Austin 1800: The Land Crab in a Sea of Barges

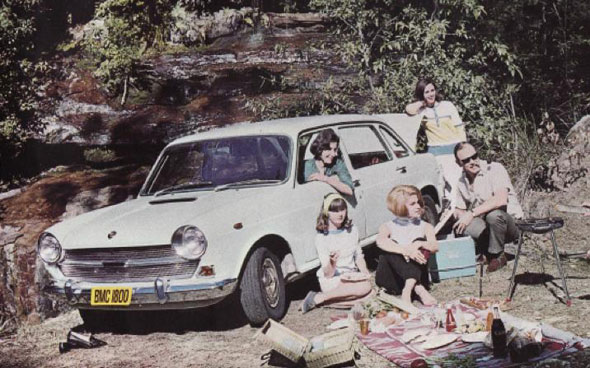

Early brochure shots promoted the Austin 1800 as a six seater with a centre front occupant straddling the front bucket seats and gear lever. The later automatic version with its dash-mounted selector was a genuine six seater with luggage space to spare, an important consideration for an Aussie family car.

Optimistically plugged as “The Car of the Century” 35 years before the 20th century ended, the Austin 1800 lived up to this claim more than anyone could have anticipated. At its launch late in 1965, BMC Australia listed key reasons why its “designers believe it is unlikely that the model concept will be obsolete even in 10 years time.” Virtually every modern passenger car, apart from a few niche models, adheres to the Mini blueprint that was further developed for the Austin 1800.

Such longevity was an important selling point at a time when the US trend towards annual model changes and built-in obsolescence had some real drawbacks for Australians. Most Australians did not have the spending power to change their cars on a regular basis and the value of a car a decade down the track was critical to buying the next one.

Entirely separate to the projected life of the revolutionary Austin 1800 concept was the reliability of the mechanicals. Despite its 1964 European Car of the Year award, the Austin 1800 was not a success in the British market after major reliability concerns eroded public confidence.

The transverse drivetrain and front wheel drive of the Austin 1800 defines the layout of most modern cars. Fluid suspension was interconnected front and rear to anticipate bumps encountered by rear wheels. Note long gearshift cables sitting above exhaust.

The model received a bad reputation in the UK as a serious oil burner that resulted in blown engines. After exhaustive investigations into why such a proven engine should suddenly suffer from this fault, it was discovered that the dip stick was incorrectly marked and overfilled engines were frothing their oil generating the oil smoke and loss of oil pressure.

Also hurting the 1800 in the UK was its extra wheelbase, width and engine size compared to its BMC Farina 1.5-1.6-litre predecessors yet it seemed too small in length and engine size to tackle the premium 3-litre six cylinder market. For Australians, the 1800 was a perfect fit for the growing gap between the 1.5-litre class and the more powerful Aussie six cylinder family cars which were rapidly expanding into a size larger than the British sixes.

Because there was also an extra year of Australian testing to expose reliability concerns, most were addressed in early local cars under warranty while major changes were introduced on the production line. As a result, the local Austin 1800 enjoyed modest success in a market still dominated by Holden, at one stage accounting for 40 per cent of global 1800 sales.

The Austin 1800 was a packaging exercise first, styling came second. PininFarina did well to give it some style as tall engine over transmission defined high bonnet, scuttle and waistline. Note tops of seats below window line.

The Austin 1800 Advances

The Austin 1800 arrived locally at a price just under $2500, almost line ball with the Peugeot 404, its most direct rival. It was also the same price as the HD Holden Special, probably the most cynical family Holden model sold in Australia.

Even at mid-level, the HD’s poor seats, industrial-feel trim, missing heater-demister and lack of instruments were not the worst of it. Rather than increase the wheelbase of the EH before it, Holden moved its engine forward over the front wheels and slumped a bigger body over the same wheelbase and track. Holden’s already poor brakes and handling took a further turn for the worse hence a market receptive to what the Austin 1800 had to offer.

The Mini had proven that a space-efficient two box design with a front-drive east-west (transverse) drivetrain and a wheel at each corner was a winner. The Austin 1800’s challenge was to translate this approach into a spacious family car without the cuteness factor to compensate.

