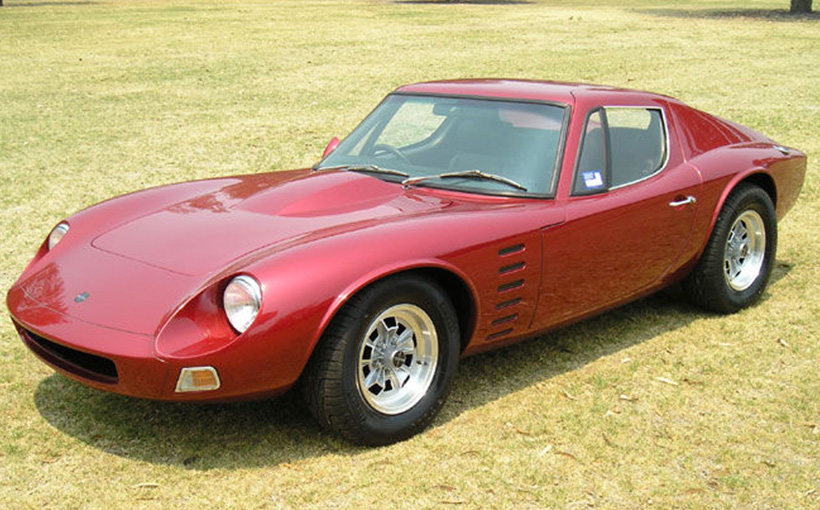

1969-74 Bolwell Nagari: Once a kit car, now a cult car.

The Nagari marked Bolwell’s transition from kit car to factory turn-key sports car. Because of tiny local volumes, the Nagari owed as much to readily available local components as inspired design, highlighting the fundamental difference between it and mainstream factory rivals. Yet the Nagari has stood the test of time as the only all-Australian sports car ever that can boast a production run of four years and an estimated 118 examples, many of which raced successfully.

The Nagari, first seen as a Mark VIII kit powered by anything from a Ford Kent four to a Holden six according to an owner’s whim and finances, was pushed into factory production to protect the integrity and quality of the V8 design. Its Aboriginal name translates to something that flows, appropriate given the fibreglass body and the way it looked. The Nagari badge was used to separate its factory-build status from those before it.

Attempts to rate the Nagari against the Chevrolet Corvette or Lotus Elan, are neither realistic nor helpful as early Nagari examples could never match their factory development and parts. Even the AC Cobra, a mainstream production AC Ace with a Shelby Ford V8 engine transplant, is not a fair comparison. Perhaps the closest in concept and execution was the TVR Griffith, a model that shared an earlier version of the Nagari’s Windsor V8.

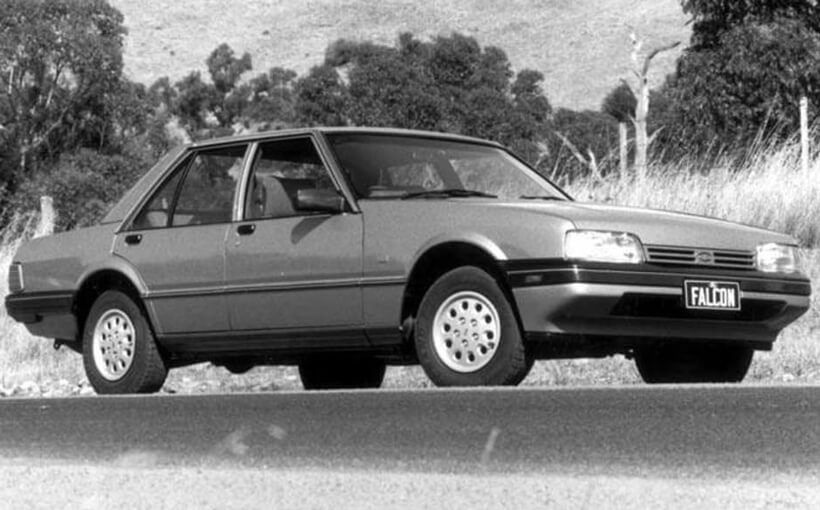

Later examples, once Nagari production gained momentum, were a huge improvement over the early cars after Bolwell ploughed sales revenue back into the cars. The 1970 release price of around $6,000 which had risen to $10,000 by 1974, ensured that the Nagari always cost 30 to 50 per cent more than a new Falcon GT.

