1968-72 Datsun 1600: Much More than a Cut-Price BMW

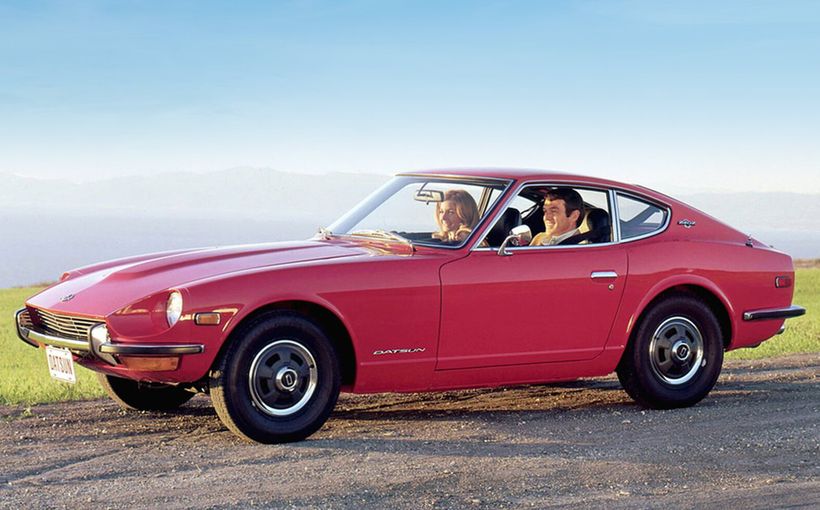

On its February 1968 local release, the Datsun 1600’s specifications matched or bettered BMW then proved more reliable and rugged under local conditions. Despite the full force of Aussie trade barriers, the new Datsun’s $2050 import price was just $5 more than a locally-assembled Cortina 1300. Its performance and on road behaviour shamed the latest Cortina 1600 GT which cost a full 25 per cent more. The Datsun 1600 is rightfully listed globally as a 20th century game changer, with the benefit of hindsight.

The Datsun 1600 was initially met with confusion. Similar to the reaction the HQ Holden generated in 1971, Australians didn’t know how to respond to a car that simply did not add up for a Datsun in 1968. Because Japan had already served-up several new models with extra complexity that didn’t deliver, buyers were justifiably wary.

In 1971, Wheels explained the reaction.

“First, it hit the local scene with a genuinely advanced specification, low price, international (if bland) styling, high performance and five seater room.”

“It offered so much the average family car buyer was sceptical in the face of such genuine value for money. Consequently, the 1600 didn’t take off over night.”

“Initially priced at a staggeringly low $2050, the 1600 was still above the magic $2000 mark, which really meant something in those distant days (four years ago was a long time in the late 1960s automotive scene) – and more important, $70 above the then champ from Japan, the Toyota Corona.”

“But the two cars were never really in the same class. The Datsun’s modern concept provided more room and vastly increased performance. On reflection perhaps the first 1600s were underpriced. Instead of competing in the under $2000 bracket with the Corona, Renault 10 and Morris, it belonged more with the Mazda 1500, Cortina 440 and VW 1600.”

“Cunning motorists soon realised the Datsun – at an in-between price – offered the best of both groups, and slowly the sale impetus towards the 1600 began. Even three price rises and the introduction of new cars designed to compete directly with the Datsun have done little to halt the stampede.”

The final Datsun 1600 Deluxe as assembled in Australia on the same assembly lines as Volkswagen and Volvo. That colour was familiar to Superbug and Type 3 Volkswagen owners from this era.

By early 1970, the Datsun 1600 had joined the Datsun 1200 and a new range of current German Volkswagens on the former VW assembly lines at Clayton, Victoria. Because its price jumped to $2350 at that point, this move was clearly not intended to save money.

Import restrictions had not only inflated the local 1968 Datsun’s import price so it couldn’t make life any tougher for the locals but volume restrictions on imports meant that Datsun could never meet demand. Even while Australians were still making up their minds over the 1600, the new model had turned local Datsun dealers into order takers!

The switch to local assembly allowed new volumes that would encourage dealers to focus on Datsun exclusively with retail prices that could at least be maintained against local opposition. The 1600 would spearhead Nissan’s efforts to become a volume rival for the AMI-assembled Toyota Corona and the new Mitsubishi Galant soon to be built by Chrysler.

