Volvo 122S: Swedish star that could have been a ‘V8 Supercar’

By

MarkOastler -

13 January 2015

The Volvo 122S was driven by some big names in its day, including Kevin Bartlett and John Harvey who would both later become Bathurst winners. Here their ‘works’ 122S entered by NSW Volvo dealer, British & Continental Cars, flies down the Mountain during the 1966 Gallaher 500. It was a frustrating day for the talented pair due to a mysterious power deficit, the cause of which was only discovered during a post-race engine teardown (see story).

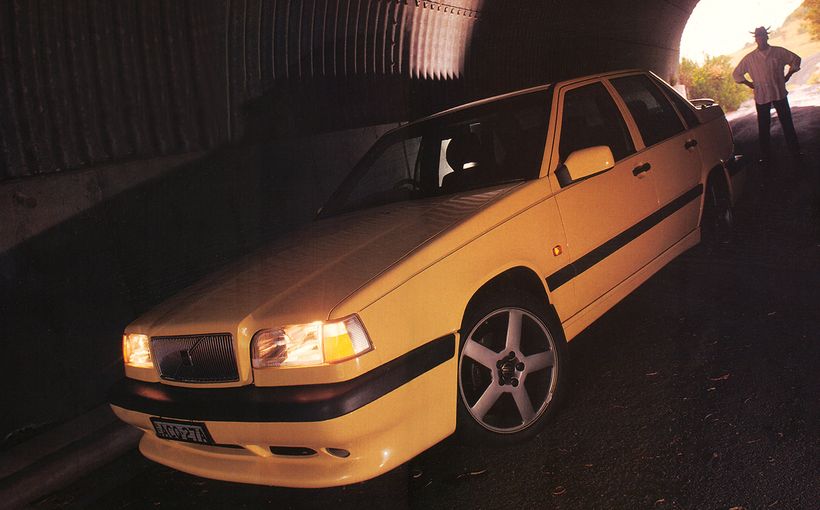

The Volvo S60 competing in V8 Supercar racing today is a unique hybrid built purely for this form of competition, as the Gothenburg-based company has never made a V8-powered S60 sedan for road use. However, had a 120-series prototype become a production reality in the 1960s, Volvo could well have had a genuine V8 Bathurst contender straight off the showroom floor.

Back in the early 1950s, Volvo was experimenting with concepts that could appeal to the lucrative US market which prompted young Swedish designer Jan Wilsgaard to create an ideas car called the ‘Philip’ powered by a compact 220cid (3.6-litre) V8 of Volvo’s own design and manufacture.

This cast iron, overhead valve, 90-degree V8 had a two-barrel carburettor, cross-flow heads with siamesed centre ports and a rugged five-bearing crankshaft claimed to have more main bearing area than a small block Chev. It was rated at 120 hp (89kW) at 4000 rpm with 192 ft/lbs (260Nm) of torque at 2200 rpm.

It was a simple and rugged design that would have responded well to performance upgrades. With cast aluminium inlet manifold, water pump housing and timing chain cover, its weight of 518 lbs (235 kgs) compared favourably to Chevy’s defining 265 cid (4.3 litre) small block V8 of the era at around 260 kgs.

The Philip concept car never reached production but its stout little V8 engine did, being put to work as both a 120 bhp truck engine and 180 bhp ‘Penta’ marine engine.

Although Volvo and Yamaha jointly developed a V8 for the XC90 SUV in 2005 (and later S80) the safety-obsessed Swedish marque has never made a sedan powered by a V8 entirely of its own design and manufacture. However, had tests of a 122 fitted with this small block 220 cid (3.6 litre) V8 been successful, Volvo’s global brand image could have been very different. Note the central runner on the cast-iron exhaust manifold that shared gas flow from the two siamesed central ports, which at first glance makes this look like a V6. Also note the lightweight aluminium inlet manifold, timing chain cover and intricate water pump casting at the front of the engine. Image: www.forums.turbobricks.com

By the late 1950s, Volvo engineers were seeking an upgrade for the 1.6 litre B16 four cylinder in its latest 120 series sedan which had been released in 1956. The company’s 3.6 litre V8 looked to be an attractive option.