The kit cost of $2800 only made sense if you had access to a wrecked XR or XT Falcon GT with a decent drivetrain. Despite the transition to factory production, archival material confirms that the factory would still supply vehicles in various stages of completion. Even a turn-key Nagari demanded a serious commitment from 1970s buyers. Its closest rival, the Datsun 240Z, was only a shade over half the price at the end.

The Nagari was also the first Bolwell supplied with “a round 2-it”, a mysterious part missing from earlier Bolwells. At one stage, it was estimated there were more unfinished Bolwell kits lying in Aussie garages than on the road, because the owner didn’t get “a round 2-it”.

Although Bolwell had been producing cars since 1962, the lack of visible proof of Bolwell’s formidable credentials and experience was a major issue in establishing the new Nagari. Even today, less than 200 of the 800 Bolwells (kits and final production examples) are on the road. Pristine, untouched kits from the 1960s still surface because the owner never got “a round 2-it”!

After launching the Mark VIII at the close of 1969, Bolwell pulled the pin in 1974 just as crash and emissions requirements were about to get tougher. It was an inspired decision. The Nagari was starting to age but had left Bolwell with a clear lead in the fibreglass and composites field. Replacing the Nagari would have been a thankless and funds-busting project.

Bolwell then built the “back to basics” Ikara clubman kit with VW Golf mechanicals located behind the driver. Later projects include the front sections of Kenworth and Iveco truck cabs, Robnell bodies, replica GT40 bodies and a number of OE components for mainstream manufacturers. Bolwell also built a sci-fi range of supermarket children’s rides and supplied the colourful moulded McDonald’s family restaurant furniture.

More recent projects include blades for wind-powered generators, a range of truck aero aids, weather shields and protective casings for outdoor equipment, futuristic camper trailers, and a revival of the Nagari itself.

What was a Nagari?

Campbell Bolwell is often given the credit for the Nagari but his brother Graeme Bolwell delivered the technology leap that lifted the Nagari to the next level compared to its kit car predecessors.

The British kit car industry, driven by tax breaks and aspirations of poorly paid buyers, showed the way. Lotus built an absolute winner with the Lotus 7 Clubman, a model completed with parts from any number of rusted-out small Fords. Lotus then offered its benchmark Elan as a kit to keep its far more sophisticated suspension and drivetrain affordable.

For the Bolwell brothers, it made more sense to exploit the many Holdens that had left Aussie roads. After establishing the striking Mark VII around Holden parts, it was time for Graeme to go overseas and work for Lotus as Campbell took care of business.

As a result, the Nagari is sometimes mistaken as a variation of the Lotus Elan. The two models share a similar backbone chassis capped by a fibreglass body. Graeme also fine-tuned the body-chassis mounting with Lotus-type aluminium bobbins moulded into the fibreglass but the resemblance ends there. Local componentry then dictated Nagari dimensions and the final chassis design.

The Lotus-style backbone chassis, one of the Nagari’s early strengths, depended on the lightweight fibreglass body for side-impact protection, one of the many issues waiting to come back to haunt it.

Bolwell did an outstanding job of Nagari styling behind the hessian curtain at its Seaford facility (a Melbourne bayside suburb near Frankston). It was inspired by ground-breaking designs already familiar to Australians. Even if it didn’t establish new trends, it was still far more daring than the 240Z for 1970.

Elements of the Bolwell Mark VII inspired by the E-type Jaguar were combined with a front and cabin that both drew on the Lamborghini Miura. The alloy wheel design was almost a direct lift from the Miura. Door apertures, rear strakes which created the illusion of long rear pillars and other design details also reflected Graeme Bolwell’s exposure to the new Lotus Europa.

It took considerable skill making the coupe’s short and relatively tall cabin look much sleeker than it was. It also explains why the later Nagari roadster looked a different car as there was no roof to expose the short wheelbase. In fact, the roadster dictated major new body mouldings and chassis tweaks.

The Nagari wheelbase of just 90 inches/2286mm, just two inches longer than a SWB Land Rover, was way too short for the fat front and rear tracks of 57inches/1448mm and 59inches/1499mm respectively. The Lotus Elan had a wheelbase of 80inches/2032mm with a front track of 44inches/1118mm and a 47inch/1194mm rear track.

A chassis design that allowed the relatively heavy cast iron Ford V8 drivetrain (compared to the alloy head twin-cam Lotus four and its single rail Ford gearbox) to be mounted almost front mid-ships was all that stood between a lethal-handling Nagari and one that was acceptable. Many would argue this line was in fact too fine.