Locally assembled Datsun 1600 examples featured durable local Dulon paint in bright new colours shared with Volkswagen and Volvo, and better trim. It also allowed Datsun to offer a local 1600 GL, similar in concept and detail to the local Renault 12 GL, Ford Cortina 440 L and Torana SL.

As soon as the Datsun 1600 proved it was not another Japanese blind alley, it didn’t take long for Australians, right up to senior government level, to question why Australia was still supporting second rate models from US, European and British companies. Derisory comments about Japanese cars were replaced by begrudging admiration and wariness that the Japanese could achieve so much in so little time.

Hillman, BLMC, VW, Renault, British Fords and British-based Toranas would soon be casualties. Even the full-size Holden was not safe as the Datsun 1600 was a compelling case to downsize without losing core Holden virtues. Today’s preference for passenger cars of this size started here, not the Corolla or Datsun 1200 which were much smaller.

The downside was that Datsun would become part of the same tangled social and political machinery that would push new cars further out of reach for Australian buyers. As more and more companies like Datsun were coerced into local assembly with import quota and tariffs as a buffer, the unions and management of the car and component companies were locked into constant battle fighting for a bigger share of the fat margin this created.

By the time the Datsun 1600 left the market in 1972, its price had risen to $2700 and its 180B replacement left little change from $3000 by the end of that year. By 1975, that process and dwindling quality had caused an industry-wide buyer strike. The vested interests which now included Nissan workers and component suppliers pressured the Whitlam government to cut sales tax to get sales moving again.

The Datsun 1600 which had earlier exposed the folly of Australia’s overprotected industry had become a victim as Nissan had to later delete some of the 1600’s stand apart engineering content in later models including the very last local Skyline built until the 1990s.

As soon as the Datsun 1600 arrived in 1968, it might have been more useful had a better informed Aussie public seen it as a yardstick against which local policies could be judged. The Japanese industry had delivered the sophisticated 1600 in a shorter time frame than was available to the Australians. This is how they did it.

From Austin A40 to Cedric and Bluebird

Just as Australia Inc was building its future on General Motors technology after 1945 so it could leapfrog where it was in 1939 before World War II, Nissan elected to go with Austin after 1951. Nissan built the Austin A40 Somerset before introducing the A50 Cambridge. Australian engineers had been building similar Austins including several unique versions in local factories for some time.

By any measurement, the Australian industry was at least six years ahead of the Japanese industry. Local component and assembly quality for most of the 1950s was up there with the best in the world.

This might explain the totally different behaviour of the engineers from Commonwealth Austin outposts such as Australia compared to the Nissan crew at the numerous training sessions held at Austin headquarters in Longbridge, UK.

According to consistent reports from those who were there, the Antipodean engineers saw these sessions as an interruption to a good time paid for by their British masters. The Japanese treated them as an opportunity to learn every Austin process and improve on it. With the future of the Japanese nation in their hands, their progress was staggering.

The Japanese had agreed to a deal that only allowed them to sell Nissan-built Austins on the Japanese market and thus could not compete with Austins from other sources. However, if Nissan used its Austin engines and other parts in its own models, they would not be subject to those restrictions. This was the critical self-advancement clause missing in Australian consciousness.

The Japanese-built A40 Somerset took over in 1953, after the British version was withdrawn in 1952. These early cars were assembled entirely from imported British parts, something that even Australia was no longer dependent on for its local British cars or Holden.

By the end of 1954, the A40 was replaced by the A50 Cambridge, a stylish new model that added the new 1.5-litre B-series engine as an alternative to the 1.2 litre of the old A40. This effectively gave Nissan a choice of two engine ranges for their own Nissan model ranges. In just three years, not a single component had to be imported to build the Austin A50. By the end of 1957, Austin had to concede that the Japanese A50 was better than the Longbridge model.

Because both the A40 and A50 engines were critical to Nissan’s future and were already powering commercial vehicles of Nissan design, Nissan invested in the services of the American engineer Donald Stone to rid the Austin engine of its frailties and faults, including chronic oil leaks. Just as Austin’s B-series evolved into engines up to 1.8-litres, the new Nissan engines included a 1200 to transform its small and crude Bluebird range and a larger 1900 series for the first Nissan Cedric.

