Given the widely praised sporting prowess of the Fiat 125, it’s not surprising that it posed a genuine threat to the dominant Mini Cooper S at Mount Panorama. In the 1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500 the Fiat 125 driven by Bob Forbes and Peter Finlay came close to finally knocking the mighty Mini off its unbeaten pedestal in Class C. It was the Fiat 125’s finest moment on the Mountain.

And it achieved that after a spirited fight-back, following the infamous multi-car pile-up caused by Bill Brown rolling his Falcon GT-HO at Skyline on the first lap. For a few frantic moments the top of the Mountain resembled an instant wrecker’s yard, which was blocking the track and threatening to stop the race. Confusion reigned and Forbes and his Fiat were stuck right in the middle of it.

“Bob sensibly hopped out with his fire extinguisher because we had been told that if a red flag was waved to stop the race on the first lap, the race would be re-started on the grid,” Peter Finlay told Shannons Club.

“So when he realised the red flag had not been shown and the race was still on, he jumped backed in and trundled back to the pits to check out the car. Everything was fine so we sent him back out quick smart, but this put us a long way behind many of the Class C cars.”

And so began a determined recovery by Forbes and Finlay, driving the wheels off their beautifully prepared Fiat 125 in a day-long battle that resulted in them finishing just over half a minute behind the class leader when the chequered flag fell (read more of Peter Finlay’s recollections later in this story).

It was the best performance shown by the potent Italian sedan in its three appearances at the annual 500-mile (800 km) race for stock standard series production cars, which as you’ll discover owed as much to its meticulous preparation as it did to some excellent driving by Forbes and Finlay and some slick pit work by their crew.

The Unfair Advantage

After five years, the ageless and agile Mini Cooper S was still the premium race package in its class at Bathurst in 1969, back in the days when competing cars were grouped according to their showroom prices rather than the more equitable engine capacity divisions adopted in the early 1970s.

Since its Bathurst debut in 1965, the mercurial ‘flying brick’ had seen off all challengers to claim four straight Class C victories including an outright win. In 1969, it was looking good to keep its perfect score intact.

With a well proven 1275cc east-west four cylinder engine punching around 75bhp (56kW) in a pocket-sized front wheel drive chassis that tipped the scales at less than 700 kgs, the front disc-braked Cooper S was blessed with a power to weight ratio of about 12.5 kgs/kW and staggering levels of handling and braking. With its light weight it was also easy on tyres and brakes and with twin tanks in the boot adding up to 50 litres of fuel capacity, could run long and hard between top-ups.

The Fiat 125 with its spacious four door sedan comfort was a large car by comparison, sitting on a generous 2505mm wheelbase with relative handicaps of a kerb weight exceeding 1000 kgs and slightly smaller 45-litre fuel capacity.

The Mini’s massive 300 kg-plus weight break over its Italian challenger was offset somewhat by the Fiat’s larger and more powerful 1608cc DOHC cross-flow four cylinder engine fed by a twin-choke downdraught Weber (or Solex) carb, that was good for 90 bhp (67 kW) and near 100 mph (160 km/h) top speeds. This resulted in a power to weight ratio of around 15 kgs/kW and a sizeable performance advantage for the Cooper S.

Even so, the 125’s other major strength was its superb four wheel disc brake package, at a time when such desirable hardware was usually found only on exotic sports cars parked in leafy suburbs far from the average Fiat owner.

With widely praised handling dynamics from its combination of a well-located live rear axle, twin wishbone front suspension and Pirelli radial tyres, the superbly balanced and fine handling Italian sedan was considered a worthy Class C contender if the cards fell its way.

Although it was never dealt a class-winning hand at Bathurst, the Fiat 125 proved its impressive high performance credentials in the toughest annual ‘road test’ of them all.

1968 Hardie-Ferodo 500: On a hiding to nothing

The Mini Cooper S was on a roll at Bathurst. With three Class C wins from three starts, including its crushing outright win in 1966 when Cooper S crews filled the first nine places outright, it looked like business as usual in the lead-up to the 1968 race.

Out of the five price-based classes, Class C was for cars costing between $2251-3000 which made running a Mini Cooper S a no-brainer for anyone seriously chasing a win. A total of 14 were entered, with the race organisers consigning six of them to the reserves bench in the hope of attracting more non-BMC entries.

