1968-73 Fiat 125/125S: Australia’s First Twin-Cam Holden Rival

Australian buyers were given unprecedented choice in 1968. Holden’s new HK Kingswood could at last seat six adults, the new Monaro was a jaw-dropper and the XT Falcon GT became an ongoing model. After the new VW 1500 Beetle arrived with 12 volts and front disc brakes, the Datsun 1600 rewrote the rules for the same money. Yet according to Wheels, it was the Fiat 125 that was “the best car that came our way for two years. At its fully imported price of $2898, it represents just about the best value in the land.”

Wheels would qualify this later “apart from the Big Three compact models and the Peugeot 404” but the message was still clear. The Fiat 125, launched locally in March 1968, was a watershed model. The way it translated high-end technology into the family car segment was a preview of the cars of today.

The Fiat 125 and the Datsun 1600 (which offered BMW sophistication for just $2100) were both carrying full import duty. It could be argued that the year 1968 marked the point when the Australian industry was distorted into making all its bread and butter cars bigger than everyone needed but the price incentives were too favourable for buyers to ignore.

Under today’s rules, the Fiat 125 should have cost $2300 and the Datsun around $1800 before on road costs. Add a zero to today’s on-road prices and it’s easy to see why the Mazda 3, Nissan Pulsar and Toyota Corolla own the passenger car market at one end while the VW Golf and its European compatriots are sealing off the other end at around $23,000.

Imagine by 1969 if a Datsun 1600 or Toyota Corona opened the family car market at $1900 and a Peugeot 504, Renault 16, Triumph 2000, Volvo 144 and an upgraded Fiat 125 defined the next segment in the $2500-3500 range. And even if families still needed a Kingswood, Falcon or Valiant wagon in that $2500-3500 range (just as they buy SUVs in the 25-35,000 range today), the locals would have been compelled to offer disc brakes, radial tyres and better transmissions as standard at least five years earlier to be competitive. Heater-demisters and external mirrors were only fitted during this period after they became a safety requirement.

During 1968, Wheels also tested the new HK Kingswood with 307/5-litre V8, auto and limited slip diff for a total of $2869 but that didn’t include disc brakes or radial tyres. The Fiat 125 was significantly quicker in every acceleration increment including the standing quarter mile (Kingswood 19.1 versus 18.2 seconds Fiat 125).

The Kingswood V8 topped out at 105mph/169km/h versus the Fiat’s 99.5mph/160km/h except the Fiat averaged 22.1mpg/12.8 L/100km while the Kingswood slurped fuel at an average of 11mpg/25.4L/100km.

Both could generate considerably better fuel figures on the open road but the parity remained similar. If the Fiat 125 featured the typical three speed auto of the day, the comparison would not have been so clear cut but Australia was still a manual market in 1968.

Fiat had a five-speed manual up its sleeve in 1968 which would have improved top speed and cut fuel consumption but was obviously walking a tight rope on specs and pricing to post that sub-$3000 price. The five-speed and a tachometer to go with it would have to wait until later.

Pizza Supreme Meets Hamburger with the Lot

Although Italy is rightly perceived as the epicentre of automotive design during this period, it also had to pay homage to American tastes to win vital export sales.

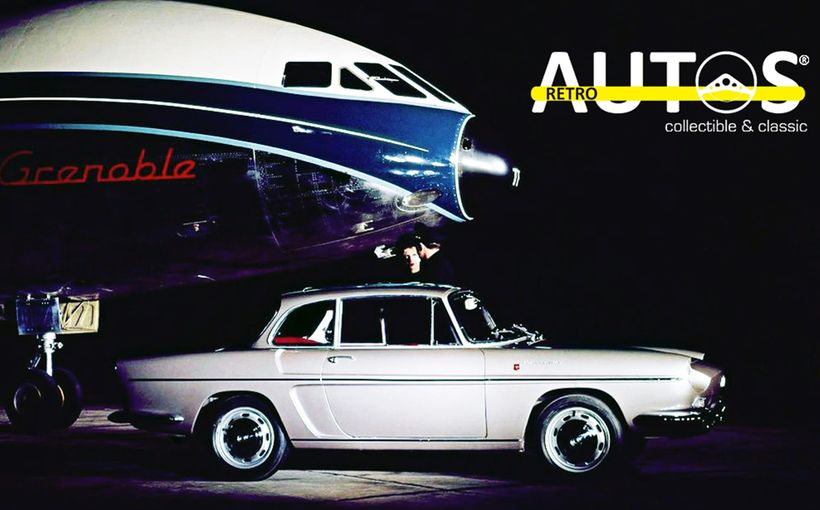

The Fiat 125 was the replacement for the popular Fiat 1500, Farina’s front-engined translation of the Chevrolet Corvair in looks. The smaller Fiat 124, which replaced the Fiat 1100D Riviera (a 1200 in capacity despite the name), arrived in Australia a year earlier in 1967. Its looks suggested that Fiat had only just become aware of early Falcon and Valiant styling.