These engines were so successful that a direct descendant of Stone’s 1200 would continue to power the 120Y/Sunny series into the 1980s with exceptional economy and longevity. Various pushrod six cylinder engines from the same period would power Nissan trucks and four wheel drives for almost the same period. The 1200 Stone engines and the Datsuns they powered still form the transport backbone of some of the poorest African nations.

The bottom line was that Austin had become irrelevant to Nissan by early 1960. The larger, more powerful Nissan Cedric (available as a 1500 and 1900) made the Austin A60 Cambridge as sold in Australia redundant. A vastly improved Datsun Bluebird 1200 was now ready for export as an entry level small family car, similar to the original A40 Devon.

Both model ranges were previewed in Australia with the Datsun Bluebird going on sale in 1961 as a fully-equipped 1200 four door sedan for $2096. The Nissan Cedric followed as a 1900 in 1963 as a $2500 Holden rival. Both cars shocked Australian reviewers who couldn’t believe how good they were and how far Nissan had come.

It was only in 1958 that Nissan was in Australia, rallying a team of Bluebirds in the Mobilgas Round Australia Trial. Despite a first in class and a fourth overall, the little car’s crude light truck full chassis construction with beam axles front and rear left everyone in Australia feeling secure.

However, the Datsun team was led by the visionary Yutaka Katayama who had noted the Japanese accolades that came Toyota’s way following a similar effort in Australia the year before. Mr K would rise to prominence again after the Australian experience helped shape his motor sport ambitions and defined the car he really wanted.

Nissan’s 1958 Trial assault also brought the little Bluebird to the attention of Sir Laurence Hartnett. It was Hartnett, always on the lookout for the right car to challenge his former GM employers, who launched the first Datsuns in Australia.

To grasp how the Datsun 1600 could emerge as advanced as it was as for a 1967 Japanese release, it is worth tracking where Nissan was in 1960 compared to those Australians still backing the Austin path (and Holden which was still recycling its 1948 design).

To avoid confusion, Nissan was always the parent company, Datsun was the name on the cars. During these earlier days, the Nissan name was sometimes applied to the more expensive models. The Datsun badge was found on the cheaper cars. The Nissan badge was then phased out altogether in Australia on passenger cars following the first generation Cedric and the special bodied Silvia. Nissan returned as the sole badge during the 1980s.

In 1960, the Australian Austin (BMC) team were still offering a re-bodied Austin A50/55 with a Farina restyle at which point the first Nissan Cedric was a better fit for Australian tastes. After being told by the Brits that stretching the B-series engine to 1.6-litres was impossible, the local BMC team did it anyway and created the A60 Cambridge several years ahead of the UK market. Despite these local efforts, the A60’s 55bhp (compared to the Nissan Cedric 1900’s 95bhp) was never treated seriously against its Holden opposition. The Australian 85bhp six cylinder Freeway version that followed in 1962 could only hold the line for a year.

As for the 1960-61 Datsun Bluebird 1200 market entry, the Australians were building the worthy Austin Lancer/Morris Major, a local version of an abandoned mid-1950s Morris Minor replacement. The Lancer at least had the A50’s larger B-series 1500 engine but in the old Austin specification its 50bhp could never take the fight to the 1961 Bluebird’s re-engineered 1200 with its 60bhp. More than any other Nissan model, the rugged, full-chassis but relatively quick Bluebird showed how relevant Nissan could become to the Australian market.

Modern Motor’s tester Bryan Hanrahan tested the local Lancer/Major 1500 and Datsun Bluebird 1200 within 18 months of each other and found the Bluebird significantly faster (80mph vs 76mph) and quicker in every acceleration increment. Although the Bluebird had a three speed column shift, its shift quality and synchromesh on all forward gears gave it an advantage over the Lancer’s baulky four speed floor shift and non-synchro first that could not be accessed on the move. The most telling figure was the Lancer’s 0-60mph of 27.4 seconds versus the Bluebird’s 17.8!

