Club of Australia for his outstanding achievement.

Brock: 1976 Le Mans 24 Hour

Peter Brock always wanted to race overseas. After leaving the Holden Dealer Team in 1974, he had enjoyed remarkable success the following year in a privately-entered Torana L34 owned and prepared by Norm Gown and Bruce Hindhaugh, which included his second of nine Bathurst wins.

For 1976 the plan was to establish his own racing operation - Team Brock – with the hope of attracting factory support for an international program. Late in 1975 Brock got wind of a 3.0 CSL looking for a buyer in South Africa, so he flew to Kyalami to inspect the car following the annual 9-Hour endurance race held there each November.

Brock had a positive meeting with BMW Motorsport staff. A good relationship with the company’s competition department would be crucial to his overseas plans, as it was responsible for providing lucrative factory support in the form of funding, parts and technical information for favoured privateer teams around the world.

Brock was told that the factory would not only assist him in Europe, but given BMW’s desire to strengthen its brand image in the Pacific Basin, his efforts back home in Australia (plus NZ, Macau and South-East Asia) would also receive support. Suitably encouraged, Brock bought the 3.0 CSL. It was considered a good deal as it had never been crashed and came with a huge spare parts inventory.

However, not long after the car was shipped back to Australia and into Team Brock’s humble Melbourne workshop, BMW’s corporate policy changed. The motorsport arm now had to be self-sufficient, which meant no more funding for private teams and all parts and technical assistance now came at a substantial price.

This instantly put the whole Team Brock BMW program in jeopardy. However, having already purchased the car, Brock was left with no choice but to go it alone. He secured moderate backing from former racing great turned Holden/BMW dealer Bill Patterson. And with his mechanics Garnett Bateson and Bob Gracie, Brock set about ‘Australianising’ the exotic German factory racer in preparation for its appointment at Le Mans on June 12-13.

Fortunately, Bateson had spent considerable time in the BMW factory learning all about the CSL before the corporate change of mind.

With the car stripped to a bare shell, the complex factory-developed electric anti-lock brake system was replaced with a much simpler set-up comprising enormous ventilated disc rotors, Girling multi-pot calipers, improved cool air ducting and dual master cylinders. This allowed easy adjustment of brake bias and, with home-grown Hardie-Ferodo brake pads, would be the least of the team’s concerns in France.

Team Brock also discarded the heavy and complex factory-designed electrical system and replaced it with a comparatively simple design, which worked just as well but was much lighter and easier to work on. It was professionally designed and installed by a local aircraft technician. By the time Team Brock had finished its three months of Le Mans preparations, the fully rebuilt BMW with a new coat of gleaming white paint had dropped another 90kg, which really put the ‘L’ in ‘Leicht’.

In early June, the car and its numerous spare parts were loaded into a Qantas jet for the long flight to the UK. Special arrangements had been made for the cargo hold to be pressurised to allow Bateson and Gracie to travel with their precious cargo.

After being unloaded in London and into a borrowed transporter for the drive to France, a dispute with Customs officials resulted in the BMW’s spare parts going missing which would have a major effect on Brock’s fortunes at Le Mans.

Aussie international (and future Le Mans winner) Vern Schuppan was originally chosen to share Brock’s BMW in the 24 Hour. However, when that deal fell through his replacement was UK-based Aussie touring car veteran Brian ‘Yogi’ Muir. He not only had Le Mans experience but in previous years had also been a leading 3.0 CSL racer in Europe and the UK and was keen to assist the budget-priced Aussie campaign.

The funding was so tight that Brock had to qualify for the race on a set of old tyres fitted to the car when being transported. Even so, he easily qualified mid-field with numerous other European-based BMW entries in the Group 5 division.

It was during practice that Brock discovered his Aussie-built BMW was capable of tremendous top speeds, which was a great asset given the infamous Mulsanne Straight in those days stretched for no less than 5.0 kilometres. Such impressive velocities were attributed to its light weight and the earlier-specification rear bodywork that came with the car, which was narrower and slipperier than the latest specification which with rear-mounted radiators was considerably wider.

In David Hassall’s excellent book ‘Brocky’, which provided valuable reference for this story, Peter provides some fascinating insights on his Le Mans debut. They also reveal that with a bit of luck, the Aussie 3.0 CSL could have achieved a result well beyond expectations:

“The car was very quick, even compared to the works cars. We actually set the fastest BMW lap time during the race, so the car was no slouch at all.

“We stayed with the old-style rear flares, but did fit a new, bigger front air dam. We also had a Frenchman helping us and he modified the rear deck wing. The car was very twitchy all weekend, though, and it wasn’t until after the race that we discovered it was fitted upside-down!”

Despite the car’s speed, the 24 Hour race began disastrously for Peter. The car felt a little strange on the parade lap before the rolling start and, as he accelerated past the pits for the start, a huge bang from the back of the car signalled that a half-shaft had broken. Peter had to limp the 13.6 kilometres back to his pit for repairs to be made.

With no spares, however, this was a big problem. Replacement parts were borrowed but they were not modified to take Team Brock’s Australian brakes. There was no option but to block off the brake on that side of the axle and go back into the race with the prospect of running 24 hours with braking on only three wheels.