“They actually put one in a 122 and road-tested it,” local Volvo identity Gerry Lister told Shannons Club. “I remember the rep from Sweden coming out and telling me all about these V8 experiments they did, which would have been in early 1960.

“As you can imagine it was pretty quick in a straight line but I was told it kept going in a straight line when it got to the first corner. The V8 made the nose of the car heavy and caused too much understeer, so that was that.

“Then someone figured that since they’d gone to all the trouble of building a 3.6 litre V8, why not just cut one bank off it and make a 1.8 litre four cylinder using the five main-bearing crank and that was the basis of the B18 (which was fitted to the 122S).

“The little B16 was a lovely free-revving engine but with only a three-main bearing crank and so forth they couldn’t get a lot of power out of it. That’s why the B18 was such a tough motor because it kept the V8’s five-bearing bottom end and all. You just couldn’t kill ‘em.”

Although a V8-powered Volvo 120 series never went into production, a model called the 122S with ‘half a V8’ under the bonnet was sold in Australia from the early 1960s and quickly established a reputation for outstanding design, build quality, driving comfort, handling and durability.

Open wheeler and touring car ace Andrew Miedecke cut his racing teeth aboard this 122S two-door in the early 1970s, seen here in a torrid dice with Geoff Hunter’s VG Valiant Hemi Pacer at Sydney’s Warwick Farm. Miedecke was working for Sydney Volvo dealer Brayson Motors at the time which offered the cash-strapped youngster much help, but he soon decided that his immediate racing future was in single-seaters and moved on. He would return to tin-tops later though.

Keep in mind, this was long before the infamous rubber-bumpered 240 series Volvos of the 1970s and 80s (along with those who drove them) became the butt of a billion jokes. ‘Bloody Volvo driver’ was not part of local vernacular in the early 1960s. In fact, being a Volvo driver back then showed subtle good taste and worldly appreciation of finer things.

Although not well known in Australia at the time, the Volvo 122 was already a star of European racing and rallying, having claimed Swedish and German touring car championships, the European Rally Championship and outstanding results in major rallies held as far afield as Canada and South America.

By the early 1960s the stylish 122S was available in Australia. Its 1.8 litre four equipped with twin SU carburettors produced a lively 90bhp (67kW) mated to a tough and sweet-shifting four-speed manual gearbox.

It also featured strong yet supple four-coil suspension with a well located live rear axle and powerful front disc brakes wrapped up in a kerb weight of around 1060 kgs. Even though that resulted in a less than ideal power-to-weight ratio for the race track, the stylish Swede was ideally suited to Australia’s rugged roads and soon created a loyal following.

Volvo stalwart Gerry Lister racing a 122S two-door at Sydney’s Warwick Farm in 1966. According to fellow Volvo racer David Seldon, this car was owned by Sydney solicitor Peter Knudsen and prepared by Lister. Scuderia Veloce boss David McKay and Bill Orr drove a similar car to outright victory in the 1966 Lowood 4 Hour race in Queensland, winning by more than a lap from strong GT 500 Cortina and BMC competition. That car had been specially prepared for competition use by the factory in Sweden, featuring a powerful 140 bhp engine, close-ratio gearbox, uprated suspension and big 18-gallon (82-litre) fuel tank. It could do 120 mph (190km/h) and had excellent fuel economy.

Race on Sunday, Sell on Monday

The name Gerry Lister is synonymous with Volvo in Australian motor sport. Lister became an instant fan of the Swedish brand after his first drive of a 122 in the early 1960s. He has been galvanised to the marque ever since and still runs a thriving spare parts business specialising in classic Volvos.