The alarm bells should have been ringing by 1961 after a Japanese 1200 could run away from an Australian 1500 and give away nothing in the ruggedness stakes. Nissan styling had also become more mainstream as global trends were integrated and key Farina details provided continuity in the Austin changeover. In terms of looks, there was little between the local Lancer and the latest Datsun Bluebird.

In 1961, both Holden and the local BMC arm had the edge in unitary construction, local design and engineering capabilities and component supply. Both could have still outpaced the Japanese industry if the will was there.

Then Nissan handed the entire design task over to PininFarina at a time when BMC was handing over half-finished models to the Italians to clean up.

By the mid-1960s, Nissan had created a consistent internal design signature that was the equal of the best Western automotive companies. The Farina-styled Datsun 1300 (the latest rebadged 410 Bluebird) and 2000 (the latest rebadged Nissan Cedric) were commanding mainstream consideration by 1966. The Datsun 1600/Fairlady Sports and Nissan Silvia were also credibility builders missing from Australian manufacturers.

Datsuns were now on the shopping lists of more Australians. Yet these beautifully-styled Datsuns were still missing an engineering edge as their Austin origins were never far away under the bonnet.

The real progress was happening elsewhere.

Prince Transforms Commoners into Royalty

Nissan’s acquisition of the ailing Prince company was a shrewd one. As an elite former aviation company, Prince had re-invented itself in peace time as an aloof motor company that befitted its relationship with Japanese royalty. It courted big Western names in its quest to deliver the best and most advanced in Japan.

Its preferred styling house was Michelotti, a relationship which explains why the Prince Skyline and Gloria models looked more modern and exciting against the quaint generic looks of contemporary Toyotas and Nissans. Prince also shadowed Mercedes-Benz in developing a single overhead cam six cylinder engine for its new Gloria flagship. Certain details (such as carburettor and exhaust placement) were changed so it couldn’t be labelled an exact copy yet the German engineering influence was obvious.

For the all new Skyline 1500 that now sat below the Gloria, Prince had developed an advanced pushrod 1500 engine with 73bhp, a benchmark for this class but only until the new shovel-nosed Toyota Corona 1500 claimed 74bhp months later.

Despite tiny local sales, both the Prince Skyline and Gloria were seen as wake-up calls in Australia as they represented the most visible (and ominous) signs of the massive progress being made in Japan. For 1964, the Prince Skyline GT with its triple Weber 40mm carbs, 5 speed close-ratio gearbox, long distance tank, full instruments and sports steering wheel, limited slip diff and long nose, short tail styling was gob-smacking.

Sadly, Prince hadn’t put the same effort into the marketing and distribution side of the business. By May 1965, a Prince merger with Nissan was announced for completion by the start of 1966.

The elite engineering and the innovative new Prince models on the drawing board were exactly what Nissan needed to leave behind its basic Austin roots and move to the next level. The first visible outcome of this merger was the new and amazing L20 overhead cam in-line six cylinder Prince engine already under development before the merger. It appeared in a special version of the second generation Nissan Cedric or the Datsun 2000 as it was known in Australia.

Known as the Cedric Special Six, this elite Cedric kept the new engine close to home and was not related to the Austin-inspired pushrod 2-litre six that appeared in Australian Datsun 2000 deliveries. Depending on who is doing the talking, the L20 was an amazing new engine benchmark or one dogged by teething troubles. Yet its 123bhp versus the 109bhp of the pushrod Datsun 2000 highlighted the gains available by going down this track.

In a similar but unrelated development at this point, Prince engineers also fitted a Mercedes-style overhead cam head to a 2-litre long stroke version of the Austin-inspired 1600 pushrod engine in the Datsun Fairlady. The Datsun 2000 Sports, as it was called in Australia, set new performance standards after the new engine delivered an even 150bhp (the same as Triumph’s hot new fuel injected six in the TR5 sports car) mated to a five speed gearbox. Because this was nearly double the MGB’s output, which had been static for five years, this final version of the full-chassis Fairlady roadster became a popular motorsport choice in both the US and Australia.

But there was more to the Cedric Special Six than the L20 engine which was of relevance to the Datsun 1600. It came with bucket seats, distinctive front and rear styling and full wheel trims. Based on the same Farina style as other Cedrics, it established Nissan’s own design cues for a premium model including a horizontally divided grille and horizontal tail lights. If it had come after the Datsun 1600, it would have been described as a full-size 1600.