In fact, the Fiat 124 merged so closely to that of the Vauxhall Viva/Holden Torana, Hillman Hunter and Ford Cortina from the US corporations during this same period, they were almost indistinguishable from the front. The term “international look” was coined as a euphemism for cars that shared this universally bland look.

Fiat had another agenda. The Americans (and some of the UK industry) had established the practice of defining a roof and doors, the most expensive part of a car, then applying it over as many parallel makes and models they could get away with. The front and rear sections along with wheelbase could then be altered to fit the target market or badge.

If the doors were too small for the extra wheelbase, a blank between the rear guards and doors was the simple fix. Extra distance between the front doors and front wheel arches would also hide any disparity. If the roof looked too small, then a thicker C-pillar or extra window behind the rear doors would hide it.

The clever part about the Fiat 124, apart from its advanced feature list, was the big glasshouse featuring four exceptionally wide-opening doors. For a model built on a short wheelbase of just 95.3 inches/2421mm, identical to the first Holden HB Torana, it provided the space and access of a much bigger car.

Although the Fiat 124 was rear drive, its small engine was moved as far forwards as Fiat dared with the front cabin as close behind it as the front wheel arches would allow. A larger than usual turning circle for a rear drive car this small was an indicator of how ruthless Fiat’s packaging of the 124 was.

This left the steering wheel much closer to the vertical and the pedals more horizontal than usual and a direct gearshift on an angle. Although it led to jibes that you needed the long arms and short legs of an ape to drive it, the Fiat 124’s cabin architecture was closer to a front drive model than a traditional rear drive model.

The side profile of the Fiat 124 with its short distance between the front doors and front wheel arches was highly unusual for a rear drive model. In fact, the position of the 124 doors relative to the front and rear wheel arches is almost identical to the later front drive Fiat 128 built on a similar wheelbase.

There was a reason why the cabin and doors almost seemed too tall and too big for the 124.

Although it is often assumed that the 125 was a stretched, more prestigious version of the 124, that wasn’t the case. The 125 was built on the final Fiat 1500C platform after its wheelbase was extended to just under 99inches or 2505mm in 1965, a model that Australians knew as the 1500 Mk III.

Because the 1500C’s direct replacement was the re-bodied 125 version of itself, it explains the 125’s very different proportions and stance on the road, not to mention several differences in cabin architecture and mechanical specifications compared to the 124. It also explains why the Fiat 125 is often described as a big car in the European context as the extra wheelbase delivered a cabin comparable to Australia’s bigger family cars in all dimensions except width.

Like a host of US and British cars, the Fiat 124 roof and cabin were imposed over the different Fiat 1500 platform with more imposing front and rear sections tailored to cover the extra wheelbase and restore some balance in looks. In appearance terms, the 125 mirrored the relationship between the 1966 US Falcon and 1966 US Fairlane, which, unlike the local Fairlane, didn’t share a panel beyond the front and rear screens.

The US influence could also be seen in the 125 nose despite the unusual quad square headlight arrangement and again, seemed to reflect where Chrysler was in 1963. The unusual pair of twin vertical tail lights mirrored US trends for sequential lights as featured on the Mustang.

The extra wheelbase changed the engine and cabin relationship ever so slightly for better handling balance. A new remote control gearshift catered for the slightly more relaxed seating position and generated space for a centre console. In typical Fiat fashion, the 125 handbrake was left close enough to the gearshift for a keen driver to skin their knuckles.

Fiat also tuned into the latest Mercedes-Benz dash design that was becoming a benchmark across the industry and would soon be seen in a range of Audi and VW models. Most driver functions were controlled by three stalks and there was a hand throttle and intermittent wiper function, all relatively new to Australians in this price range. Wood grain trim, wide padded under dash parcel shelf and comfortable seats with intricate-looking trim added to the wow factor at the price.