In 1961 Gerry's brother Tony and his business partner co-founded the first Volvo dealership in NSW, establishing British & Continental Cars P/L (later Monaco Motors) on William Street, Sydney. Gerry came aboard later to run the service division. As Volvo was little known in Australia at the time, the Lister brothers decided that motor sport would be a great way to show the public what they could do.

Gerry holds the unique distinction of being the first driver to race a Volvo in Australia. That occurred at Oran Park in 1964 and his appearances at other Sydney tracks like Warwick Farm and Amaroo Park became more frequent.

He was often joined by David Seldon, who worked for British & Continental Cars as a junior salesman and bought himself a 122S to compete against the boss. Another prominent 122S racer was Max Winkless, who worked for the Australian importer Peter Antill at the time and shared his fellow racers’ passion for the Swedish marque.

Volvos everywhere! Several 122S sedans were let loose at Sydney’s new Amaroo Park circuit when it hosted its first open meeting in April 1967. Gerry Lister (left) and David Seldon (right) fight for the lead as import manager Max Winkless has a huge spin behind them. The coverage by Racing Car News magazine was most enthusiastic. Titled ‘Volvos Star at Amaroo Premiere’ the race report proudly stated: “Boy, those Volvos! In two races they electrified the crowd, leant on each other, upset the stewards and…must do it all again. It was dangerous without being foolish and incidentally a fine advertisement for Volvos.” Probably not the sort of advertising the conservative and safety-conscious Swedes back in Gothenburg had in mind, though.

“They were just sensational and they handled beautifully,” Lister told Shannons Club. “Everyone said they looked like they were going to tip over on the track because of the body roll, but that was just because they had fairly soft springing but so much cornering grip. They literally cornered like they were on rails.

“The Swedes said that in Europe they had icy roads so they provided enough body lean to really dig the shoulder of the tyre in. They said if you start putting sway bars on the back and so forth to reduce the body roll you’ll kill the handling. So on the circuit we never tried to stop it. We also set the rear a good 20 percent softer than the front (softer shocks, lower tyre pressures etc) and that eliminated any understeer and gave you complete control.

“The 122 was an amazing car, beautifully designed and with a huge heart. On paper it didn’t go and shouldn’t have been able to do the things that it did with only 1.8 litres, but it was so well balanced. Everything just clicked. I thought those Swedes were very smart and after all these years I still do.”

The annual 500-mile (800km) race for stock standard production cars at Mount Panorama, Bathurst provided the best opportunity for British & Continental Cars to demonstrate the attributes of the 122S to the Australian public.

Although it didn’t win its class, the 122S earned great respect from spectators for its reliability and great praise from drivers for its leech-like cornering grip, excellent braking and ability to be driven as hard as it could go for hours on end without complaint.

British & Continental Cars’ first crack at Bathurst in 1965 was with this 122S shared by experienced hands Bill Ford and Des West. The car’s reliability was faultless, finishing fifth in Class D and 12th outright. It could not match the pace of some class rivals though, headed by Ford’s Cortina GT 500, which finished 1-2-3 in Class D and first and second outright. Bathurst race cars really were stock-as-a-rock in those days, right down to the mudflaps.

1965 Armstrong 500

With the big 55-car field for the 1965 Great Race consisting of four classes based on retail prices, two Volvo 122S sedans were in Class D (£1301-2000) which catered for the most expensive cars in the race.

Enlisted to drive one of the Swedish sedans, which had been prepared by Gerry Lister and entered by British and Continental Cars, were Bill Ford and 48-215 Holden racing star Des West. The other 122S was a separate entry, shared by Graham Ward and Barry Collerson.

The occasional flaw in the Armstrong 500’s price-based class structure, in terms of trying to group together cars that were similar in both price and performance, was clearly evident in 1965.

The other 122S that raced at Bathurst in 1965 was this example driven by Graham Ward and co-driver Barry Collerson. The car was reliable but not fast enough to worry the class-winning Cortina GT 500s, finishing seventh in Class D and 16th outright. Note the overseas number plates on this RHD example, which suggests it may have been a UK import.