Various sources claim that the L16 SOHC engine which first appeared in the Datsun 1600 was either a 1.6-litre version of the new Datsun 2000 Sports engine or the Cedric Special Six minus two cylinders. Neither was the case as the Datsun 2000 Sports engine block was based on the heavy duty 2-litre pushrod four fitted to various Nissan commercials. In later five-bearing form, it was much tougher and more expensive to build than required for the Datsun 1600.

And even if the L16 was a development of the L20 in principle, it was an entirely new engine as its different bore and stroke confirmed, while incorporating all the lessons learned from the Cedric Special Six and the Datsun 2000 Sports engines. It was the L16 that had two cylinders added to create the L24 for the later Nissan Cedrics/Datsun 2400/240K and 240Z sports car, not the other way round.

It should be noted that the L16 retained the same cylinder head configuration as the original Mercedes-Benz engines with both the carburettor and exhaust on the same side but like the Prince, opposite to the Mercedes-Benz, probably for RHD. Final development was completed by Yamaha. Its inlet and exhaust manifold locations also matched Nissan’s earlier Austin-based engines which were often fitted to the same Datsun model depending on market.

While the L16 was being finalised by Yamaha for the new Datsun 1600, Prince engineers had moved on and developed a cross-flow SOHC engine for the Nissan Laurel (a model not seen in Australia that rivalled the Corona Mk II) which looked exactly like a Datsun 1600 only bigger. This crossflow 1.8 was a gem and delivered 105bhp before it was upped to 2-litres. It was later replaced by the L-series fours and sixes after they had become more reliable and cheaper to build.

The official Datsun 1600 output was 96bhp just after the EH/HD’s 149 set the 100bhp benchmark for an entry Holden. The ever popular MGB in 1968 boasted 95bhp and the hot new Mazda1500SS with a 30 per cent price premium offered just 86bhp despite twin carburettors.

The Prince’s job was complete!

The German Count Who Created Silvia

It has taken Nissan an age to even admit the existence of Count Albrecht Graf Goertz in Nissan history. Several Japanese companies never openly admitted to collaborations with German or Italian companies or took up invitations for joint ventures. Under post-World War II tensions, it would have been seen as provocative if former enemies collaborated on anything.

Because Goertz worked for the Americans as well as the Germans, he was on the verge of acceptable but no risks were taken on publicising his involvement at the time. Goertz may have been responsible for the sublime BMW 507 roadster but he also designed the first Nissan Silvia, a handbuilt coupe that sold only in tiny numbers in Japan, New Guinea and Australia. This boutique model, built on the 1500/1600 Fairlady chassis, was a stunner. It was widely believed that it came from Bertone like the Mazda 1500 as they looked similar and surfaced at the same time.

As is so often the case, fact can be stranger than fiction. According to several sources, Goertz introduced Nissan to clay model techniques and the idea of designing a new model as a new, complete and separate entity, not a patchwork of generic styling trends. He has since been acknowledged as having major input in the Datsun 240Z. But his first Nissan design, created while introducing Japanese designers to this more holistic approach, was the Silvia.

Even if the resemblance between the Silvia and the Datsun 1600 was minimal, they did have something in common. Both were very early products of this new in-house design process. Neither was dependent on any Italian design and there were consistencies such as the 1600 capacity, quad headlights, horizontal full width grille and similar tail light design.

It is often assumed that the Datsun 1600 was the Farina sequel to the previous Bluebird 410/411 but it was in fact the product of Teruo Uchino who had been with Nissan since 1963. He was very much aware of the convergence of stying influences within Nissan including Pininfarina, Goertz and Michelotti at Prince. This was a critical distinction as the Datsun 1600 would replace the Prince Skyline 1500 in several markets including Australia.

As a top shelf four cylinder model, the 1600 featured slightly-raised eyebrows to link it with the premium Cedric range (and its strong Farina looks). The tail light panel with the horizontal tail lights defining its outer edges was also a premium Nissan theme. Contrary to ill-informed commentary at the time, the design owed nothing to the BMW range.