It was also one of the first affordable family cars after the Cortina with flow-through ventilation with extractor vents in the C-pillars fed by the perforations in the roof lining.

For this market, the big clock sitting next to the speedo seemed to make more sense but local testers were soon screaming for a tacho as soon as it was discovered that the engine was the real bonus in any 125 deal.

By 1968, Fiat’s new twin cam engine was built in massive volumes for the 124 Coupe, 124 Spyder and a volume 125 family sedan for huge savings in manufacturing costs. Unbelievably at the price, it had a twin-cam cross-flow alloy head with a twin-choke downdraught Weber 34DCHE(or Solex C34 PAIA/3 depending on the mood of the Italian supply chain) on one side and a proper extractor exhaust on the other. No wonder Fiats from this era had an exhaust crackle to die for.

It was also one of the first with a toothed timing belt for silence and weight reduction and clever bucket and shim tappet adjustment that didn’t require the lifting of the cams.

It is often claimed that Fiat simply fitted the 124 Coupe’s twin-cam engine to the 124 sedan to create the Fiat 125. Not so. A young Chris de Fraga in the April 1968 issue of Motor Manual explained it at the time:

“The 125 motor puts out 90bhp(net)/67kW at 5600 rpm from its 1608cc. This compares with 90bhp (net) at 6500rpm from the 1438cc motor of the 124 Coupe and Spyder and the 60bhp (net)/45kW at 5600rpm from 1197cc in the Fiat 124. All three motors have basic similarities in the bottom end to permit them to be machined on the same lines at the Fiat factory – with consequent lower cost.

“The 124 and 124 Coupe engines share the same crankshaft but the 124 Coupe unit has bigger cylinder bores. The 125 motor has the bores of the 124 Coupe but a longer stroke crankshaft. At the top end of the motor, the 124 Coupe and the 125 sedan share the same valve gear and fibreglass belt drive.”

This relationship didn’t last for long as the 124 Coupe was soon upgraded with a sportier version of the 125 engine. Yet the point remains. Fiat tailored each of its engines specifically for each application while maintaining amazing economies of scale. That 90bhp was real horsepower, and would have been as much as 25 per cent higher if quoted as a gross measurement more commonly used in Australia at the time. This would explain why the 125 was much faster than the Datsun 1600 despite that car’s higher claimed power figure and lighter weight.

Unlike most mass-produced engines in 1968, the 125 engine sang all the way to 6500rpm without any vibration periods. It was a revelation to Australian drivers and the 125 along with new Renaults, Volvos and Peugeots created more than a few cracks in local loyalty for the US way of doing things. By 1972, this had gathered such momentum that all local manufacturers missed the strong swing towards Europe.

Instead of the 124’s coil spring live rear axle, the 125 remained with the 1500’s rear leaf springs, with trailing arms/track rods providing additional location. Given the huge difference between the 125’s laden and unladen weight, the twin leaves in each spring were Fiat’s best chance of a variable spring rate.

Testers at the time agreed that it worked superbly on gravel roads. Although the front end was a double wishbone design, Fiat had picked up the US idea of a strut-type upper mounting for the dampers that sat on the upper wishbones.

Add in power-assisted four wheel disc brakes, alternator, halogen high beam head lights, brake proportioning valve, the intermittent wipers, electro-magnetic fan coupling, fully lined boot and Pirelli’s new Sempione cross-ply tyres, and the 125 soon provided a comprehensive list of what was missing in local cars. The main shortfall was the worm and roller steering, a design often specified to isolate road shock. In the 125, it wasn’t entirely successful in this respect while sacrificing the accuracy of a good rack and pinion steering.

Last but not least was the unusually light weight of just over 19 cwt or just under a 1000kg in today’s terms. Because the engine sat well over the front wheels, it settled down nicely with some weight on board. Its light weight was quite an achievement but it came at a cost later. Fiat had one more 125 card to play.

When Special Meant Special

As local manufacturers struggled against a renewed onslaught from Japan and Europe, life got much tougher for importers like Fiat. As the 125’s price crept up to $3058 in 1970, Fiat offered a new 125 Special as a $3568 prestige choice in May 1970.

It was a move vital to the 125’s local survival as the entry 125 was gone by February 1972 yet the 125 Special survived until April 1973 ready for the more substantial 132 to take over.