Early Peugeot 204 not seen in Australia styled by PininFarina shared a similar stepped-down bootline and tail lights with the Austin 1800 from the same era. (Image from: commons.wikimedia.org)

In no particular order, this is what it offered:

- Relatively small 1.8-litre four cylinder engine shared with the MGB but detuned from 95 to 84bhp/62kW, about the same as the six-cylinder Austin Freeway it replaced and 9bhp/7kW more than Holden’s 2.2-litre six that was current until 1963. It also featured a sealed cooling system, five-bearing crank and cold and warm air intake. The notion of a more efficient four cylinder engine doing the work of a six is more relevant to the 21st century than it ever has been.

- Its wheelbase of 106 inches/2692mm was longer than both the current Holden and Valiant. Because the engine sat across the 1800’s front wheels, 70 per cent of that wheelbase was allocated to passengers and luggage with legroom still unmatched by many of today’s long wheelbase models. Overall length was much shorter than comparable family cars. Although the 1800 gearbox was mounted under the engine and shared its oil with the engine, most of today’s cars now share this layout except most transmissions and differentials are now mounted to one side with their own oil supply.

- The unusually short overhangs front and rear kept most of the laden weight inside the wheelbase for consistent handling and ride.

- Power-assisted front disc brakes with anti-lock rear drums backed by standard radial tyres, all firsts for an Australian family car and now the norm.

- Four-speed manual with synchromesh on first, not available on any local family car rival.

- The stiffest structure ever for this class of family car with built-in safety and rust-proofed roto-dipped body at a time when most unseen body surfaces in a Holden were not even painted.

- Semi-active all-independent fluid suspension. Although the execution has changed with electronics and new materials, the idea of an interconnected suspension responding to road surfaces and driver needs was an advanced idea and is still a priority in upper level cars.

- The deletion of front quarter windows and the addition of full flow-through face level ventilation backed by a standard fresh-air heater and demister, each with their own air-supply. None were common at the time, especially at the price.

- First family car with three-point seat belts standard. Three-point anchorage points in the rear. Handbrake and other controls were positioned or extended so they could be operated by a driver wearing a seatbelt.

- Cable-operated remote gearshift eliminated traditional noise paths.

- Front and rear door pockets.

- Three levels of dash padding and padded sunvisors.

- Fully adjustable front seats with layback facility for double bed.

- Heavily-padded moulded roof lining coated in vinyl fabric.

- Push-button windscreen washers.

Front styling of the Austin 1800 followed similar theme to Peugeot 204 but rest of the car was quite different as the centre section of the 1800 was defined by the Issigonis design team. (Image from: commons.wikimedia.org)

Austin 1800 Development and Local Input

It is now generally accepted that PininFarina finessed the Austin 1800 exterior during the period that later Ghia-designer Tom Tjaarda was working there. Tjaarda’s work as seen on the rear of his Fiat 124 Spider and the front of his De Tomaso Pantera was known for its sloping edges at the extremities.

The four headlight front of his Ferrari 330 GT was the most controversial application of this style. This feature was later developed into a new corporate look for Peugeot that more or less survives to this day. A variation of this look also appeared on the important first Ford Fiesta completed by Tjaarda while at Ghia.

Just as the Austin-Morris Farina models closely resembled the Peugeot 404, the front and rear of the Austin 1800 previewed the direction of the Peugeot 504. Remove the 1800’s centre-grille bar, attach a centre lion grille motif and combine the 1800’s headlight and surround into a single oval or square headlight and the resemblance is soon apparent.

The two-step boot profile on the 1800 was also established on the rear of the Ferrari 330 GT then later shared only with certain Peugeots including the 504. There was also a resemblance to the 1965 Nissan Cedric (sold locally as the Datsun 2000), another Farina assignment from that era.

Despite this pedigree, the 1800’s appearance was heavily criticized on release as the center section was locked in before PininFarina’s involvement. Today, when so many current models follow a similar layout, the 1800 can look fresher than many of its contemporaries. Yet it is true that the 1800 did look odd in 1965 as most cars on Australian roads had short wheelbases and long overhangs.

Nissan which had previously built Austins under licence was another PininFarina client. This Nissan Cedric/Datsun 2000 from the same era as the 1800 had a clear resemblance at the front. (Image from: earlydatsun.com)

The other decision widely questioned at the time was why the Austin 1800 version was sold here and not the cleaner-looking Morris 1800 version. BMC Australia frequently pictured the Austin 1800 alongside its Morris Mini-Deluxe and 1100 stablemates.

The Morris 1800 with its similar horizontal slat grille seemed a more logical fit. After all, apart from the Austin engine, the 1800 was another variation of the Alec Issigonis philosophy from Morris.