It did however integrate the 410’s full length side recess, a Pininfarina touch since dubbed inside Nissan as the “supersonic line” that had first appeared on the 1961 Cadillac Jacqueline concept car.

And while the Uchino design was a timeless, if slightly understated design, it would have been just another generic Japanese car if it wasn’t for the influence of a Nissan executive who had cut his teeth in the wilds of Australia. That man was now the CEO of Nissan US, the hard-working and persuasive Yutaka Katayama or Mr K.

The Irrepressible Mr K

By 1966, Mr Katayama could see how the engineering-led compact BMW models were dramatically changing US expectations for a small car. As the head of Nissan US, he would personally deliver cars to customers and his dealers and listened to the feedback. He looked at the stylish but antiquated Austin-derived models that Nissan was fielding and figured there was no time to be wasted if Nissan was going to be a player in this new direction.

He had also learnt from his days in Australia how effective the early Bluebird’s success in the 1958 Mobilgas Trial was in changing the perception around small Japanese cars. Competition was very much in the back of Mr K’s mind as he lobbied his Japanese colleagues into supporting a massive transfusion of engineering into the 510 replacement for the 410 Bluebird.

Nissan’s engine and styling capabilities had already been lifted to a new level and were ready for action but the chassis design was the next big hurdle. The new car had to be a tough but relatively light unitary structure. It took engineer Kazumi Yotsumoto to read between the lines of what Katayama was wanting. He took it as a personal challenge to make the new 510 Bluebird a car that would be an extension of the driver. This was a new way of thinking for Japan in 1966.

Yotsumoto’s team delivered an unusually light and tough chassis-less structure suspended at the rear by a semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension with double-jointed driveshafts. This design was seen globally as the next step forward over the swing-axle rear ends under Volkswagens, Renaults and the discredited early Chevrolet Corvair.

It did not have the level of camber or toe control of a full double wishbone design like Jaguar’s but for a space efficient sedan, it remained the bench mark suspension design until BMW added an extra control link to its semi-trailing IRS in the early 1980s. It must be said that the Datsun 1600’s rear end was identical to what was under IRS Commodores from 1991 to 2001 after Holden deleted the BMW-inspired extra control link that Opel added to its V-cars in 1987.

A stronger than usual MacPherson strut front end and standard front disc brakes highlighted the integrity in the Datsun 1600 design. In hindsight, the steering might have been better if it was rack and pinion (as the Prince engineers had specified for the lookalike Laurel) and not recirculating ball.

However, the 1600’s primary focus was an urban runabout for the US and an all roads small family car for Australia and equally tough markets in Africa and Asia. As far more prestigious manufacturers discovered in the days before universal power steering, recirculating ball steering was a good compromise between low effort and isolation of road shock.

The Australian brochure for the 1969 model positioned the Datsun 1600 as a premium family car with extra room for full-sized Australians. Local Datsun importers had little choice as local industry protection added at least 25 per cent to the price over the US models.This early cabin design verifies that the Datsun 1600 was not a BMW copy or challenger but a measured attempt to offer similar engineering to budget buyers, an approach soon embraced by the entire Japanese industry.

It is well-documented that Australian requirements were as important to the Datsun 1600 as Mr K’s demands for the US. Boot size and ground clearance were two such considerations. Yet the big step forward was designing the cabin around an average Australian male, not the much smaller Japanese average.

For the record, Nissan’s Australian office defined this Australian as 5ft 10in with a weight of 11.5 to 12 stone (178cm/76kg). It allowed the 1600 to take the battle to the Morris 1100, Ford Cortina Mk II and the Hillman Hunter, all of which had stretched cabins to reflect the higher living standards and growth spurt that occurred in Western populations after World War II. Although cabin space was by no means generous in the 1600, it was a quantum leap over previous Japanese small cars which were almost uninhabitable in the back seat.

The flow-through ventilation with dash outlets combined with the more common centre air vent in early cars were also an important advance for Australia.

Not surprisingly, Mr K was ecstatic when the first Datsun 510 reached the US as were the Australian importers.

What Happened Next

The first Datsun 1600 was a rushed job albeit a very good one. You can pick the 1968 model by the plain centre horizontal grille bar, the old school “clap hand” wiper pattern and the larger, almost rectangular, tail lights divided into three vertical sections. The instrument panel featured a plain rectangular speedo.