The 125 Special or 125S was indeed a special car and delivered well beyond the modest price premium. It featured Cromodora alloys with Michelin ZX radials, steering lock, laminated windscreen, electric rear window demister, push-button radio with speakers front and rear, and an electric aerial. Heady stuff for early 1970!

That was the start of it. Seats were upgraded with cloth inserts, the clock was relocated across the dash and a large tacho took its place. The new five speed gearbox dropped engine revs at cruising speeds dramatically.

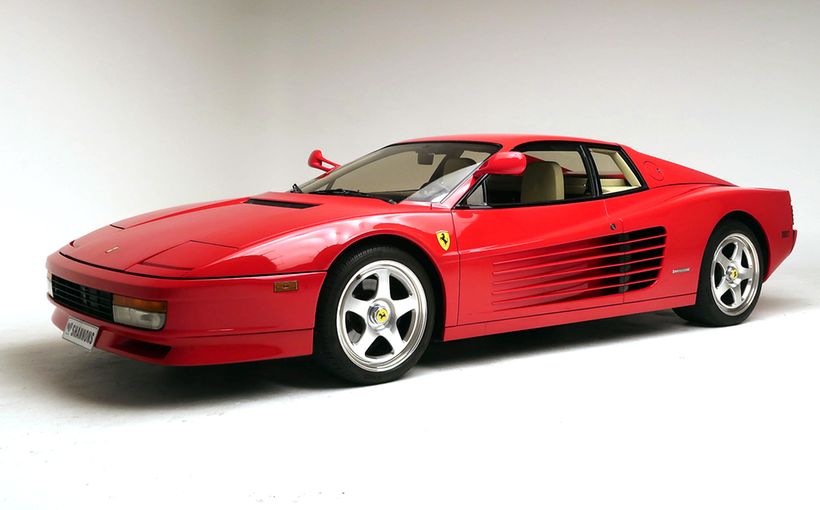

The real difference was under the bonnet. Some tweaks to the head, camshafts and inlet manifold boosted power to a genuine 100bhp/75kW. Its 105mph/169km/h top speed was close enough to any Holden V8 this side of a Monaro GTS 350 with useful improvements in the 125’s already exceptional acceleration figures. And even if fuel economy actually improved, that didn’t stop Fiat from boosting fuel tank capacity by another five litres.

Although the 125 had already established a steady market with young married enthusiasts with a future margin for the arrival of young children and older drivers with grandchildren, the 125S could now be shopped by both genders of all ages against a number of sporty coupes while delivering the extra practicality of a sedan.

It received a less than successful facelift in December 1971 that brought a fussier grille and front indicators recessed into the lower edge of a rubber-capped front bumper. Bigger tail lights made it look boxier.

Because it finished in April 1973, it narrowly escaped the disaster that the entire Italian industry courted by sourcing dodgy Eastern European steel.

How did Fiat 125 do it for the price?

Because the Fiat 125 had come and gone in Australia within five years, it was not yet as obvious as it was in other markets where Fiat cut the corners.

The 125’s light weight was a product of thinner panels. Whether it was because what was there was more stressed or the rust-proofing wasn’t as extensive as it needed to be, the Fiat 125 soon gained a reputation for rusting-out even locally, although nowhere near as badly or as quickly as later Fiats, Lancias and Alfas.

Headlights tarnished earlier than they should have and this dragged down the presentation and general respect for the model earlier than it deserved. Some paint colours did not survive in the Aussie sun and the seat trim and padding was temporary, a product of the extensive heat-stitching that fell apart as soon as the sun got to it. Dash tops were vulnerable to cracking and the wood grain could soon start puckering at the edges.

Yet the mechanicals were unusually good if they received specialist attention. As one of the first with a cam belt, the Fiat twin cam would soon punish those who did not heed the importance of changing the new-fangled belt when specified.

Although not the engine’s fault, it was also vulnerable to lazy mechanics who ground down the shims during a tappet adjustment instead of sourcing the correct size. Any hint of uneven grinding would stop the buckets on top of each valve from rotating every time the cam lobes hit the buckets leading to an extensive and expensive but totally avoidable top end repair.

A sharp 125 is hard to find today but deserves a much higher profile. It really did, through some clever production engineering and economies of scale, preview the priorities of today’s cars. At the same time, it could be immensely satisfying to drive for a model that owed far more to mass-production than others of its kind.

Protect your Fiat. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.