Anyone familiar with local family cars would recognise the Nagari’s track figures as belonging to the much bigger XR-XY Falcon series, dictated mainly by the Falcon’s hefty rear axle. The wide but short Nagari footprint ensured an innate twitchiness that would challenge even the best chassis tuners.

Where the Elan had a Y-section at each end to support the ground-breaking Lotus rear struts, the Bolwell chassis had to end in a T-section to support the Falcon’s massive live rear axle that could handle the V8 grunt.

The Nagari design left little room to generate optimum angles for the various rear suspension arms and mounts. Pulling-up that amount of unsprung weight before it could launch the almost featherweight rear section of the Nagari into orbit as it traversed rough Aussie roads, was also a challenge, and then some.

This was less of a concern for track use where the suspension could be screwed down but as an indigenous sports car, the Nagari was expected to cope better with Aussie roads at higher speeds than the average.

Unfortunately, the Jaguar XJ6 which would later provide an almost limitless supply of tough independent rear ends that would transform cars like the Nagari, had only just been released!

Pick a Part

Bolwell’s integration of readily available locally-produced parts was inspirational after they came together as if they were meant to be that way. It was no cake-walk.

Drivetrain: Ideally, Bolwell wanted to maintain its Holden heritage by using Holden’s new lightweight, compact V8 except Holden would not supply Bolwell.

It’s not hard to work out why. Holden’s new V8 was brand new and needed to be kept close to home to sort out any teething issues, of which there were quite a few. Because a local Holden four speed manual gearbox was imminent, an imported gearbox could only be a short term solution. Holden was also busy promoting its new V8 as a sophisticated new engine choice worthy of powering its stunning Hurricane concept car. You could imagine conservative forces within Holden not wanting it associated with a kit car.

Bolwell credits motoring journalist and then Sports Car World editor Rob Luck with negotiating the supply of Ford’s 302/4.9 Windsor V8 and top loader four speed gearbox. This was during the reign of Ford chief Bill Bourke and his competition offsider Al Turner, whose job was to also market a wide range of Ford performance parts under the Super Roo mantra to engage younger buyers. Running a Ford engine under the bonnet of any hot car, kit or otherwise, was exactly what Ford was promoting.

Ford also supplied Bolwell with brand new front suspension uprights and hubs compatible with the Falcon GT’s huge new Kelsey-Hayes ventilated front disc brakes, top-loader gearbox and small block 302/4.9 V8 all fresh from Ford’s current XW Falcon. The heavy duty rear axle was also a local Ford part.

Ford had no problems with diverting an imported crate engine with manual transmission and its Ford number sequence from its most likely Falcon GS destination to Bolwell. Bolwell then developed its own front unequal length wishbones to accept the Falcon uprights and its own rear axle location and springing which were similar to a Torana’s.

A shortened local Austin X6 Kimberley/Tasman rack and pinion system took care of the steering.

The engine was placed so far back in the chassis that the clutch and flywheel ended up behind the windscreen. This forced Bolwell to develop its own short throw linkages to move them forward of the centre armrest leaving them directly above the gearbox inspection plate. Bolwell was one of the few that addressed such issues. Sorting Ford’s own top loader linkages was always a challenge so it was not a task for the backyarder.

Apart from a switch from the stock Autolite carburettor to a two-barrel Holley 500, the US engine was kept factory OE. Even the engine-driven fan stayed although it needed an extension block to reach the radiator in the nose.

The Y-shaped front chassis section crimped space where it was needed most for the V8 exhaust to exit on both sides. Bolwell simply swapped the factory cast iron exhaust manifolds from side to side then flipped them so they exited at the front of the engine but the manifolds were now almost level with the rocker covers.

Bolwell engine pipes had to be routed forward between the block and front cross-member. Because this introduced extra heat high in the engine bay ready for an under bonnet heat soak scenario, the Mark VII-type side vents became more than just a styling link. They were essential to maintain airflow but even then, the heat build-up was too high for the stock cooling system in hot summer traffic.

Given the challenges, it was a clever installation that didn’t leave any wildcards to cause warranty issues if something failed, an outcome not unknown with mass-produced US items at that time.

However, for a Lotus-inspired design that would normally utilise the lightest parts that Colin Chapman could get away with, the Nagari was corrupted by heavy-metal US muscle car mechanicals. The engineering challenges were enormous with a track so wide and components so heavy compared to the rest of the car. It was about to get worse.

Just as Bolwell had developed the Windsor V8 Nagari over successive builds, Ford stopped importing the small block Windsor 302 V8 during 1972. Seizing the gap in Holden’s arsenal after the imported Chevrolet 350 V8 was neutered under new US unleaded emissions requirements, Ford placed a special Geelong version of the Cleveland V8 into local production.