The 1969 model was heavily upgraded with many parts not interchangeable. The obvious changes were a new grille with Nissan’s prestige centre badge added and a modern wiper pattern. Yet most of the lights, steering and suspension parts, seats, door internals and other bits like the bonnet support structure were all upgraded. The rear looked much cleaner with slender tail lights in trapezoidal chrome frames.

By February 1970, the 1600 was in local production with a cleaner matt-black grille, a moulded plastic dash with round instruments with a space for tacho or clock and extra chrome detailing in the tail lights that gave the rear a slightly sleeker appearance. The distinctive full wheelcovers (they looked similar to the XR Fairmont’s) remained unchanged. The rubber-tipped bumper overriders had been deleted since the 1968 model but made a re-appearance on the wagon first introduced in Australia in April 1971.

The Borg-Warner 35 automatic option did not arrive until March 1970 and even then with a column selector only. It was a popular choice as the engine had the grunt to offset any power losses. These automatic versions are the main source of unmolested, mint survivors as they were usually babied compared to the manual models.

Just after the wagon version which was badged as a GL, a local GL sedan arrived in May 1971 with radio, clock and other cabin tweaks. It had distinctive local full wheel covers (similar to the Cortina Mk II L and various AMI models) and a full length chrome side strip.

Although the 1600 continued in other markets still at the top of its game until 1973, it was replaced by the 610 or 180B in Australia by October 1972 under the impression that it was past its use-by date. An appalling short cut in local testing helped generate that impression.

Wheels magazine had been bombarded with requests for copies of its March 1968 Datsun 1600 road test, so much so, the magazine undertook a four car comparison in February 1971. This mega-test pitched the latest Toyota Corona 1500, Mazda Capella 1600, Mitsubishi Galant 1300 against the latest locally assembled Datsun 1600 and suggested “the Capella and Galant go harder, the Corona, Capella and Galant all have more modern styling, better fittings and more comfort, and the Corona at least is more economical.”

Although Wheels conceded that none of these would see which way the Datsun 1600 went on a winding or dirt road, the overwhelming impression was that the model was past its use-by date. It was almost as if the comparison had been written from the latest cars’ on-paper specifications, which could be notoriously inflated for Japanese imports.

Anyone who had driven all of these cars at the time (as this writer had) would know the Wheels comparison and its conclusions were wrong.

A close inspection of the February 1971 comparison panel will reveal that all the Datsun 1600 test figures came from the March 1968 test. The 1968 car was straight off the boat and like most Japanese imports at the time would have needed re-tuning for local fuel as it was better than what was available in Japan. Typically, a Japanese import needed leaner jets and more advanced ignition settings after which performance and economy would dramatically improve.

This would explain why a new Wheels Datsun 1600 test only months later after the comparison in 1971 (with identical on paper specifications to the 1968 car) posted a top speed of 96mph (154km/h) versus 91mph of the 1968 car. Its 1971 standing quarter mile time of 18.3 seconds was a full second ahead of the 1968 car. The 1968 30-50mph of 11.6 seconds which condemned the Datsun 1600 to last place in the 1971 comparo by a significant margin took just 6.5 or 10 seconds in the 1971 test car depending on gear.

The 1971 test left the Datsun 1600 only slightly slower than the Capella in top speed making it second on that criterion but slightly faster than the Capella over the standing quarter which made it number one on that score. The Datsun 1600 was still not only the quickest in every performance increment in 1971 except top speed (there was only a few mph in it), it was still better in all areas on the road especially as soon as the black top ended.

Wheels had the opportunity to correct all this in its later 1971 Datsun 1600 test but chose not to. Only those with a copy of both 1971 Wheels issues could join the dots.

The Datsun 1600 in fact went out on a high in Australia as it did everywhere else. Yet the Datsun 610/180B was the right replacement for the 1600 at the right time in Australia despite widespread US and UK commentary that continues to dismiss the 180B as an unworthy successor. The 180B’s new styling dovetailed nicely with the latest Australian family cars and its extra power and proven Datsun 1600 engineering made it a realistic alternative after the first fuel crisis hit. But that’s another story.