Fortunately they found them, including four of the new Fiat 125s. While the potent Italian sedan was a welcome addition, qualifying times showed how much steeper the Mountain would appear to the Fiat runners when faced with such a formidable race-proven opponent in the Cooper S. It was an unfair fight from the start.

The fastest Minis were lapping in the 3 min 12 secs zone but the fastest of the new Fiats was some six seconds slower and the 125’s reliability over the gruelling 500-mile (800 km) distance was yet to be proven.

The race results told the story. Even though their entries were almost halved by race organisers before the start, Minis still filled the first seven places in Class C with the Fiats and other odd-balls left to fight over the scraps. It was also the Brick’s fourth straight class win, keeping its unbeaten Bathurst record intact.

The Tony Basile/ F.Leggat entry was the best of the Fiat 125s, claiming eighth place in Class C which was seven laps behind the winning Mini. Ninth fell to another 125 shared by Ron Kearns and motoring journo Mike Kable, after spending several laps in the pits for panel beating after clouting a fence.

A blown head gasket consigned the Ernie Johnson/Martin Chenery Fiat to 12th place after a long pit stop for repairs, two places ahead of the Bob Muir/Garry Cooke Fiat that suffered diff and exhaust problems. It hadn’t been a great first chapter in the Fiat 125’s Bathurst log, but things looked brighter with a turn of the page.

1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500: The Finest Hour

Once again the battlelines were drawn between British Leyland’s all-conquering Mini and any new class contender brave enough to throw down a challenge to it.

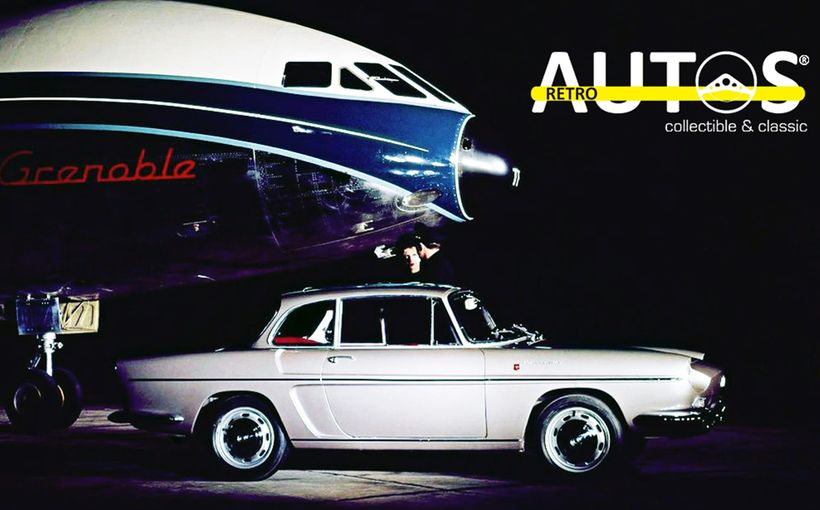

Fortunately, in 1969 there was healthy interest in trying to do just that. With a slight expansion of Class C’s price bracket to cater for cars retailing between $2251-3100, the Cooper S again faced competition from the Fiat 125 plus fresh-faced challengers including the new slant six-powered VF Valiant Pacer, Renault TS16, Mazda R100 rotary and Ford Capri 1600 GT.

Three Fiat 125s were entered for 1969. One was shared by the all-girl crew of Christine Cole and Lyn Keefe, another was for Ron Kearns/Gerry Lister and a third – the focus of our story – was for Bob Forbes and Peter Finlay.

They were good mates with a keen interest in motor racing, having first met during the 1966 NSW hill-climb season. While Forbes stuck with sedans, Finlay moved to the cut-and-thrust of Formula Vee single seaters which gave him valuable experience on Mount Panorama. He also shared a Cortina GT in the 1967 Surfers Paradise 4 Hour race, so had gained valuable endurance racing experience in production cars.

Forbes would later progress to the top echelons of touring car racing driving Toranas in the 1970s, finishing second outright in the 1974 Bathurst 1000 in an L34. He would later run successful Group A and V8 Supercar teams that always maintained peerless levels of presentation.