If the two Volvos were to have any chance of class success, they would have to overcome 10 of the new Cortina GT 500s, which had been specially designed by Harry Firth to win the race and virtually hand-built in limited numbers to qualify. Class D also included a pair of V8

Studebaker Larks, two works-entered

Triumph 2000s and a lone Fiat 2300.

The GT 500s finished 1-2-3 in Class D and knocked off the S-type

Mini Coopers to claim outright race honours as well. The Volvo 122S pair showed great reliability, outlasting their Fiat and Studebaker competition but clearly lacking the raw speed required to threaten the Cortinas.

Bill Ford and Des West were the highest placed of the two Volvos, finishing fifth in Class D behind the GT 500s that finished first, second and third ahead of the AMI Triumph 2000 in fourth. Ford and West finished a full nine laps behind the class-winning Cortina. Graham Ward and Barry Collerson finished seventh in class and another three laps behind the Ford/West Volvo.

Swamped! The 1966 Gallaher 500 was the last year starting grids were arranged in class order, with the largest and most expensive Class D entries at the front. The S-type Mini Coopers in Class C, which were the fastest cars in the field that year, started right behind the Class D cars yet were swarming all over them by the time the 53-car field reached the first turn. This is the Bartlett/Harvey Volvo getting attacked from all sides by the mercurial Minis as they squeeze through Hell Corner on that first hectic lap.

1966 Gallaher 500

Encouraged by the reliability shown by their lone entry in 1965, British & Continental Cars returned to the Mountain the following year with a pair of 122S sedans.

With the four price-based classes now based on Australia’s new decimal currency, the Volvos were still in Class D ($2701-4000) for the most expensive cars. This included two of the latest

VC Valiant V8s expected to set the pace, plus a Triumph 2000, V8 Studebaker Lark and an

HD Holden X2.

There was a new driving squad for British & Continental this year. Gerry Lister was paired with Ron Porter while open wheeler aces Kevin Bartlett and John Harvey were recruited for the second 122S, after recommendations by Scuderia Veloce team boss and Sun Herald motoring editor David McKay.

Harvey and Bartlett both had previous Bathurst 500 experience so were considered a potent driving combination for the second car. Even so, they were not taking their appointments too seriously.

They might be running close in this shot, but the new VC Valiant V8s simply powered away from the Volvos and everyone else to win Class D at the 1966 Gallaher 500. Here the class-winning Jack Nougher/David O’Keefe VC V8 leads the Bartlett/Harvey 122S through The Dipper. The Valiant’s lusty 273 cid V8 provided a significant speed advantage on Mount Panorama’s long straights. The Volvo’s strengths were braking and handling, but there ain’t no substitute for cubic inches at Bathurst.

“The only testing of the car we got to do was on the drive up to Bathurst from Sydney,” John Harvey told Shannons Club. “Not that you really needed to pre-test Bathurst cars in those days. They were basically stock standard road cars and pretty easy to drive, so the trip up there was all you needed.”

Both of the British & Continental entries were prepared in the same Sydney workshop by Gerry Lister, but the Bartlett/Harvey car was noticeably slower during Saturday’s practice sessions. The team could find no obvious cause for this imbalance, even after a detailed examination and re-tune on race eve.

The Lister/Porter Volvo used its extra speed to run strongly in the early stages of the race before Porter had a huge spin at the end of Skyline on lap 52 of 130. The car slammed backwards into the wooden sleeper fence in the Esses, where it became wedged and could not be recovered.

The Harvey/Bartlett car was off the pace with its mysterious speed deficit but ran reliably to the finish with no other apparent mechanical problems. It finished fourth in Class D behind the VC Valiant V8s that won the class with a thumping 1-2 finish, well ahead of the Triumph 2000 in third.