To replace the smaller imported Windsor 302, Ford built a unique Australian 302/4.9-litre de-stroked Cleveland version using the bigger 351/5.8-litre block, a disaster for Bolwell. Although the previous Windsor 351/5.8 could be squeezed in despite its taller block, everything about the Cleveland was bigger.

Holden still would not supply its V8 engine despite a new local four speed gearbox. With a V8 XU-1 under development and the Torana GTR-X still under consideration, Holden was possibly keeping its options open on the Nagari market with a GTR-X V8.

The Geelong 302 delivered more power but Bolwell was left to re-engineer the Nagari chassis for its 351 levels of extra weight and bulk. Such changes were effective from examples numbered in the high 50s to the early 60s except some Cleveland chassis cars were fitted with leftover Windsors in the transition.

The Nagari’s Y-section front rails had to be dropped by a full 2 inches/51mm and the cross member reduced from six to four inches to create the space for the bigger engine. The bonnet was given a bigger bulge to clear the extra height.

Yet the Geelong engine was still too big and high to use the stock exhaust manifolds. Special extractors had to be developed to exit just ahead of the engine mounts. On the passenger’s side, they had to be modified to clear the oil filter.

Because the new engines were supplied to Bolwell from Geelong, not US units diverted from the Ford assembly line, they carried a special AIE (Australian Industrial Engine) number and prefix. Occasionally, a 351 would be slipped into Bolwell deliveries then randomly fitted during Nagari production even though Bolwell remained committed to the 302/4.9-litre specification.

However, such flexibility in specification left more space than most classic cars for later owners to upgrade or finesse their Nagaris for track use or enhance their performance or practicality. Values don’t seem to be too adversely affected providing changes don’t stray too far from the original.

The Geelong 302 boosted performance considerably, but as Allan Moffat discovered with his much bigger Trans Am Mustang, the extra weight and size of the Cleveland V8 were not welcome where handling balance was an issue.

At around the same time, Nagari rear axle location was changed. Earlier cars had coil over shock units, lower trailing arms and upper control arms mounted diagonally via threaded ends with cups and bushes to the outside corners of the rear T-section.

Separate coil springs and dampers replaced the earlier coil over shock units. A new T-section then housed the upper spring mounts while the spring bases worked through the trailing arms. The upper and lower control arms had conventional bushes pressed into them.

Although the improvement over the early cars was dramatic, the lack of precision in the Nagari chassis and instability over bumps remained an ongoing concern.

Body: The first coupes featured solid colours including Ford’s Vermillion Fire and the Mustang’s Grabber Orange. Cadmium Yellow shared with Coca Cola trucks was so popular that it became known as Coca Cola Yellow. Later cars featured metallics including a silver grey, Jaguar blue and the metallic green made popular by the XU-1 Torana. Again, because Nagaris were so often personalised, today’s Nagari market tolerates some variation in this area.

Although there were no bumpers as such, Bolwell integrated easily-replaced nudge sections front and rear. These were painted black on early examples, body colour later, although the rear section was usually left black. Factory replacement rear sections gained over riders as the bootline and rear bumper section were almost flush but this improved design didn’t reach production cars.

Early cars had the recessed front parking/indicator lights from the Aeroflow-upgrade of the Mark I Cortina. Later cars had MGB units which stood proud and didn’t look as integrated. Tail lights were Hillman Hunter, perfect for the job, as they also appeared on the similar rear of the latest Aston-Martin. They were no worse than the Fiat units on the rear of the Lamborghini Miura. Later headlights were Cibie quartz halogen, a big local advance and essential as the Nagari nose left no room for supplementary lighting.

Bolwell’s own alloy wheels originally had alloy centres and steel rims shod with red-walled Dunlop Aquajets. These were later upgraded to a stronger one-piece all alloy design fitted with Avons.

The new roadster involved far more than cutting off the roof. Although barely 18 examples of the 118 Nagaris were built as a roadster, the changes were extensive. Known as the Nagari Sports, the new body was offered from Build no 47 in 1972. Both the chassis and rear body section were strengthened including an internal hoop ahead of the boot aperture.

Other roadster mods included a different inner rear guard design, new reinforced seat belt mounting points, frameless doors and a rear bulkhead moved further rearwards. This allowed extra seat adjustment, addressing the limitations of the coupe cabin. Extra storage behind the seats compensated for the loss of boot space.

Lightweight bodies could be ordered for racing.