Finlay followed his dream of overseas success in open wheelers, finishing a close runner-up in the 1973 European Formula Ford Championship. He would later establish the widely acclaimed Nationwide Defensive Driving School and International Racing Driver’s School which he ran with great success in Australia for many years.

According to Finlay, in mid-1969 Forbes did a deal with Les Moon, the managing director of Grenville Motors at Darlinghurst in Sydney, to supply a Fiat 125 for the Hardie-Ferodo 500.

Forbes and Finlay prepared the car with the aid of Darryl Adams; an old school mate of Finlay who owned Adams Automotive in Sydney’s northern suburbs. Adams regularly assisted with the preparation of Peter’s Formula Vee and was a renowned ace with engines.

Ironically, Forbes’ reputation for meticulous attention to detail in his race car preparation may well have opened the doors to a farcical post-race scrutineering incident, which we’ll get to a little later.

“We took the Fiat out to Oran Park for some private practice,” Finlay told Shannons Club. “I took Bob for a few laps and he said that I was a raving lunatic behind the wheel. Then I sat with him for a few laps and suggested the exact same thing! This is often the case when two drivers of equal ability ride with each other.

“I also took the car for a long (intrastate) drive of about 1000 kms to run it in. I do remember at one stage wearing a helmet during this journey, just to get a feel for driving the car with a helmet on which is what I’d be doing at Bathurst of course. It was such a sweet car to drive and didn’t miss a beat.

“During practice at Bathurst our lap times were similar, so with Bob being the prime driver in this exercise he chose to start the race (from 34th grid position out of a bumper total of 63 starters).”

The Forbes/Finlay car was the quickest of the three Fiat 125s in qualifying. In fact, it was faster than all but three of the eight Mini Cooper Ss, which showed that the yawning gap between the Minis and the Fiats that existed at Mount Panorama the previous year had closed dramatically. So why was the Grenville Motors entry so quick?

“The principal reason was that Bob had elected to run Firestone semi-slick racing tyres,” Finlay revealed. “Their grip was clearly superior to the best radial street tyres available and they did not suffer problematic wear at any stage.

“One thing that did concern us prior to the race, though, was that the Mildren Alfa Romeo GTVs had been cracking their steel wheels in other events when they ran race rubber and our wheels were of a similar pattern.

“So in his usual thorough way, Bob discovered that a (metal strengthening) process called ferric nitrocarburising (better known commercially as Tufftride) by Hawker de Havilland could nip any potential problems in the bud.”

As highlighted at the beginning of this story, Forbes was one of many cars to get caught in the enormous pile-up at Skyline on the first lap, after Sydney newsagent Bill Brown rolled his Falcon GT-HO and triggered a multi-car wreck that threatened to stop the race.

Amazingly, by the time the leading Falcons and Monaros came roaring across the top of the Mountain on their second lap a few minutes later, track marshalls had been able to clear enough of a path through the carnage to allow the leaders to carefully thread their way through under caution flags and continue the race.

As Finlay explained earlier, the delays proved costly in lost track position for the Grenville Motors squad. However, unlike many competitors their car had emerged from the incident without damage and knowing they had one of the quickest cars in Class C they put their heads down.

“Bob worked away at catching the others and then it was my turn to make up ground,” Finlay recalled. “I came up on the brown Zanardo & Rodriguez-entered Fiat being driven at the time by clubman driver Ron Kearns. I sensed that he might not have been too experienced at the art of slipstreaming and that I’d have some fun.

“As we drove flat-out and nose-to-tail over Skyline I sounded the car’s horn and flashed the head lights right on down through The Esses and The Dipper, much to the delight of the spectators whose cheering I could hear over the fairly quiet exhausts.

“Down into Forrest’s Elbow I sat right on Ron’s tail then slipped down his left-hand side when he made his first mistake – no self-respecting Formula Vee pilot would have allowed the gift of an inside pass!

“Drawing level onto Conrod Straight, Ron looked at me but I was focused on the road ahead. At some stage I looked across at him and he was similarly focussed so it appeared to each of us that we were ignoring each other.

“Over the infamous second hump on Conrod (which is no longer there) I hatched a devilish plan in which I would draw Ron into Murray’s Corner by braking unusually early. He would, of course, take his cue from me and brake as well. What he wasn’t prepared for was that I immediately lifted off the brake and got back on the throttle so that I had a good car length’s lead on him entering Murray’s Corner and I was away.