British & Continental Cars entered two 122S sedans at Bathurst in 1966. This is the car driven by B&CC founder Gerry Lister and co-driver Ron Porter. Lister did not drive the team’s first Bathurst entry the previous year as he was considered too short on racing experience. However, he was more than ready for his Bathurst debut in 1966, teamed with part-time racer Porter who earned his keep as a taxi driver during the week.

“We went there not expecting to do anything special in terms of results,” Harvey admitted.

“So KB and I decided that we’d just drive flat-out and try to break it so that we could get an early mark and go home. So we did that - the only trouble was the bloody thing was so tough it just wouldn’t break!”

Bartlett agreed. “We weren’t going to clutch it (de-clutch at high revs) or crash it or do anything stupid like that because it would have reflected badly on our abilities, but we agreed that we’d drive it at eleven-tenths the whole way.

‘So we were redlining it in every gear and driving it as hard as it would go but it was just unbreakable. The bloody thing just kept going and going without complaint. At the end of the day you couldn’t help but be impressed by that.

“The other car (Lister/Porter) was speedier than ours, it was way quicker. I think even the Minis were knocking us off on the straights, but the corners were alright because you just didn’t lift. The handling and braking were excellent and that’s where we could make a lot of time on other cars. It was a very comfortable and competent car to drive. It just needed more power.”

Ouch! Things did not end well for the Lister/Porter Volvo at Bathurst in 1966, after Porter moved over at Skyline to allow a faster car past but could not regain his line, lost control and spun heavily into the fence in the Esses. You have to feel for Porter as he stands at the rear of the car assessing the heavy damage and thinking that perhaps he’d been too polite. Check out the big kinks in the roof panel and C pillar.

Harvey and Bartlett, with their open wheeler racing backgrounds, may not have been taking their Volvo drive as seriously. However, their egos were more than a little bruised by the superior speed shown by the Lister/Porter team car all weekend. Fortunately, the cause of their speed deficit was eventually discovered.

“They were both great cars, but I didn’t find out until after the event that one of the lobes on the camshaft in the (Harvey/Bartlett) car had gone a bit soft and wasn’t opening one of the inlet valves as far as it should have,” Lister revealed.

“My car didn’t pull away from it much, maybe a couple of metres in 100, but over a longer distance it just walked away. I never thought it would be the camshaft. The night before the race after practice I spent hours re-tuning it so that it was identical to my own. Even then there was still a bit lacking, but there was nothing I could do about it at the time.”

David Seldon told Shannons Club that the performance of the Bartlett/Harvey engine was also compromised due to an error made by a machining shop during preparation of the cylinder block. This required some hasty modifications to the pistons to provide sufficient internal clearances for the race.

Nice view, shame about the race. The Gerry Lister/David Seldon 122S at Reid Park during the 1967 Gallaher 500, before engine trouble halted their run after half distance. The brilliant ‘panorama’ that gave the mountain its name remains, but the circuit is now almost unrecognisable compared to 1967. Note the ‘safety’ fence made from wooden palings bolted to posts driven into the ground. We hope that old tin sign for Champion spark plugs ended up in someone’s prized collection.

1967 Gallaher 500

The Volvo 122S had shown near-faultless reliability in its two previous Bathurst appearances, but its third outing on the Mountain revealed an uncharacteristic engine problem which ruined any chance of a good result in Class D ($3001-4500).

Again, competing classes based on showroom retail prices produced a far from level playing field for the Swedish sedan, as this year it was grouped with Ford’s sensational new XR Falcon GT which ran away to finish 1-2 in both Class D and outright.

Other Class D contenders also blown away by Ford’s booming new V8-powered muscle car were the ageing Studebaker Lark, Alfa Guilia Super, Triumph 2000 and an Audi Super 90. After a solid start, the Volvo 122S driven by Gerry Lister and David Seldon rolled slowly into pit lane after 85 laps with ominous noises coming from beneath the bonnet.