However, BMC in Australia had only just ended the costly duplication of dealer networks that sold the same cars under different badges, a process never completed in the UK because of the close relationship between UK dealers and local villages. Because Morris had been more successful in selling small cars in Australia than Austin, the Morris badge was used exclusively for the local small cars starting with the Mini and Major Elite.

Before the first Holden had an impact, the Austin A40 was Australia’s biggest-selling family car. Because it was followed by an unbroken line of popular Cambridge models, the Morris Oxford version of the Cambridge was merged into the Austin Freeway (which featured the Oxford dash).

It was vital that the Austin 1800 was perceived as a credible local replacement for the six-cylinder Freeway. The Austin badge was one of the few things that stopped Australians from dismissing it as a bigger Morris 1100, which it basically was. Also, the Morris 1800 did not surface until February 1966, after the 1800’s local release. A Morris 1800 version was later built in Australia for the NZ market and local employees were known to fit Morris grilles to their cars, just like today’s Chevrolet badging on Commodores.

Ironically, it was the Austin component that caused most of the headaches both in Australia and the UK.

Early Mark I press shot shows luxurious seating and carpet. Every crevice was exploited for storage including deep dash generated by high scuttle. It needed covers to hide the clutter that owners soon created.

The 1800 engine was the most recent development of the B-series engine that evolved from the original 1940s A40 engine. After it was re-engineered for the MGB, it was a reliable, hard-working engine and following its five bearing crank upgrade, it was by 1965 on a par with the pushrod engines under Holden, Falcon or Valiant bonnets.

However, the bizarre British RAC taxation system (which also applied in Australia) rewarded engines with small bores and long strokes. RAC horsepower could never reflect real output in any way as it was calculated using only the bore and the number of cylinders (bore squared by number of cylinders divided by 2.5). As a result, engines with small bores were taxed much less regardless of their overall capacity and real power output. Australian registration fees and other costs were calculated on these figures for most of the last century penalizing more efficient short-stroke engines.

How much this skewed the Austin 1800’s engine was revealed by its 80.26mm bore and 88.90mm stroke compared to 90.5 and 76.2mm for Holden’s new 179 engine. Cut two cylinders off a 179 and its dimensions would have left a short and powerful 2-litre four, albeit a rough one as the later Starfire engine showed.

If a tall engine was the last thing the Austin 1800 needed, adding a gearbox and diff to where the engine sump was normally located could only make it worse. The design really did require an all-new short-stroke engine similar to the new Holden red engine.

One way of hiding this was to raise the scuttle and bonnet line. PininFarina did well to prevent the Austin 1800 from looking like a snub-nosed truck cab with so little length in the bonnet. The distance between the top of the front tyre and the top of the front guard highlights how much powertrain height had to be hidden. A British commentator compared it to a British Rail shunter.

Morris 1800 Mark I would have looked better in BMC’s local Morris line-up but Austin was the large car badge in Australia. The Morris 1800 was made in Australia but for NZ export only. (Image from: iamo.org.uk)

The local Austin Tasman/Kimberley facelift of this body addressed this with a longer sloping bonnet and boot line to trick the eye away from the tall engine room and scuttle.

The other way of hiding the overly tall powertrain was to allow more of it to poke out underneath. It was this aspect that caused nightmares for local BMC engineers.

Unofficial reports suggest that after a local development engineer bottomed out the front suspension on an outback road, the sump hit the ground with such force that the British engine mounts sheared causing the whole drivetrain to slam back into the firewall and severed the Hydrolastic fluid suspension pipes.

This was in addition to the damage to the powertrain itself, the sheared coolant hoses, fractured brake lines and exhaust system and other downstream body damage. There were also suggestions that the British wheel rims were not strong enough. It was an unmitigated disaster and the race was on to address it.

New engine mounts of a different design were developed along with the fitment of an extra one, the suspension height was raised, a stout sump guard was installed and a much stronger exhaust system was specified. Stronger local wheels were fitted.

The tight transverse engine installation also dictated cable throttle and gearshift linkages, both of which later became commonplace but the idea of a gear lever constantly pushing and pulling on long cables was still new. After the engine mount issues were addressed, further outback development revealed serious problems with the accelerator and gearshift cables. Dust and heat made them sticky.