“I thought that a Stirling Moss-like ‘thank-you-and-goodbye’ wave would have diffused any angst but after the race Ron was apoplectic. ‘What was all that horn-blowing and light-flashing about?’ he asked, barely containing his ire. ‘It worked, didn’t it?’ was my innocent reply.

As captured by noted Bathurst historian Bill Tuckey in Australia’s Greatest Motor Race, the 1969 Class C battle was a cracker, with two of the Fiats and the lone Valiant Pacer really taking the fight up to the Cooper S.

“So it was the Ryan/Kable Pacer leading early from Ron Gillard in the Cooper S, but some hard driving from Finlay/Forbes got their Fiat up into the lead. By 60 laps the order was Finlay/Forbes, Kearns/Lister and Ryan/Cable, but within 40 minutes the Gracie/Gillard Cooper S had taken over. 20 minutes later the Pacer hit the front.

“The positions kept changing, the Pacer was using up brakes and tyres and spending time in the pits changing them, while the only Capri to survive the first lap had engine troubles. So Warren Gracie and Ron Gillard got the nod from the Fiat 125s of Forbes/Finlay and Kearns/Lister – all on the same lap.”

Despite finishing an excellent second in class and 15th outright, after an intense class battle that lasted more than six and a half hours, according to Finlay the scrutineers suspected that the Grenville Motors Fiat had been a little too quick and had the Italian sedan in their cross-hairs.

“On the Monday, all place-getters were subjected to the usual post-race scrutineering at Gurdon Motors’ workshop in downtown Bathurst,” Finlay said. “It was pretty obvious that the men in white boiler suits and black boots were uppity about something on the Fiat.

“They demanded that we remove the differential and when the stinking lump was on the bench one of the bright sparks inserted a screwdriver into the sun wheels and declared: ‘see, I knew it, you had a limited-slip diff’ to which I responded ‘no s**t Sherlock, funny how the screwdriver wasn’t there during the race!’ Anyway, Bob told me to let it be.

“A week or so later, we were summoned to appear before a tribunal where our star witness was the fellow who had set up the pre-load in the diff using genuine Fiat shims to the manufacturer’s specifications. It was the same way in which he reconditioned all the diffs in the Morris J vans, owned by the bakery company where the chief scrutineer was also the workshop foreman!

“The case was dismissed of course and we were exonerated. Some congratulatory telegrams soon arrived including one from the Ampol Petroleum Company which had supplied all of our fuel and lubricants.”

1970 Hardie-Ferodo 500

The Fiat 125’s third and final appearance in The Great Race reads almost like a post-script as the performance disparity between cars grouped purely on the basis of their retail prices was never greater than in 1970.

With the annual shuffle of classes and retail values, the new Fiat 125S (S for Special) which had been released in May 1970 was eligible for the Hardie-Ferodo 500 in October, but with its greater cost was bumped from Class C up into Class D for cars costing between $3151-4100.

With an engine upgrade that resulted in an extra 10 bhp/7.5kW and the introduction of a five-speed gearbox, the 125S was potentially a faster car than its predecessor at Mount Panorama, with the added benefit of Cromodora alloy wheels which ensured less unsprung weight for even more handling refinement.

Only problem for the 125S was that its greater cost pitched it into a class battle with Chrysler’s new 4.0 litre four-barrel Hemi six VG Valiant Pacer, which had demonstrably more power and performance than the little 1.6 litre twin-cam Fiat could ever hope to match. If the new Pacers were reliable, they would walk it in.

Only one Fiat 125S was entered for Ron Kearns and Gerry Lister; the same pairing that drove a 125 to third in Class C the previous year. The enormity of their challenge was confirmed after qualifying with the fastest of the Pacers setting a class pole time that was a staggering 25 seconds faster!

Yep, at that rate the Pacers would be lapping the Fiat with embarrassing monotony and that’s exactly how the race played out, with the Class D-winning Des West/Peter Brown works-entered Pacer 4BBL (which led the race outright at one stage) finishing six laps ahead of the Alan Cant/Bob Cook Pacer and 11 laps clear of the Fiat in third place.

Perhaps it was such absurdly unfair class groupings that were the catalyst for change to a more level playing field based on more relevant parameters like engine capacity, which were introduced in 1973.

Protect your Fiat. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.