"Of course it was fairly strange for the first few laps with the brakes like that, but we got used to it and it actually braked quite truly. We ran like that until the car stopped after 18 hours and the brakes had still lasted. What's more we got twice the pad wear of the factory cars - using the same type of Hardie-Ferodo pads we used at Bathurst. They were magic.

“The cars themselves, however, were fairly fragile for that sort of race – the engines were only guaranteed for 1000 kilometres and we’d done probably 2500km when the cylinder head gasket blew. I thought about plugging around just so that we would finish, but the engine had damaged itself too much. There wasn’t enough time to replace it, so we had to retire.

“We’d made up a lot of ground before we retired and at one stage we were the last healthy BMW still running. That made the BMW people take a bit more notice of us. Looking back on the race, I guess we did a lot better at Le Mans than I thought at the time.”

Team Brock tackled a 1000km race in Austria a few weeks later, but an early engine failure brought its ambitious overseas plans to an abrupt end. Even so, the mighty 3.0 CSL will always hold a special place in Australian motor sport history, as it allowed two of the nation’s greatest touring car drivers to prove that their talent and home-grown skills were unquestionably world-class.

Under 3.0 litre Touring Cars: The Australian Connection

The sleek C9 coupe range, on which the mighty 3.0 CSL was based, was not sold in Australia and therefore not eligible to compete in local Group C touring car racing at the time, but its E3 sedan stable-mate did grace local BMW showrooms in the 1970s.

Not surprisingly, for a marque that claimed to be ‘the ultimate driving machine’, some of these rorty six cylinder sedans did appear on local race tracks in the mid-1970s. The good news for potential E3 BMW racers was that sub-3.0 litre touring car racing was enjoying unprecedented growth and publicity. The bad news was that the cars to beat were Ford’s 3.0 litre V6 Capri and Mazda’s 12A rotary RX-3.

Despite vastly different engine designs, the Capri and Mazda shared similar power outputs of around 180-200bhp in Group C trim and similar racing weights of around 950kg for the Mazda and 1000kg for the Capri. The Mazda’s lighter weight was largely negated by the Capri’s greater power and torque, so the competition between the two marques was intense.

The considerably larger E3 BMW sedan, which raced in both carburettor 3.0S and fuel-injected 3.0Si specifications, had more sophisticated four-coil independent suspension, four-wheel disc brakes and could match the power outputs of the Capri and RX-3. However, it could not overcome its major handicap – weight.

Tipping the scales at more than 1300kg in showroom trim, the big Beemer was giving its Ford and Mazda rivals a massive 300kg free kick. Unfortunately, unlike its coupe sibling in Europe at the time, there was no local factory support or the option of a lightweight Karmann body-shell, so BMW’s executive express faced an uphill battle from the start.

Its first appearance at Bathurst was in 1974, when Geoff Perry and Fred Sutherland teamed up in a privately-entered 3.0S. The fastest RX-3 and eventual class winner set pole position at 2min 51.7 secs, compared to the BMW which qualified 10th (and last) in class with a best time more than 10 seconds slower. It lasted only 29 laps in the race before retiring with brake problems.

Two years later another E3 sedan tackled the Mountain, in the form of a 3.0Si for BMW 2002 sports sedan racer Paul Older and motoring journalist/racer Barry Lake. Older enjoyed lucrative backing from tobacco giant WD & HO Wills through its Craven Mild cigarette brand, so the immaculate gold and white car looked like a winner standing still.

The Capri vs Mazda fight was in full swing, with Barry Seton stopping the clocks at a blistering 2 min 38.1 secs to secure pole position in his Capri. The fuel-injected BMW was the only car other than a Capri or Mazda in the class and although qualifying 10th out of 11 starters, Older’s 2 min 44.1 sec effort was ‘only’ 6.6 secs slower than pole this time. After a steady race, the Craven Mild car finished a respectable sixth in class, albeit nine laps behind the winning Seton/Smith Capri.

The E3 BMW’s best showing at Bathurst came the following year, when the potent driver pairing of Phil McDonell and Jim Hunter shared a 3.0Si. The BMW’s improving competitiveness was noted during practice, when it qualified seventh fastest out of 15 entries and was now 6.0 seconds away from another Seton pole. The BMW’s consistent pace and reliability also paid off in the race, steadily moving up the class leader board as other cars dropped out to claim a fine third some six laps in arrears and 14th outright.

Encouraged by their podium place the previous year, two 3.0Si sedans fronted for the 1978 race crewed by Phil McDonell/Lynn Brown and Jim Hunter/Barry Lake. However, in stark contrast to 1977, both cars retired from the race before the 27 lap-mark with engine failures.

With New Six production having ceased in 1977, the last Bathurst appearance by a 3.0Si came in 1979 but it was a disappointing curtain call for the lone Lynn Brown/Brian Boyd 3.0Si. After showing surprising speed in the race, it was excluded from the results after post-race technical checks revealed a gearbox irregularity that was outside the rules.

One can only wonder what might have been had BMW offered a lighter variant of the E3 sedan for local touring car racing, given the admirable performance of the standard version against smaller and lighter foes. Even so, it paved the way for the magnificent 635 CSi coupe which erupted onto the local scene in 1981.