Cabin: The Nagari interior never really lived up to its purchase price despite Bolwell’s ongoing efforts and its big advance over earlier Bolwells.

The first cars featured a bleak untrimmed centre console and switch panel, no glovebox lid and a cheap-looking woodgrain instrument panel. A leather-grained instrument panel and glovebox lid were added later. A later padded centre console that extended from the centre armrest up to the dash also made a difference although its toggle switches were still what you would find in an early Mini.

The original drilled alloy-spoked wood-rimmed steering wheel which came from Aussie accessory manufacturer SAAS was a highlight and featured a factory quality Bolwell boss. There was an interim-spec steering wheel that featured the three drilled alloy spokes with a thick leather bound rim and black Bolwell centre. It was replaced by a stark all black two-spoke design with a thicker leather-wrapped rim and the Bolwell centre boss recessed into a flat black surround.

The steering column, dash pad and “Aeroflow” eyeball vents came from the current Mark II Cortina. ADRs later dictated a Valiant collapsible steering column section with integrated steering lock.

Along with the Stewart Warner gauges, it was the Cortina’s crash pad (with family resemblance to the one in the XT Falcon GT and ZA/ZB Fairlane) that saved the cabin from amateur hour status. The special Bolwell sports seats built on shaped fibreglass shells with contoured bolsters, textured inserts and separate headrests were state of the art for the era even if they did slide on XW Falcon runners.

Proper wind-up windows with fixed quarter vents were an important last minute addition after cockpit heat was found to be unbearable.

Because the optional air-conditioning had to be mounted behind the seats, it did a better job of chilling the necks of passengers than dousing the pervasive heat that seeped from the mechanicals around the driver’s legs and the intense Aussie sun exposed through the steeply-raked screen.

Why wasn’t it exported?

After 1972 suggestions that it would go to Singapore and South Africa in various stages of completion (it didn’t happen beyond one-off examples), a LHD Nagari displayed early in 1973 raised hopes that it was ready to sell up a storm in the US.

This sole LHD example was an early cancelled California order before it was presented as the 1973 Melbourne Motor Show car hence some early body details. It was then raced in Australia in LHD before it was converted by a later owner.

New ADR crash requirements including tough side impact standards were then flagged for the local industry for 1974. By September 1973, Lotus, with its much healthier global sales, had killed the Elan as soon as it faced the same challenges elsewhere.

Locally, the Torana GTR-X, even if it never reached production, educated Australians on how a 1970s coupe should look. As described earlier, the Bolwell brothers had the good sense to prepare for a dignified withdrawal in 1974.

The sole LHD example was a cancelled California order before it was presented as the 1973 Melbourne Motor Show car hence some early body details. It was raced in Australia in LHD before it was converted by a later owner.

So did the Nagari transcend a kit car?

Because of close staff involvement in the Nagari’s gestation, Sports Car World magazine (from the Wheels stable) was more kindly disposed to the Nagari than any local publication. In March 1973, when it tested the final specification of the Nagari Sports and rated it against the XA Falcon GT Hardtop, Mel Nichols nailed what any keen driver would have discovered in a test drive:

“The Bolwell still feels rather raw, although you can see and feel how far it is coming with every one you drive. The suspension needs further sorting out to get the precision that is missing now, and to stop that instability over bumps. The braking balance and performance needs development, the steering needs gearing up considerably, footwell ventilation will have to be worked in and a better system of sealing the top around the windows is necessary. A bigger fuel tank would be nice too…”

All was forgiven however, as Nichols claimed “these faults don’t overshadow its gut-twanging appeal.” Unlike Nichols, Nagari owners had to live with one as an everyday driver and even well-heeled Australians baulked at running a $9200 sports car in 1973 just for a weekend squirt. A Jaguar E-type Series III V12 was barely $11,000.

After almost three years of relentless Bolwell development, these faults could only be rectified by purpose-built parts. If Bolwell was able to switch to Holden V8 power in 1972, limited development funds and resources could not only have been redirected to fix these shortfalls, the faults would have been less pronounced with the lighter powertrain.

That Nichols felt compelled to state after almost three years since release “you can see and feel how far it is coming with every one you drive” suggests the Nagari still had some way to go to match factory development levels of rivals.

Because the starting-point was so drop-dead gorgeous and fun to drive, the Nagari is one story with no ending in sight. As Australians prospered and owner needs could be spread over several cars, the Nagari’s failings could be subtly addressed with new parts and technology causing prices and demand to soar.

Protect your Bolwell. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.