The later 1800 Mark II reverted to small tail fins and vertical tail lights from the early 1960s while the earlier Mark I on the right had the horizontal tail lights of the late 1960s. Today, the rear of the earlier car looks the more recent. (Image from: commons.wikimedia.org)

The throttle cable travel of the British design was also quite brutal. As soon as the cable became sticky, the shock of the engine responding to the sudden jerks in throttle as the cable seized and let go caused further engine mount and exhaust breakages. The rubber couplings in the drive shafts also began to break-up. All of these were further exacerbated by the lower final drive ratio fitted to Australian examples to improve acceleration.

Australian engineers developed self-lubricating nylon inner cable sheaths and a non-linear throttle-opening mechanism that made the action less brutal at partial throttle openings. The manual choke cable was upgraded at the same time.

Preventing oil leaks where the gear lever cables entered the gearbox was always a challenge but sealing was progressively improved. The transverse layout also dictated a compact clutch design to allow room for a drop gear to transmit drive to the gearbox underneath. After a succession of clutch failures and expensive labour bills to get at it, the clutch was re-engineered but the gearbox itself was better than expected.

Because of the weight over the front wheels, the British specified low-geared steering for their tighter conditions with 4 ½ turns lock to lock. Australian cars had a different steering rack that cut this to around 3.8, later shared with British cars. Early Austin 1800 racks could also feel quite ratchety with a few miles up so this prompted an upgraded design.

Dust-proofing the body was always a worry with British cars and the 1800 was no exception. Attention to local panel and glass fit including tweaking the boot lid was exhaustive and much better than British examples.

An internal bonnet release and a stronger jack were further running changes.

Local Austin 1800 Mark II with its side chrome strip looked a treat presented in a range of optional two-tone combinations. This is one of the very last versions with the repeater lights below the side strip. (Image from: Shannons Club member freeway64)

A Local Wolseley Replacement

Because the local Austin 1800 also replaced the luxury Wolseley 24/80 version of the Austin Freeway, it was upgraded in a number of areas to cover both niches. Front and rear seats were upgraded internally for Australia’s longer distances and wider variations in body shape and weight.

Armrests were fitted to all doors. The luxurious and relatively new expanded vinyl trim and higher quality carpet fitted to the last local Wolseleys were transferred to the 1800 as standard.

The high scuttle dictated by the powertrain was exploited inside with a split level dash featuring strip instruments in the upper level and a large open storage area below. Fake woodgrain was specified in later local cars to break up the acreage of open space and to maintain a link with earlier Wolseleys that traditionally featured real tree-wood dashboards.

A non-slip liner was added to prevent objects from sliding across the full width storage area or launching into the passenger area. A set of shutters would have been more useful as any clutter in this area made the whole car look untidy.

British Morris 1800 Mark II parked next to the local Austin 1800 Mark II highlights how much sleeker the local car looked with the side strip added and overriders deleted. (Image from: Shannons Club member freeway64)

Before the Mark II version was released in late 1968, an automatic option was offered in February 1968 on the last of the Mark I examples. It was the same conventional Borg-Warner Type 35 as offered on the MGB and previous rear drive models but mounted under the engine. Unlike the manual 1800, its fluid had to be separated from the engine oil. It was operated by a cable selector on the dash.

At around the same time, an interim upgrade, sometime referred to as the Series 1 ½, brought several Series II features. These included the fake wood grain dash trim, rocker switches and a box-shaped centre-divider covered in wood grain for the storage area.

There was a Wolseley 18/85 version of the Austin 1800 sold in other markets. The upgraded local Austin 1800 which offered similar appointments in the areas that mattered had made that model redundant.

The relatively frugal and unpretentious Austin 1800 was regarded with great affection until the end in Australia by owners who weren’t impressed by annual model changes and the growing US influence in Australian cars. (Image from: Shannons Club member freeway64)

The Mark II Upgrade

All cars sold in Australia during 1968 had to be upgraded in some areas to meet the latest round of safety requirements. It was a good time to consolidate all running changes in a Mark II version late in 1968. Far more than a facelift, hardly any mechanical or suspension part escaped attention leaving very few parts interchangeable.

Clever tweaking of the grille and parking/indicator lights and deleting the bumper overriders gave the Mark II front a cleaner, more horizontal aspect than the Mark I. However, the bumper overriders had already been removed on later examples of the Mark I to cut costs. A bright side-strip broke-up the slab sides and small tail fins hid the droop in the bootlid.

The jury is still out on whether it looked better but for my money, the fresher Mark II front, the bright side-strip and the original Mark I rear with its horizontal lights might have been a better combination for 1968. It is noteworthy that horizontal tail lights were returned with the Tasman/Kimberley upgrade.