Scuderia Veloce team owner and motoring journalist David McKay became an instant Volvo fan after driving a 122S in the early 1960s. He later sold small numbers of Volvos to well-heeled clients in Sydney’s leafy northern suburbs. However, at Bathurst in 1967 he shared this Audi Super 90 with 1964 winner George Reynolds, here locked in a Class D battle with the Lister/Seldon Volvo. The front wheel drive German sedan finished sixth in class and 16th outright.

“That car was a little beauty (the latest 1967 specification with 100 bhp/75kW engine) and we particularly wanted to knock of (David) McKay in his Audi,” Lister recalled. “I did the first stint and the car was running very sweetly, but it was during Seldon’s stint that he came in and said ‘I think there’s a noise in the engine’. Well there was and it was bearing noise. Turned out it ran a big-end bearing.

“I found out later that Seldon decided he could save a couple of gear changes across the top of the hill by staying in third gear all the way from Reid Park to Forrest’s Elbow (David Seldon emphatically denies this claim).

“You could rev those things to 7500-8000 rpm all day with valve float and all and it didn’t seem to worry them. However, you could get a bit of oil surge in the sump in those days through long fast sweepers like McPhillamy Park, when a lot of oil was suspended up in the engine for a period of time, so you had to be mindful of that (Seldon claims that he advised Tony and Gerry Lister of the oil surge problem but was told to ignore it).

The reliability and consistency of the Volvo 122S really shone in endurance races other than Bathurst in the 1960s. In addition to the McKay/Orr Lowood 4 Hour victory in 1966, Gerry Lister and David Seldon finished seventh outright and third in class in the 1967 Rothmans 12 Hour at Surfers Paradise. Success came earlier for British & Continental Cars when this 122S prepared by Lister won its class and finished eighth outright in the 1964 Sandown 6 Hour race. Driven by Kiwi Colin Giltrap and Ivan Senegin, their winning run was jeopardised when the bonnet catch failed with only a few laps remaining. A quick stop to allow a team member to remove the leather waist belt from his trousers and loop the broken latch and grille together got the car home safely. You can see the slightly open bonnet and securing belt here as the class-winning Volvo crosses the finish line.

“David (Seldon) was a good steerer, he was quick alright, but as David McKay wrote in his Sunday paper column the next week, our car ‘succumbed to over-driving’ and he was dead right. I was furious about it (Lister soon cured the oil surge problem simply by mounting the oil pump pick-up lower in the sump).

“Anyway, I still wanted to be classified as a finisher, so towards the end of the race I jumped in the car, tipped in some oil treatment ‘goop’ and drove slowly around to Forrest’s Elbow and waited just near the clubhouse for the race to finish. Then I just let it roll down Conrod Straight and coasted over the line.” The Volvo finished second last in Class D with 86 of 130 laps completed.

Volvo’s 122 did not enjoy the same success in Australasian rallying as its works cars did in Europe, with local entries generally private or dealer-backed. A stand-out result for an Aussie-crewed 122S was in the inaugural ‘International Caledonia Safari’ held on the tiny Pacific island of New Caledonia in 1967. The narrow victory by rally ace John Keran and motor sport journalist Max Stahl made headlines (above) as it marked the first time an Australian crew had won an international rally beyond local shores. Three years earlier, a trio of 122S Volvos impressed in the gruelling 1964 Ampol Trial. All three cars finished in the top 30 with no major mechanical problems, after more than 11,000 high speed kilometres across Australia’s toughest roads and bush tracks.

1967 was the last time a Volvo 122S would compete at Bathurst as the Swedish manufacturer’s new 140 series models went on sale in Australia that year, with local participation in motor sport focused more on rallying than circuit racing from then on.

Although the 122S did not have the crucial power-to-weight ratio required to be a major threat in local series production racing or rallying, its attributes of quality engineering, exceptional roadholding in all conditions and outstanding reliability certainly shone through.

You can’t help wondering, though, just what kind of high performance car the 122 could have been had Volvo persisted with its V8 experiments of the late 1950s. Sadly we’ll never know.