The engine was given a boost in compression ratio, a reworked head with upgraded combustion chambers and bigger inlet valves, a new camshaft and a better inlet manifold. Together, they boosted power to 87bhp/65kW with a small increase in torque. Performance was quite respectable after a new taller second gear (2.217:1 to 2.059:1) exploited the engine’s torquey nature to better fill the gap between first and third.

Spacious interior with comfortable seats front and back was still unrivalled in 1970 although Leyland cost-cutting reduced seat padding and other features. This late example had 14 inch wheels. (Image from: Shannons Club member freeway64)

The lift in performance was quite significant and on a par with the entry Aussie sixes (which by now were hauling much bigger and heavier cars with only three speed gearboxes) with little loss in fuel economy. A longer gear lever and further improvements to the cable linkages allowed cleaner and faster changes. The accelerator pedal was a full pendant design, losing the floor-hinged organ-style pedal that hooked up to the overhead linkage in the Mark I. Steering geometry tweaks reduced the effort of the Aussie fast-ratio steering and suspension changes improved the ride.

Gone were the British Girling brakes. In their place were local Repco-PBR dual circuit brakes including a tandem master cylinder coupled to a new local booster still located separately on the passenger’s side. The new brake bits were regarded as superior to what was there before. The quaint British positive earth electrics and generator were finally replaced by a negative earth system with an Email alternator.

As previewed in the last of the Mk I examples, the dash featured rocker switches, wood grain dash inserts and a wood grain centre-division for the storage shelf. The first of the Mark II examples continued with the extended underdash umbrella-type handbrake fitted to all Mark I examples. During 1969, in preparation for a floor-mounted handbrake, the front seats were modified to create a gap between them. The centre floor-mounted handbrake then arrived later in 1969 leaving some Mark II examples with the earlier handbrake design and the later seats.

Although all British Mark II examples had 14 inch wheels, the Mark II arrived with the Mark I’s 13 inch wheels but these were later upgraded with 14 inch wheels in 1969 which in turn dictated new wheel trims.

Later dash introduced at the end of Mark I had the extra touches expected in a top level British model. Note rocker switches in later cars and dash transmission selector although later centre-mounted handbrake was no longer conducive to seating three across the front.

Late Mark II examples featured indicator repeater lights below the chrome side strip instead of above before the model was withdrawn at the close of 1970. By then, Leyland cost-cutting had removed the rear door pockets, the rear brake pressure valve and reduced the seat padding and carpet underfelt.

Despite few obvious changes, the local Austin 1800 generated a huge amount of media coverage (and sales of almost 60,000) during its five years on the market. At the end, The Car of the Century tag was replaced by First Class Travel, a claim backed by reality.

Its minimalist approach to carrying five and their luggage was often used to assess whether bigger new sixes and V8s represented an advance. In point to point terms, the 1800 was never embarrassed with its comfort, brakes, grip and fuel efficiency.

Those early 1800 owners who survived the big development issues and still motivated to buy the X6 Tasman/Kimberley replacement expecting it to be sorted, were badly let down by another absurd round of failures. As a result, the last Austin 1800 Mark II examples are regarded as something of a high point in this company.

This end of series Austin 1800 Mark II ute offered amazing storage space in huge uncluttered load bed. Heavy loads exposed willing but limited four cylinder engine and loss of front drive traction if the front was lifted. (Image from: commons.wikimedia.org)

The Ute

The Austin 1800 was an unlikely candidate for a ute yet an Australian version was released in mid-1968 as a Mark I with a choice of manual or auto. Stripped of the heater-demister, door pockets and armrests, it also had a bench seat. The manual had an even lower final drive ratio than the sedan.

Its load tray was quite deep with little intrusion from wheel arches which encouraged big loads. Even though the fluid rear suspension was bolstered by the addition of torsion bars, heavy loads would ultimately send the fluid from the rear suspension back to the front and lift traction away from the front wheels.

However, it did generate a niche market for both urban and rural owners who valued the fuel economy and ease of driving for commuting combined with the ability to throw bulky if not heavy loads in the back. It continued with Mark II upgrades that arrived after the sedan in 1969 but always retained the dash-mounted umbrella handbrake.

This rare photo shows a special cross-flow head version of the 1800 engine in a Repco development mule for testing different induction systems including fuel injection. After front bonnet support panel had to be cut away, the external bracing to keep it shut was the only outward sign of the hot engine.

Protect your Austin. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.